This week we welcome guest author Dr. Madeline Shanahan to the blog. A historian and archaeologist, Madeline was a guest speaker at this year’s Spring Harvest festival at Elizabeth Farm, where she talked with Jacqui about spices. Earlier this year her new book – Christmas Food and Feasting – was published, looking at how the concept of the ‘Christmas dinner’ evolved, both in Britain and throughout the English-speaking world. So pull up a crate of mangoes and carve up the pudding as we dive in! [Eccentric images supplied by yours truly]

Nostalgia, memory, romance and ritual…

As ‘Stir-up Sunday’ – the traditional day for preparing Christmas puddings – has just been and gone many Australian families will have taken to their kitchens to prepare the annual Yuletide feast. Having just experienced one of the hottest Novembers on record though, as hot steam filled the kitchen more than one of us has probably questioned our choice of offering. Every year many Australians still cook a traditional roast and pudding, and each year commentators will question our choice of festive fare. Ultimately, Christmas is a festival characterized by nostalgia, memory, romance and ritual, and so there are some traditions that are faithfully kept each year in the face of all reason.

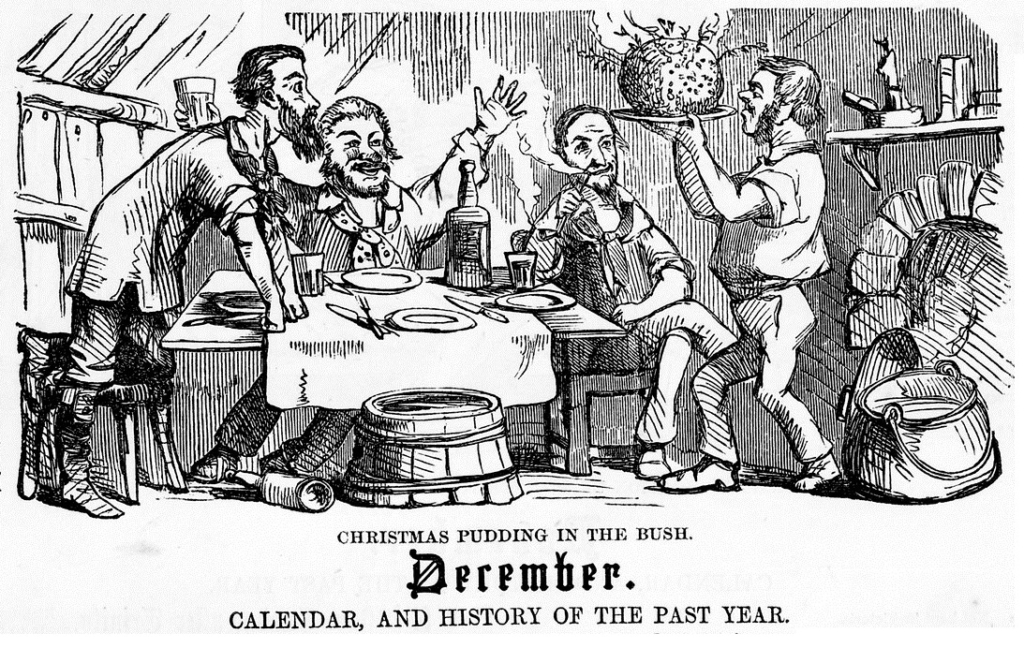

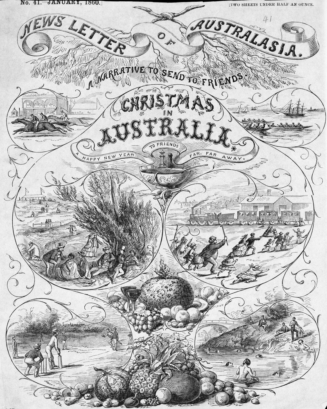

Even at an early date though, the peculiarity of preparing a hot meal in a sweltering Summer was amusing to colonials. Its absurdity came to represent part of the incongruity and ambiguity of Antipodean identity at the time. Christmas in high Summer made as much sense as a land at the bottom of the earth with black swans and platypus. This was, quite simply to European eyes, a land of upside downs in which these newcomers were yet to feel at home; no longer British, but not quite Australian either.

Reaction to the pudding in particular ranged from faith adherence, to wry amusement, to outright condemnation. Journalist and novelist Marcus Clarke, most famous for his book For the Term of His Natural Life (1874), took particular issue with the Australian adoption of the Christmas pudding in his famous quote:

A very merry Christmas, with the roast beef in a violent perspiration, and the thermometer at 110° in the shade! . . . It may be a rank heresy but I deliberately affirm that Christmas in Australia is a gigantic mistake . . . if the gentleman in question is sensible, and possesses digestive organs, it is quite probable that he will refuse to load his stomach with the portable nightmare known as plum pudding.

Marcus Clarke, Australasian, 26 December 1868 [1]

The great Australian poet Henry Lawson also shared Clarke’s views and detested plum pudding, describing it as “the most barbarous institution of the British” [from “The Ghosts of Many Christmases” in The Romance of the Swag, 1907]. His sentiments are summed up in the description of Christmas dinner in his 1907 collection of short stories Send Round the Hat:

“We had dinner at Billy Wood’s place, and a sensible Christmas dinner it was – everything cold, except the vegetables, with the hose going on the veranda in spite of the by-laws, and Billy’s wife and her sister, fresh and cool-looking and jolly, instead of being hot and brown and cross like most Australian women who roast themselves over a blazing fire in a hot kitchen on a broiling day, all the morning, to cook scalding plum pudding and red-hot roasts, for no other reason than that their grandmothers used to cook hot Christmas dinners in England.”

“That pretty girl in the army,” in Send round the hat, 1907

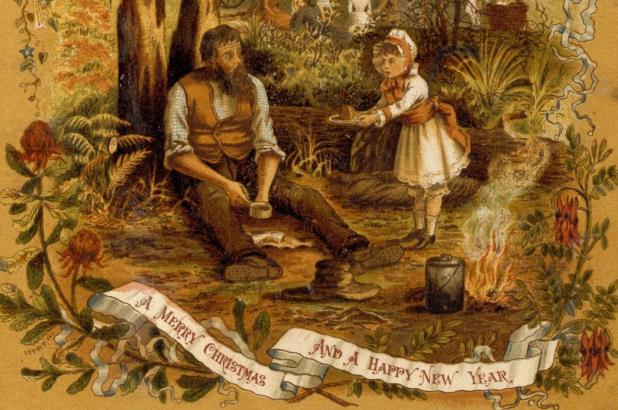

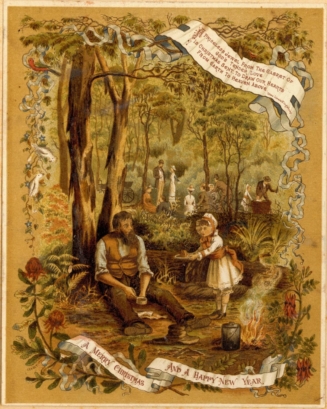

This debate about Australia’s summertime festive fare focused especially on the iconic plum pudding; the ultimate symbol of Christmas and indeed ‘British-ness’ throughout the Empire. Even when colonials began to embrace their climate by hosting festive outdoor picnics, the pudding remained central. In many ways it became even more important, as a sort of linking piece; its presence on the picnic rug helping to legitimize and bring a touch of tradition to this otherwise this unorthodox alfresco affair. This 1881 Christmas card shows a child offering a plate of pudding to a solitary swagman, while her genteel family picnics in the background:

It was not long before there were calls for innovation and a menu that was more seasonally appropriate. Scottish pastoralist John Hunter Kerr championed change, but recognized that the very deep-seated cultural connection to the pudding would be hard to shift:

“It would be a desirable innovation could the hot and heavy plum pudding of the United Kingdom be replaced by some cooler and more seasonable dainty dish but long cherished associations cast a glamour over the luscious compound with its blue ghostly flame which will not readily be effaced.”

John Hunter Kerr, Glimpses of Life in Victoria: by a resident (Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1872), p395.

Take one meringue…

However change we did, and while the traditional pudding remains popular, and a non-negotiable part of Christmas for many, it is no longer unchallenged. New, more seasonally appropriate dishes have entered the menu and been embraced by many. Pavlova is undoubtedly the most common of these; it is decorative, loved by all, seasonally appropriate and quintessentially Antipodean – with both Australian and New Zealand laying claim to its invention in the late 1920s [3]. Regardless of which side of the Tasman can lay rightful claim, by the 1940s Pavlova had started to be promoted as a suitable Christmas offering. Women’s magazines, newspapers, cookbooks and advertising campaigns emphasized that it was more seasonally appropriate than pudding, and as its increasing status as an Antipodean food icon meant that it could even rival the pudding in the identity stakes. Like a pudding, it also makes the perfect grand festive centerpiece on the table, one may be topped with holly and lit ablaze, while the other proudly puts our colourful seasonal fruits such as cherries, mangoes, peaches, passionfruit and berries on display.

Enter, stage left, the Christmas mango!

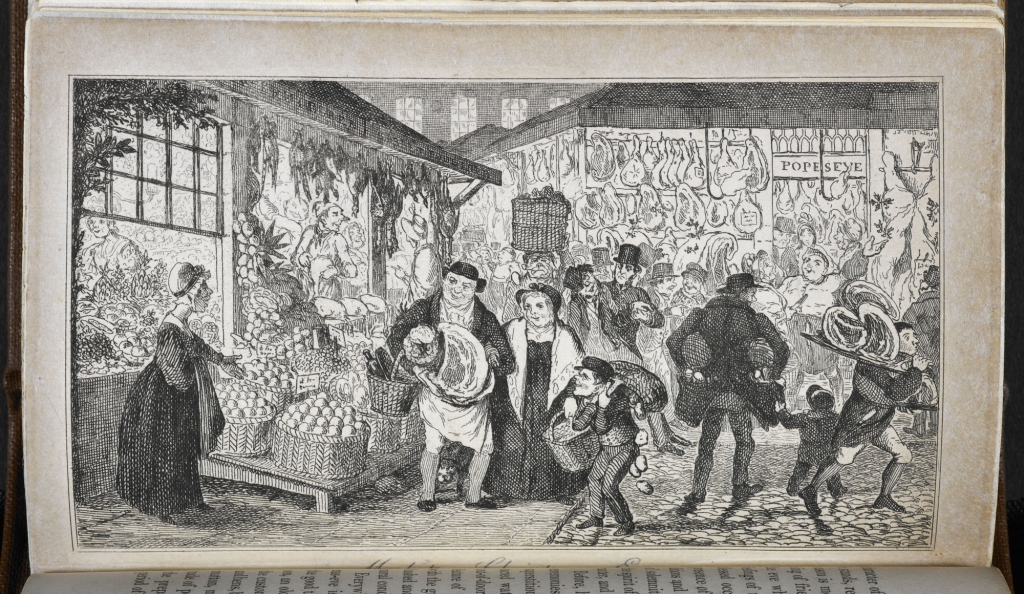

From the late nineteenth century on, long before the invention of the Pavlova in the 1920s, these fruits, but especially mangoes, developed an increasingly significant role in the Australian Christmas. Whereas the other great modern Australian Christmas culinary tradition, the seafood barbeque, is a later twentieth-century innovation, the emphasis on tropical fruits dates right back to the nineteenth century. Colonial newspapers included descriptions of dazzling displays of fruit and native flowers such as Christmas bush. These would be laid out in abundance in the arcades and markets of Sydney, signaling to excited children that Christmas was on its way. Just as English families gathered on the streets of London to marvel at the festive window displays in shops and confectioners, Australians would make an annual pilgrimage to see this cornucopia laid out as Christmas approached. This description of the King-Street Arcade on Christmas Eve in 1890 paints a vivid picture:

The King-street Arcade was a favourite resort, with its great masses of beautiful flowers at the florists and the magnificent spread of fruit near by— the piles of oranges, lemons, mangoes, pineapples apricots, nectarines, peaches, plums, cherries, red and white currants, grapes, gooseberries and other fruits— decked with Christmas bush making a picture worth travelling to see. Flags and Chinese lanterns hung right through the arcade, with every shop making its bravest display…Every shop proprietor made some effort at decoration and display. Grocers, fruit, toy and fancy shops were the most conspicuous, and some of them were to the juveniles nothing more or less than real sections of fairyland. The fruit markets were a sight worth seeing…there were stacks upon stacks of cases; of all kinds of fruit and the stalls were piled high with every variety.”

“Christmas Eve,” The Daily Telegraph, 25 December, 1890, 4.

Newspapers also reported on the fluctuating fruit market, demonstrating the growing demand for tropical fruits, and watching the fruit market became something of a Christmas sport for media commentators, and one that continues to today. A last-minute turn in the weather could destroy the crop and send prices rocketing. One report in the Queenslander (13th February, 1886) complained of the poor quality of “stringy” mangoes in the Brisbane markets over Christmas. An article from 22nd December 1910 warned that shoppers should expect to pay high prices for fruit on Christmas Eve as a gale had destroyed the “Christmas peaches” and “choice fruit of all kinds” – with mangoes from Queensland being the only survivors. [3]

The celebration of fruit at Christmas was not entirely novel, and was a well-established part of Christmas in colder climes. Dried fruits appeared in dishes such as plum pottage (later pudding), mince pies and both Twelfth Night and Christmas cakes. In the medieval world dried fruits were expensive luxury goods imported from the east, which added sweetness at a time when sugar was also rare, and so their use in pottages and baked goods at Christmas marked these dishes out as being celebratory fare, suitable for such a feast. Oranges, satsumas (mandarins), apples and nuts had also long played an important role in the British Christmas, and in the Victorian period would often appear in the stockings of excited children as much appreciated gifts from Santa Claus.

Apples and oranges, sometimes studded with cloves to form pomanders, were also used to decorate that other nineteenth-century innovation, the Christmas tree. So, the celebration of tropical fruit over Christmas in nineteenth century Australia is really an evolution of this tradition, and one that given our weather and great crop we were well-placed to run with. Mangoes did not necessary oust the pudding, but were added to the feast as an extra Australian offering. As the following description of a 1903 Christmas meal indicates, Australians still often kept to tradition, but welcomed these new additions:

“I write in the afternoon, after a good dinner. A turkey, ham, and potatoes; a big plum-pudding and custard, followed by some mangoes and bananas and some muscatels and almonds. Truly, a good dinner”

“Christmas Time: along the line,” in The North Queensland Registrar, 4 January 1904, p21

While fruits such as mangoes do not appear to have ever been left in stockings by Santa as oranges or satsumas may have been, they did become a traditional gift for friends and family over the season. Giving cases of fruit, commonly mangoes, evolved as a popular practice which continues today. Relatives from far north Queensland would often send crates of fruit to their relatives in cooler climes down south. These offerings soon became predictable enough that by 1945 one less than impressed recipient complained;

One hates to offend people, but if we get another Christmas box that includes mangoes, pineapples or a watermelon I’ll scream, I know I will.

“Our First Peacetime Christmas” The Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 21st December 1945

And so it was that, like the pudding, a box of mangoes or cherries became an indispensable part of the Australian Christmas for so many. A favoured gift, a celebration of our season, a signifier of our emerging identity and a very Australian take on a Victorian tradition. Today, nothing says Christmas more to Australians than the intoxicating aroma of overripe mangoes, mixed with the essence of perspiring pine needles.

Second helpings of pudding, and an extra slice of mango

[1] Marcus Clarke, Australasian, 26 December 1868, cited in Barbara Santich, In the Land of the Magic Pudding: a gastronomic miscellany (Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press, 2000) 25-26.

[2] Meringues at twenty paces!! For a discussion of the fiercely contested ‘Pavlova Wars’ see Helen Leach, The Pavola Story: a slice of New Zealand’s culinary history (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2008), pp11-31.

[3] ‘Commercial’, in the Evening News (Sydney), 22 December, 1910, p7

Henry Lawson’s “The Ghosts of Many Christmases,” from The Romance of the Swag is online here. “That pretty girl in the army,” from Send round the hat is here.

Madeline’s book, Christmas Food and Feasting – a history, is published by Rowan & Littlefield.