Now rarely seen in its traditional form, a saddle of lamb or mutton was a prestigious cut of meat that was highly fashionable on colonial tables in the late 1800s.

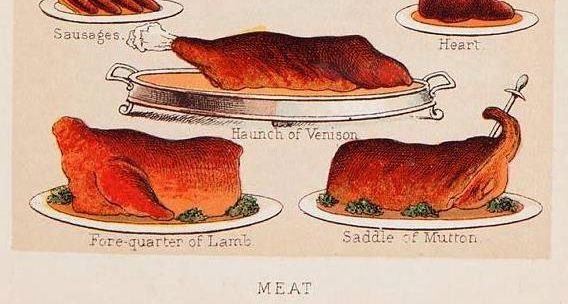

Colour plate from Mrs Beeton’s Book of household management. c1880. Caroline Simpson Collection and Research Library. © Sydney Living Museums

Tell ‘tail’ signs

As the name suggests, the saddle is cut from the back of the animal, and the saddle meat is quite familiar to us, as it is where loin and chump chops are cut from (see diagram below). Colour plates in 19th-century cookbooks, such as the one above, show what the cut looked like in the day. Its distinguishing feature is the little upturned ‘tail’ at the end of the joint. The tail is, I discovered, is the end part of the sheep’s actual tail.

Roast saddle of lamb. Photo © Jacqui Newling for Sydney Living Museums

A cut above

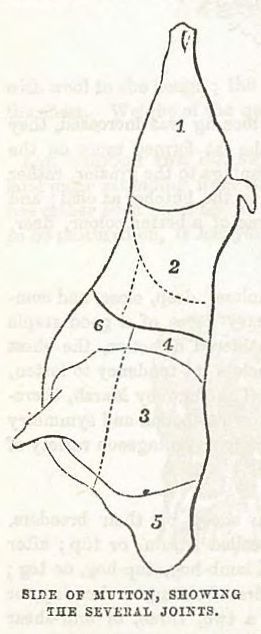

Cookbooks differ in their descriptions and diagrams, but Mrs Beeton’s 1861 Book of household management is quite specific, showing the loin section as cut number 2 in the line drawing below, extending all the way to encompass the tail. ‘The two loins,’ says Beeton, ‘when cut in one piece [from both sides of the animal] being called the saddle’.

Side of Mutton, in Beeton’s book of household management, Isabella Beeton, 1861. A facsimile, Jonathan Cape, London, 1968 p. 328 cut number 2 is the loin section and when taken as a whole from both sides, the saddle.

Saddle up!

Challenged with recreating a saddle of lamb for a television production, I approached several ‘old school’ butchers to acquire this now arcane cut. Most of them were able to provide what they call a traditional saddle, but finding one with the signature tell ‘tail’ appendage proved a little more difficult. Our friends at Feather and Bone Providores came to the rescue, cutting the meat specially for the project leaving the tail intact.

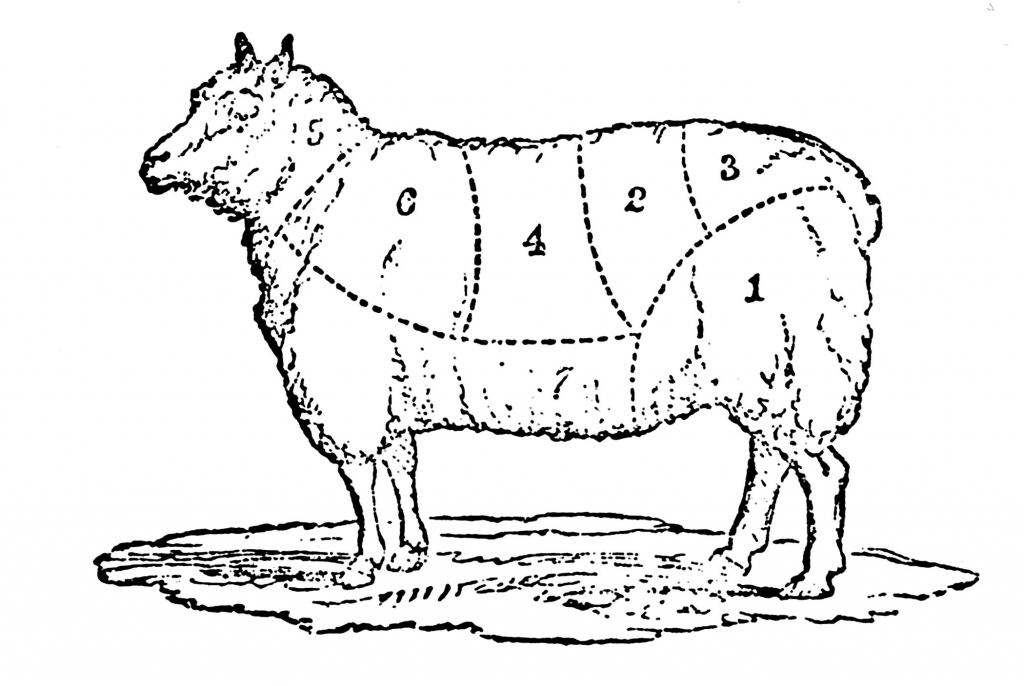

Cuts of mutton shown in Eliza Acton, Modern cookery for private families. 1855. From facsimile edition, © Southover Press, UK. 1993.

1. Leg. 2. Best End of Loin. 3. Chump End of Loin. 4. Neck, Best End. 5, Neck, Scrag End. 6. Shoulder. 7. Breast.

A Saddle is the Two Loins. A Chine, the Two Necks [ie conjoined from each side of the animal]

The tail wagging the sheep?

F&B’s Grant Hilliard explained why the saddle has been cut from our general butcher’s repertoire. In a case of the tail wagging the sheep, the butchering process is affected by the way the lamb is hung after slaughtering and the style of sectioning that is the least wasteful, and most economically efficient, to carve up the animal. Hanging fresh meat after slaughter is a necessary process to prepare the meat for butchering. In times past, sheep might be ‘butt’ hung, leaving the legs to sit at an angle to the torso, as they would have when the sheep was living. This alters the way the rump, tail and leg sit together for sectioning into accepted culinary cuts of meat. More commonly however, lamb and sheep carcasses are generally, in reference to the Greek hero’s weak point, ‘Achilles’ hung – that is, from the sheep’s equivalent of an ankle. This process shapes the meat for breaking down into our standard cuts – the hind leg particularly, extending in an elongated form from the hip joint, and extends the leg away from the tail section.

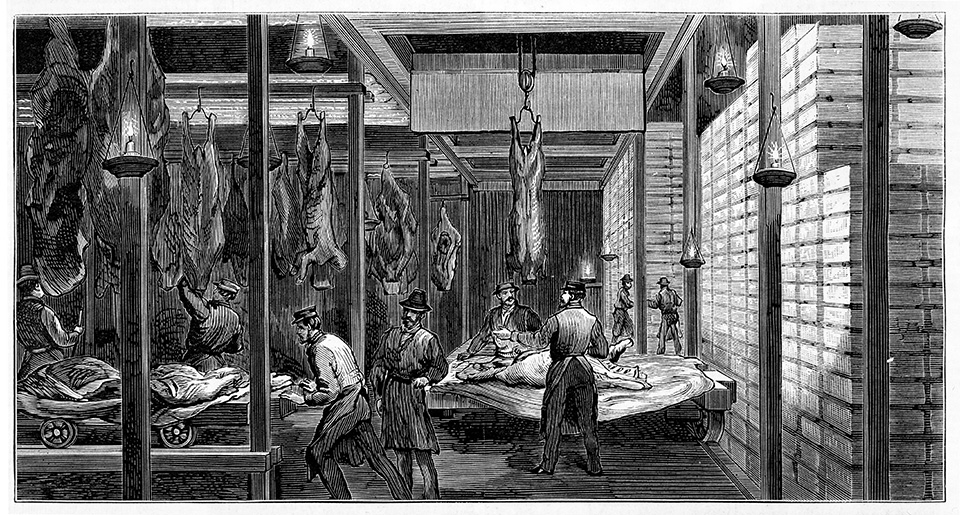

Meat carcasses hanging at MESSRS. MORT AND CO’S MEAT PRESERVING WORKS, DARLING HARBOR, SYDNEY. Illustrated Australian News 12 June 1876, p. 88 Image courtesy of the State Library of Victoria IAN12/06/76/88a.

An extravagant cut

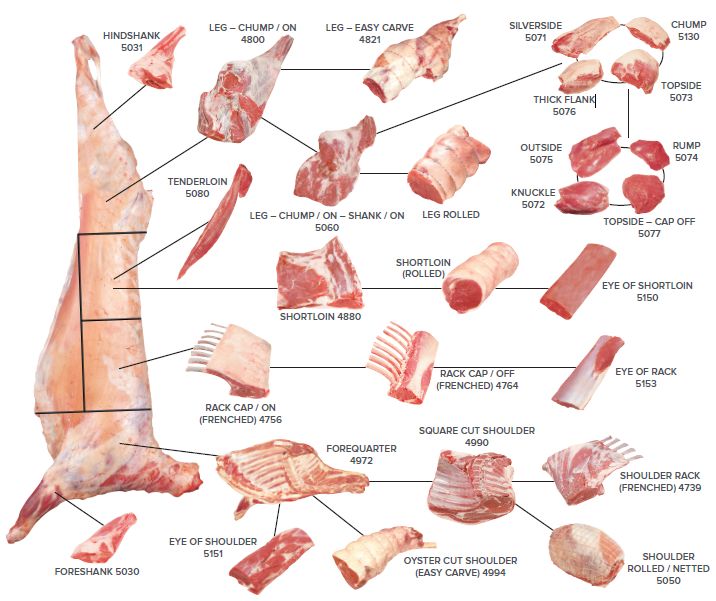

To cut the saddle with the tail intact from the Achilles-hung carcass wastes a good deal of the ‘chump’ from the rump area that is often sold with the leg, as shown on the modern MSA lamb cuts poster below (second from left at the top).

Detail from Meat Standards Australia Lamb primal cuts poster © Meat and Livestock Australia 2018 www.mla.com.au Note that the loin cut ends well before the tail section.

Even the refined Mrs Acton concurred, that the saddle ‘is an excellent joint, though not considered a very economical one.’ Albeit extravagant, the saddle was a practical choice for large dinners, as it could vary in size depending how far along the animal’s back it extended, taking in the best end of the neck. And the longer the saddle the more impressive looking the joint would be on the table. Deboned, with the lower parts of the flesh curled underneath, makes the saddle easy to carve at the table. In France it was common to stuff the centre with forcemeat – a breadcrumbs-based stuffing seasoned with herbs and sometimes offal, however English recipes suggest they preferred a ‘plain’ style of cookery, free of fancy French frippery.

Lamb carcass at Feather & Bone butchery, showing the tail section before sectioning. The saddle was cut to include the closer end of the tail, across the area marked ’20’ and down as far as the ‘230’ marking. Photo © Jacqui Newling for Sydney Living Museums

Saddle of lamb shown through the camera view. Photo © Jacqui Newling for Sydney Living Museums