If you’ve sat near a roaring fireplace you’ll know that you can get a tad cooked. While pole screens were an option in the drawing room, when dining there was another quick fix: introducing the chair screen.

Pole screens were a typical Regency and Victorian furnishing, imaginatively named for the tall pole on which a screening panel could slide up and down. You positioned the screen so that your body could be warmed, but your face shielded from the direct heat: no-one wants an unfashionable rosy tan! These were highly decorative domestic furnishings, and often a focus for home crafts from painting, beading and embroidery to featherwork and collage. This is what Austen’s ‘Mr Bingley’ is referring to when he says of young ladies that “They all paint tables, cover screens, and net purses. I scarcely know anyone who cannot do all this, and I am sure I never heard a young lady spoken of for the first time, without being informed that she was very accomplished.” [1]

At several of our properties you’ll see pole screens brought out when the houses are ‘wintered’ each year. This example, made from Tasmanian blackwood, is from the Caroline Simpson collection and can be seen seasonally at Elizabeth Bay House. While the front features an embroidered arrangement of roses and lilies in an urn, the back has card panels painted with sparrows amongst morning glory tendrils and flowers. The familiar version by British Regency designers such as Hepplewhite often have a panel that resembles an armorial shield. More robust, two legged versions dominate in later years, and some could incorporate writing or work desks (is there ANYthing those creative Victorians couldn’t – or wouldn’t – design?)

Pole screen showing the beaded front panel. Caroline Simpson Collection, Sydney Living Museums EB2007/3

Banner screens, as the name suggests, incorporate a cloth ‘banner’ rather than a solid panel, and resemble a small gonfalon or vertical pennant. An example seen in the Vaucluse House breakfast room is completely beaded and fringed.

Meanwhile, back at the table

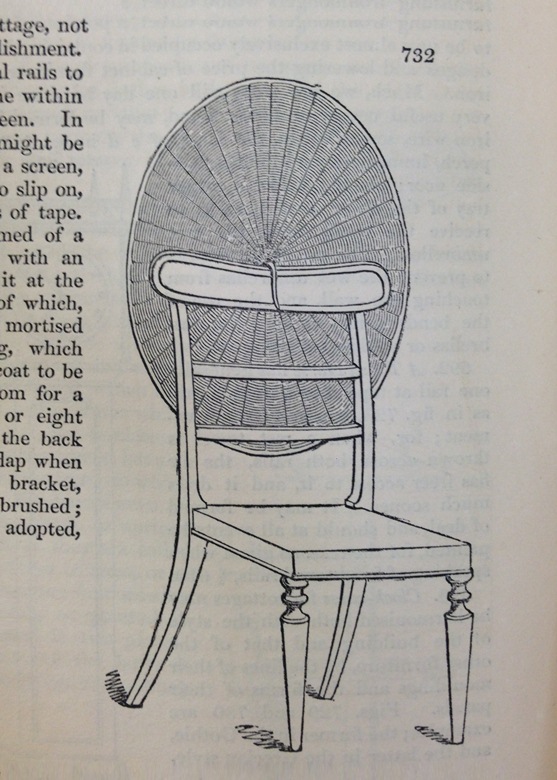

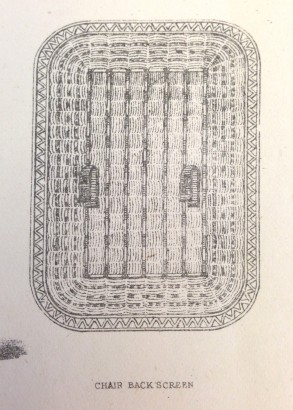

Large free-standing screens in a dining room are trickier, as they obstruct movement around the table and you would potentially need a row of them to properly shield all the diners who were sitting close to the fireplace. The alternative was the chair, or ‘back’ screen. These could be round, square or rectangular, were typically woven from thin split cane or wicker, and seem to have become common after the mid 19th century. Eponymous design writer John Claudius Loudon published this design for a round chair screen in 1833:

Design for a chair screen; Fig. 732 in J.C. Loudon, An encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture and furniture, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, London, 1833. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums RB 728.370941 LOU

6955 Screens may be wanted in a cottage as well as in the palace. A lady has sent us a cottage fire screen, made of straw, with a hook attached to it by which it is hung on the back of a chair, figure 732, which will answer very well when sitting with the back to the fire. To shield the face a standard fire screen is required but we should leave the reader to contrive one for himself from the designs, which you will find in another part of this work, under the Head[ing] of fire screens for villas. [2]

A fragile survivor

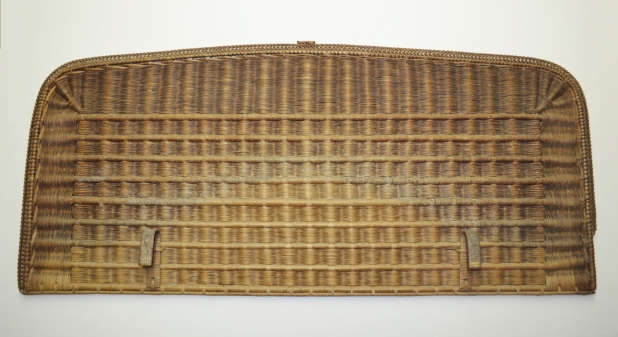

The collection at Rouse Hill contains two tightly woven cane chair-screens, designed to hook over the horizontal top or central rail on the back of a dining chair. Dating to the occupancy of Edwin Stephen and Bessie Rouse, they rose high enough to at least shield the neck of the sitter, but more likely their hair as well – which would stop a pomade running or wax hair ornaments melting; at Rouse Hill the dining room fireplace is only 2 feet behind the chair backs on that side of the table. The two screens match a number of rectangular and oval heat mats for the dining and serving tables, and splash backs for wash stands. Only one of the hooks that attached this screen to the chair survives:

In a better condition, this matching splash-back from a bedroom wash-stand retains both its curved hooks:

Woven cane splash back, showing the hooks that clip onto the back of the wash stand. Sydney Living Museums R87/71:6

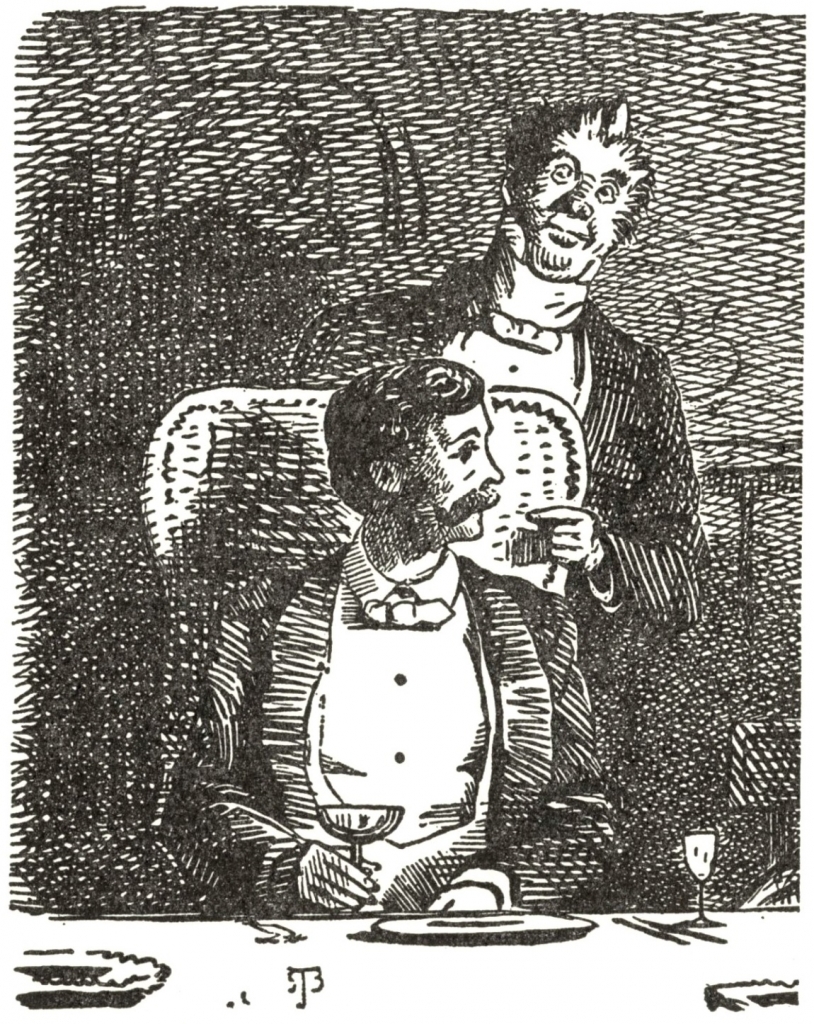

Reproduced from Gloag’s ‘Short Dictionary of Furniture‘ (2nd edn. 1972) is this scene of a diner and butler. Originally published in ‘Judy; or the London Serio-Comic Journal‘, London, March 25, 1868 it shows a near identical woven cane screen, with the same rounded corners, in use. The curve of the fireplace opening can just be seen to the left of the diner:

Dining scene from ‘Judy’, March 25th 1868, showing a chair back in use. Reproduced from John Gloag, Short Dictionary of Furniture, Allen and Unwin, London, 1972

A catalogue ca.1870 by Smee and Sons, a London based furnishings manufacturer, illustrates a similar “wicker chair-back screen”, which retailed at between 6 and 8 shillings:

Chair back screen from the W. A. & S. Smee and Sons catalogue, London, ca.1870. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TCQ 749.2048 SME

DIY fire screens

Feeling crafty? Given that Smee & Sons are no longer with us, this DIY guide to making a chair screen is from the 1850 ‘Lady’s Housebook’ (as quoted by fellow historic food blogger Pat Reber on her site):

“CHAIR-SCREENS.—To make a very good chair-screen, get a large sheet of the thick stiff pasteboard used by bookbinders and trunk-makers, (of whom it can be obtained,) and with a knife pare off the edges and trim it to the required size. It should ascend sufficiently above the back of the chair to screen the neck and shoulders of the sitter. Make a double case (like a pillow-case) of dark chintz or moreen, open at one end, to slip over the pasteboard. At each of the lower corners, sew a strong string of stout ribbon or worsted tape, and place two other strings about half a yard farther up, on the side edges or seams of the cover. When the cover is finished, slip it over the pasteboard, and sew it along the bottom edge, to keep the board from falling out. When ready for use tie it by the strings to the outside of the back of the chair. Three or four of these screens will be found very convenient in dining-rooms, to screen from the heat the backs of those persons who sit on the side of the table next the fire. Also, they will save the chairs from being scorched and blistered.

You may have slighter chair-screens, by simply making cases of thick moreen, without pasteboard; leaving the lower end open to slip down over the chair-back.” [4]