This month we’re celebrating the versatile goat with a special Colonial Gastronomy program at Vaucluse House, complete with butchering and cheesemaking workshops with guest presenters Grant Hilliard from Feather and Bone and artisan goats-cheese maker Karen Borg from Willowbrae chevre cheese.

‘Nearly every cottage has its goat…’

We often think of colonial cuisine, or cookery if the idea of cuisine seems a bit highbrow, being quite limited. Our recent post on dairy produce being quite a luxury for some people supports this notion, but there were other solutions. Even if one could afford a ‘house cow’ it would be impractical to keep one in the city, or in remote areas where feed may be scarce. Many families kept a ‘milch’ goat though; they were easier to manage, house and feed in a domestic situation and offered a ready supply of milk. In his letter from the Bendigo gold diggings in 1853 Dr William Howitt assured English cookbook author Eliza Acton that with with some home grown eggs and simple pantry items even transient colonists could ‘cook a good many things’.

Stables of Lyons’ Terrace, Macquarie St south, 1842 by John Rae. State Library of NSW DG SV* / Sp Coll / Rae / 12

A valued asset or a public nuisance?

Goats were a common spectacle in colonial Sydney, roaming the streets freely, according to diarists and artworks from the time. Godfrey Mundy paints a colourful image of the chaos and antics that goats could cause around town:

With varied success have I, Quixotte-like, sallied forth to the rescue of some poor goat, whose piteous bleat called eloquently for help… That picturesque animal, the goat, by-the-by, forms a conspicuous item of the Sydney street menagerie—amounting to a pest little less dire than the plague of dogs. Nearly every cottage has its goat or family of goats. They ramble about the highways and by-ways, picking up a hap-hazard livelihood during the day; and going home willingly or compulsorily in the evening to be milked.

Woe betide the suburban garden whose gate is left for a moment unclosed. Every blade of vegetation within and without their reach has been previously noted by these half-starved vagrants. In an instant the bearded tribes rush in—where angels (terrestrial) almost feared to tread; and in a few seconds, roses, sweet peas, stocks, carnations, &c. &c. are as closely nibbled down as though a flight of locusts had bivouacked for a week on the spot; and the neat flower-beds are dotted over with little cloven feet, as if ten thousand infantine devils had been dancing there—a juvenile sabbat. Godfrey Mundy. Our Antipodes p48-49 1852.

One First Fleet convict was delighted to happen upon a goat which had died in ‘innocent’ circumstances. But being of the ‘criminal class’ their gourmet ideas of making it into a pie drew unwanted attention from the authorities.

To Day two Men were taken up on Suspicion of having killed [a] Goat, and made a Pie of some part of it… and one of the Men was to be married the next Day, they took the Liberty of cutting some of the Meat off, to make a Pie for the Wedding dinner. George Worgan, 1788

Meet our resident goats, Pan and Casper

We’d be very remiss to allow our very own goats at Vaucluse House free reign (imagine the feast they’d have in the gardens), though there have been the odd times when Pan or Casper have taken advantage of an unlocked gate, creating great entertainment for our visitors and some unexpected animal wrangling tactics from the staff, yours truly included. If you haven’t visited Vaucluse House for a while, you can meet the animals here. Interestingly, William Wentworth wouldn’t allow Sarah to keep goats on the estate, but they were very much a part of the Sydney landscape, and often feature in colonial artists’ depictions of Sydney street, town and landscapes.

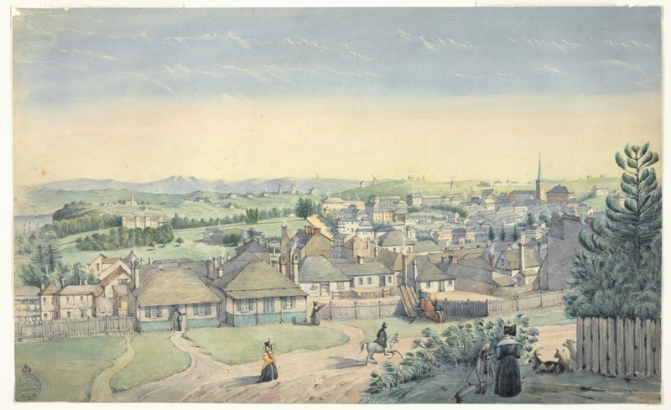

Millers Point Sydney from the Flagstaff Hill by John Skinner Prout, c1842. Beat Knoblauch Collection

[View from Flagstaff Hill, ca. 1844 / attributed to Joseph Fowles]. State Library of NSW V1 / 1845+ / 2

Broughton St / Darlinghurst / by Garling c 1846 [i.e. possibly Brougham Street, Woolloomooloo / [attributed to Frederick Garling]. State Library of NSW SV / 121.

Carol Liston. Sarah Wentworth – mistress of Vaucluse. Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. 1988.

William Howitt. First catch your kangaroo; a letter about food written from the Bendigo goldfields in 1853. The Libraries Board of South Australia.

Worgan, George B. Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon. 1788.

![95 and 97 Cumberland St The Rocks H Stuart Wilson 1902 95 and 97 Cumberland St [The Rocks] H Stuart Wilson, 1902](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2014/06/618x386xML1436-GOATS-ROCKS-1024x640.jpg.pagespeed.ic.OUXDugjMEf.jpg)

![South Head The Gap c1855 South Head [The Gap], c.1855](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2014/06/xa128553r-ML623-south-head.jpg.pagespeed.ic.B3-LKX4981.jpg)