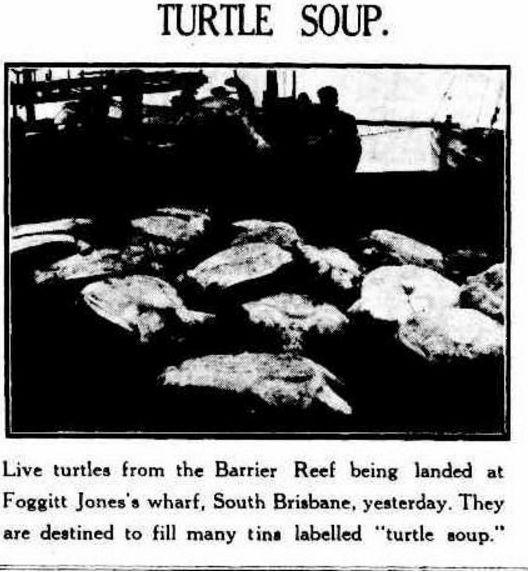

When the Prince of Wales visited Sydney in 1920 (not Charles, but Queen Elizabeth’s uncle, who would later abdicate for Wallis Simpson), a grand ball was held at Government House. The menu included consomme tortu or turtle soup. There was still a demand for genuine turtle soup well into the 20th century, harvested from Queensland waters, according to newspaper reports [1].

‘Turtle soup’ The Brisbane Courier, November 14, 1931, p. 16. Accessed via TROVE, National Library of Australia

‘an item of luxury’

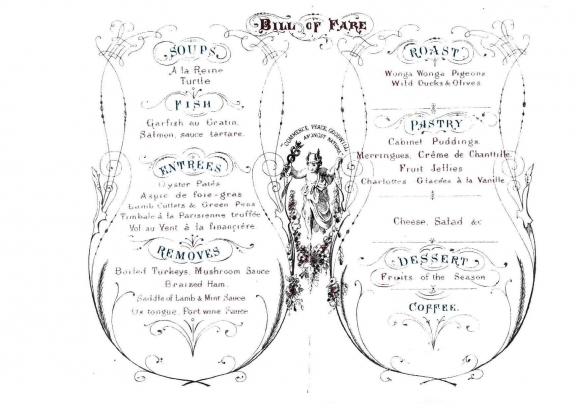

For the aspiring-to-upper middle classes of nineteenth century England, turtle was a symbol of status and sophistication. Fresh turtles, imported from the West Indies, were sold whole, to be kept alive until needed for the pot, with the shell being reserved as a prized serving dish or as a collector’s trophy. Mrs Beeton dedicates almost three pages of her Book of Household Management to turtle, ‘an item of luxury’, with elaborate instructions on how the creature should be dismembered and the different ways to cook each part of its meat. It is unlikely that many domestic households would have the opportunity to deal with a real green turtle – only a capable and accomplished cook would be entrusted with such an expensive delicacy. By the mid-century turtle soup concentrate was sold in ‘hermetically sealed canisters’ (tins) at about £2 per two-quart (2.4 litres) can, still a hefty sum. Turtle soup -particularly ‘a la Reine’, a white cream-based soup – appears on Australian banquet menus such as the one below from The Sydney Exchange in 1874. ‘Potage tortue’ was the soup of choice at the Sydney centenary banquet in 1888. Fresh, from Queensland waters we presume, for such a prestigious occasion; the Exchange may have used tinned …

Merchant Shipowner’s Banker’s and Trader’s annual dinner menu, The Sydney Exchange, 1874. State Library of NSW Ephemera/Menus

Mock Turtle

Never to miss out on something relishingly good, a solution was found for poorer classes in the creation of “Mock Turtle” soup. It was popular in the 1700s and maintained its place on tables well into the 20th century, reaching its demise in Australia after WWII. Basically, it is a rich beef broth made from a calf’s head, a part of the animal now not commonly used, except for the cheeks that have become trendy of late. Enriched with Madeira or sherry, aromatic herbs, vegetables and diced ham, the resulting broth was particularly silky and smooth and would be served as a consomme or, for a more ‘economical’ version, with its meaty bits returned to it as a more hearty soup.

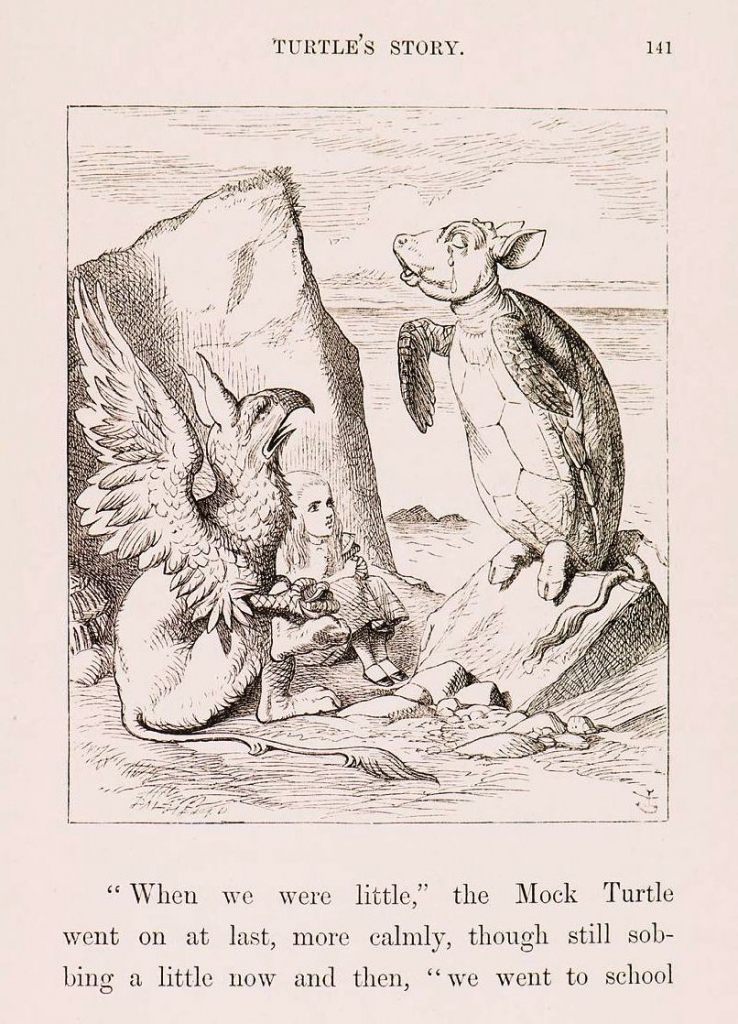

The Gryphon and the Mock Turtle illustration by John Tenniel in Lewis Carroll, Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, Macmillan, London, 1872. State Library of NSW DM/827.8/D645.1/4A1

The Alice in Wonderland Mock-Turtle character, which sports a calf’s head, tail and feet – key ingredients in Mock Turtle soup, indicate the dish’s ubiquity in the 19th century.

Beautiful Soup, so rich and green,

Waiting in a hot tureen!

Who for such dainties would not stoop?

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Beau—ootiful Soo—oop!

Beau—ootiful Soo—oop!

Soo—oop of the e—e—evening,

Beautiful, beautiful Soup!“Beautiful Soup! Who cares for fish,

Game, or any other dish?

Who would not give all else for two

pennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Pennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Beau—ootiful Soo—oop!

Beau—ootiful Soo—oop!

Soo—oop of the e—e—evening,

Beautiful, beauti—FUL SOUP!

A different aesthetic

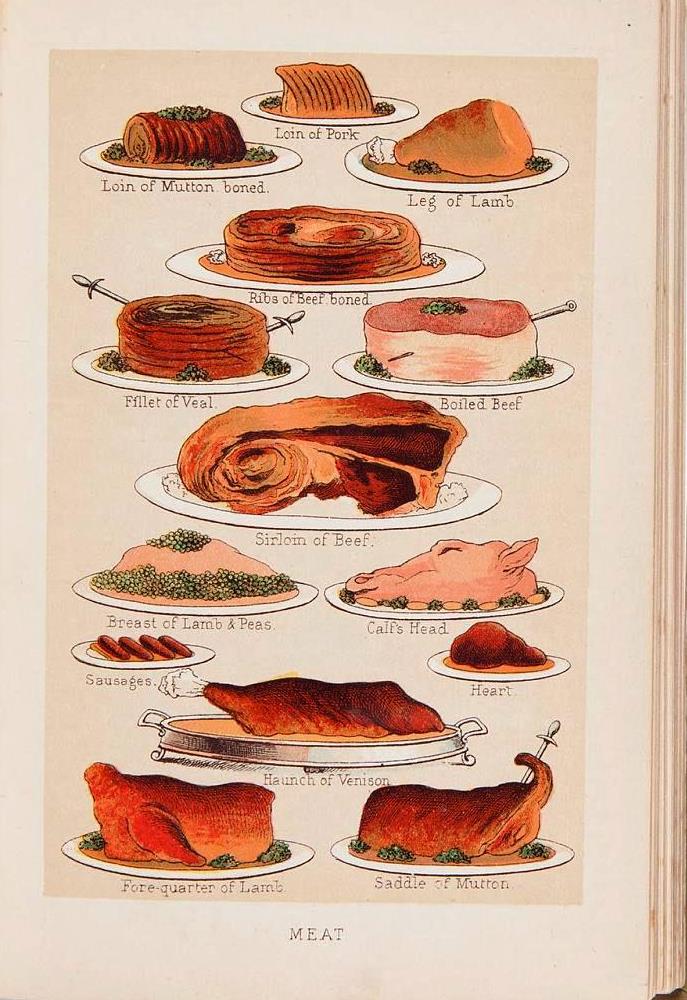

Calves’ heads themselves were popular main course dishes on a 19th-century table, served whole or halved, boiled and then sometimes coated in seasoned crumbs and baked. Cookbooks featured colour plate images of how to adorn them for the table (see image below) with explicit instructions on to how to carve them and get at the best bits (cheeks, jowls and palates). The eyes were, for some, a delicacy.

Serving suggestions for meat. Mrs Beeton’s Every-Day Cookery and Housekeeping Book, Isabella Mary Beeton, London, c1895. Caroline Simpson Library and Research collection. © Sydney Living Museums. Note the calf’s head below and right of the sirloin at centre.

Heads up

It is hard to imagine that any diners would tolerate such a large and identifiable part of an animal on the table, but such was the acceptance of animal food in past times – it is only relatively recently that we have rejected whole cuts and offal, and prefer to disassociate our food with its true origins and form; rather than garnish we disguise. When we decided to do a Colonial Gastronomy program on Meat at Vaucluse House I felt compelled to attempt this dish, all in the name of authenticity and the knowledge gained from practical experience.

A gastronomic challenge

Apart from a strong resolve, the hardest part was acquiring a calf’s head, and then a pot large enough to cook it in. Fortunately my local butcher saved me a trip to a meat-works, although even then the reality was somewhat confronting (see image below but not if you’re squeamish) and a caterer friend provided me with a 30 litre pot. The pot was so big I had to use the barbeque, which was also a good idea as I wasn’t sure I wanted the house to smell of boiled meat. As I was unable to buy a head with the skin on, I wrapped the head in muslin so that I could retrieve it from the pot once it had cooked without damaging it.

I will spare you the rather grotesque end results, but you can watch Heston Blumenthal or the Supersizer’s Go Victorian (boiled calf’s head) ‘revive’ calf’s head in their TV shows, but beware, you see the raw materials in all their glory. (Actually Heston’s looked peculiarly benign, as the stylists ensured its eye was closed).

Local butcher John Elvy with calf’s head. Photo © Jacqui Newling

Sources:

For example The Canberra Times, May 21, 1958; The Brisbane Courier, November 14, 1931

Banquet menu from The Sydney Exchange 1874 – Ephemera Collection. State Library New South Wales

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s adventures in Wonderland, Macmillan, London, 1872

The Mock Turtle’s Story, in Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, http://www.authorama.com/alice-in-wonderland-9.html