With thousands of hectares ablaze with bush-fires across the country, and temperatures topping 40 degrees Celsius in many regions week, including Sydney, the extremes of our environmental and climate crisis are omni- and ominously present, reinforcing the resounding message that we cannot sustain our current energy-hungry lifestyles.

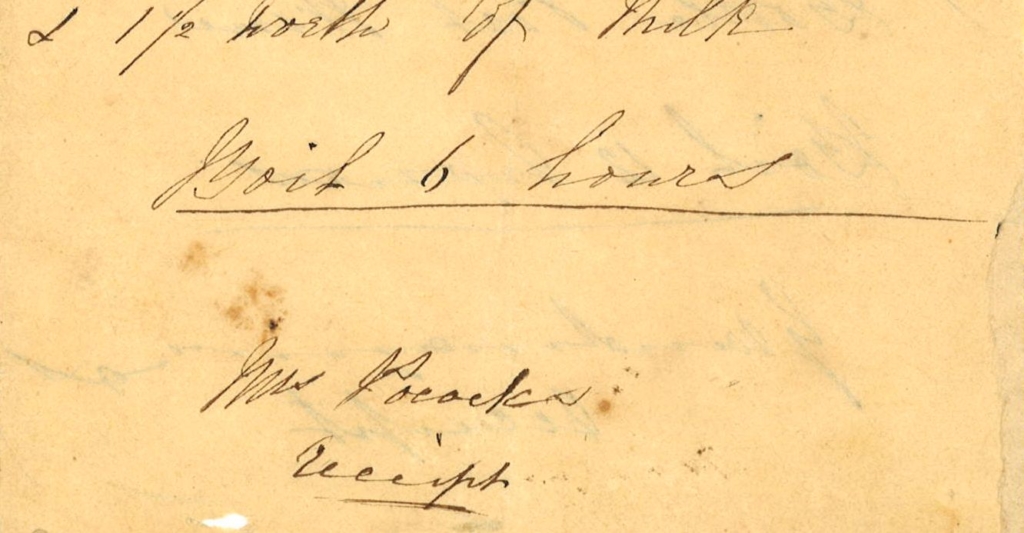

The full selection of ‘receipts’ from this collection can be found here

Energy conscious

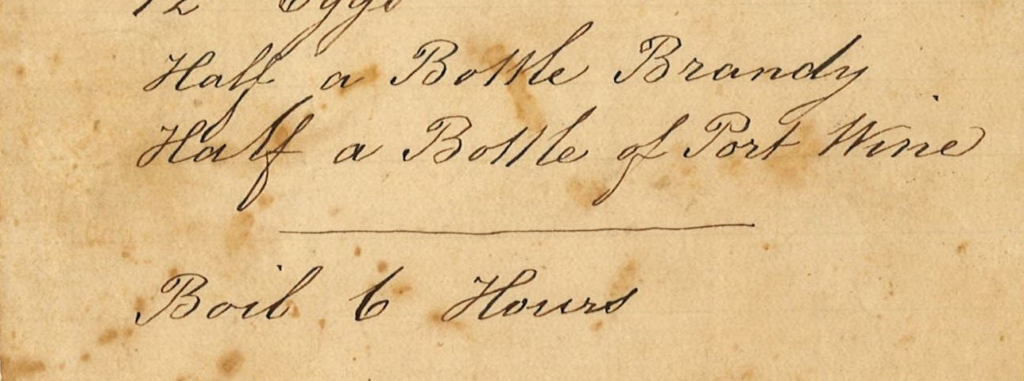

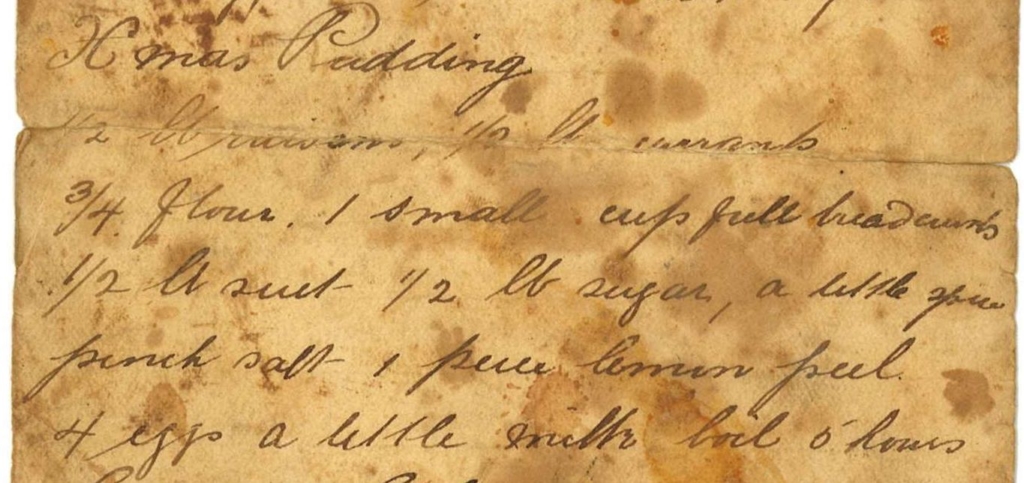

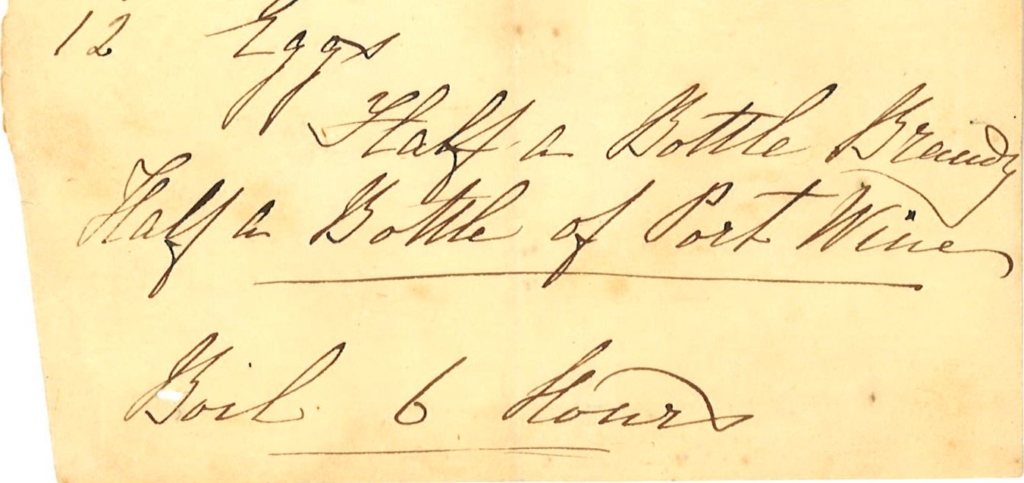

I’ve been embroiled in Christmas pudding making these last few days, giving me plenty of time as they boil for six hours – the minimum time required to achieve the rich dark colour we expect from a good plum pudding, as per the recipe below – to ponder the value and usefulness of working with food heritage in context of environmental responsibility.

Indeed, having a pot on the stove for six hours, especially in summertime seems a ridiculous waste of energy, but on closer consideration, the traditional plum pudding has its merits in terms of energy use.

The full selection of ‘receipts’ from this collection can be found here

Eating local

Firstly, the primary ingredient, dried fruit, does not require refrigeration, a very big plus. Our fridges have a lot to answer for – they are one of the highest consumers of energy in our homes, not to mention large-scale cold-chain food systems, but we’ll revisit that hot potato another time. Australia produces high quality dried fruit – sultanas, raisins, currants and citrus peel – eliminating the need for transnational shipping (when buying your fruit, check the country of origin and buy locally grown product). Admittedly these are introduced plants that need irrigation and some mechanised processing is involved in readying them for market – perhaps one day we will be enjoying dried quandong and lily pillies in our puddings. The concentrated sugars in dried fruit also provide natural sweetness. My preferred Christmas pudding – based on a Mrs Beeton recipe from The book of household management, 1861, deemed ‘Very good’ – contains no sugar, avoiding the need for highly refined cane-sugar.

The full selection of ‘receipts’ from this collection can be found here

Grating edge

In this recipe, breadcrumbs are used rather than flour. Apart from creating a light and moist texture, the crumbs make good use of stale bread. Bread had to be grated to turn it into crumbs ‘back in the day’; a food processor makes this a job done in seconds, a reminder of how much convenience we enjoy from bench-top appliances – but the option is there if you want to minimise the use of electrical power.

The full selection of ‘receipts’ from this collection can be found here

The remaining fresh ingredients are eggs, which when home-raised and fed on kitchen scraps or purchased from small producers are an eco-friendly option over store-bought eggs, and suet (a particularly clean type of beef fat) was sourced from the butcher as required. I lose points here, as I choose to use butter instead of suet, for a lighter flavor and textural quality, and concede that this requires refrigeration, in fact I freeze it so that it can be grated the way suet would have been.

Festive indulgences

Brandy and spices, which add festive spirit to the pudding, are both the product of ‘natural’ preservation processes – the former made from fermented grapes and distilled, and the latter, generally dried. Kept airtight, away from light and heat, they keep for years, without refrigeration.

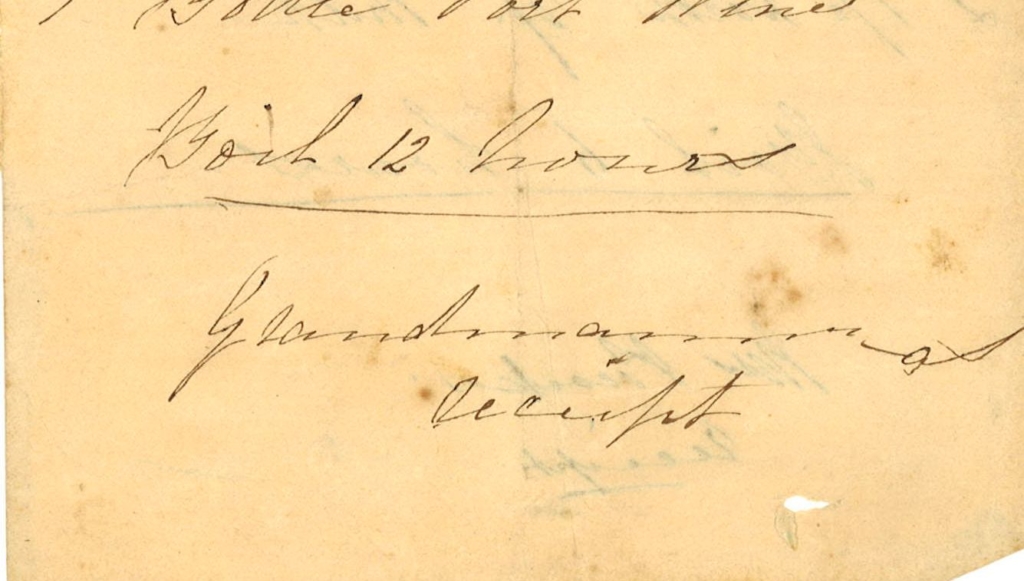

“Boil 6 hours” – or 12!!!

And now the thorny issue of the cooking process – the requisite boiling for six hours, which seems excessive and wasteful in terms of energy consumption. But boiling a pudding is far more energy-efficient than baking a cake, for example, which requires an oven to maintain a high temperature for up to an hour, perhaps more for a large fruit cake. The plum pudding, however, can be cooked on a stove top, with direct heat rather than ambient heat. And if the pot in which the pudding is immersed has a tight-fitting lid and is of relative to the size of the pudding bowl, it uses very little water; once it has reached boiling point, only a small gas flame or medium setting for an electric hob is required to keep the water at a steady simmer.

The full selection of ‘receipts’ from this collection can be found here

And the feast goes on

Best of all, leftover pudding will keep without refrigeration for several weeks – perhaps months – if stored in an airtight container kept in a cool, dry, well ventilated pantry, leaving space in the fridge for the more perishable festive fare. And the pudding bowl and cloth can be used over and over again.

To view the full ‘receipts’ from the featured manuscript collection click here

Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection MSS 2011/1 [Ann Weaver], © Sydney Living Museums