2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the Commonsense Cookery Book – a book that has a special place in many a cook’s heart – including mine. No matter how many trendy, glossy, gourmet, exotic, quirky, best-seller or big-named chef’s cookbooks you find on a good cook’s bookcase, there’s usually a comparatively diminutive Commonsense Cookery Book there too. And testament to its success over the past 100 years, its often this practical little kitchen classic that is the most well-thumbed of a family’s cookbook collection.

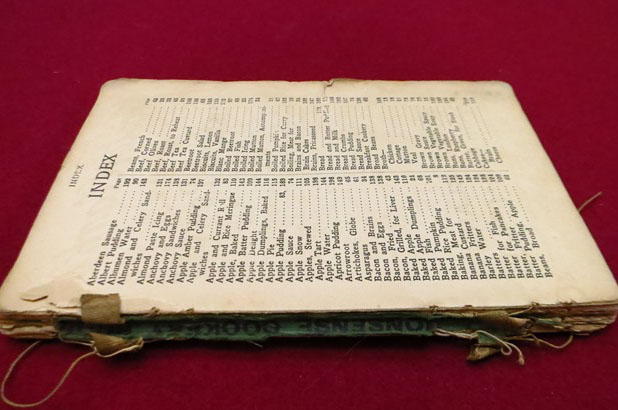

The Rouse family cookbook collection includes an early edition Commonsense Cookery Book (shown above), but its battered state makes it difficult to identify exactly which year it was published. The last remnants of its green cloth cover indicates that it is a pre-1920 edition. It has been fascinating to compare this early Rouse family edition with my faithful little 1980s version, and now, with the 2014 centenary edition.

Home Econ Institute of Aust (NSW Div), The commonsense cookery book: the kitchen classic, HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd, 2013

The Commonsense Cookery Book has always been an instructional text and its practical, no-nonsense, reliable, useful approach to cooking is what has sustained it throughout the hundred years. It was originally published to support cookery teaching in New South Wales’ schools, but today it enjoys a far more universal audience, and has sold over a million copies in its time. I’m told that it is routinely given to sons and daughters as they move out of home, or given as a wedding gift with a cheque slipped inside.

Where are the lamingtons, you ask?

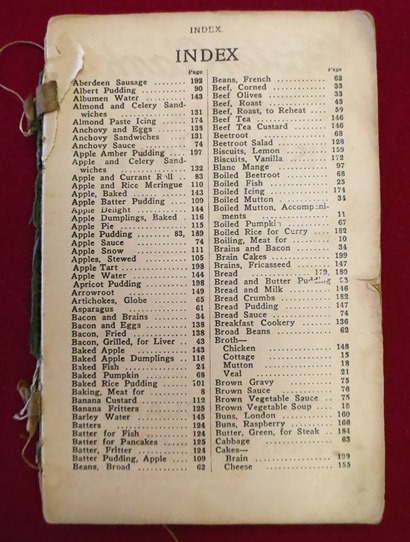

For the culinary historian, the various editions offer a wonderful resource, enabling us to trace the evolution of our culinary heritage – or at least the dishes which were determined necessary by the teaching authorities – over the past hundred years. The early editions were written before vegemite, lamingtons, pavlova, peach Melba, and Anzac biscuits and pre-date the multi-cultural influences, experiences and culinary expectations that global travel and international migration has afforded us.

Some of the old faithfuls that have stood the test of time have been modified to suit (or in some cases, I suggest, help shape) modern tastes, in response to changes in nutritional awareness – suet, clarified fat and dripping have been replaced with butter, margarine and olive oil. Mercifully, but telling for our mothers’ and grandmothers’ culinary past, a good stove, frying baskets and asbestos mats are no longer kitchen requisites; electric beaters, microwave safe dishes and a chinois however now are.

The lamingtons, pavlova, peach Melba, and Anzac biscuits these have all taken their rightful place in subsequent editions and toad in the hole, ox-tail stew and Aberdeen sausage have given way to stir fries and satay skewers, spaghetti bolognese and moussaka, goulash and ratatouille. Offal has all but disappeared; steak and kidney pudding survives but brains, tripe and ox-tongue have fallen from grace. Rabbit dishes remain but kangaroo is obstinately illusive. The Curator and I were quite surprised to think that the old colonial standby, kedgeree, had slipped off the menu but discovered it included in the Fish chapter. We were happily surprised to find that old fashioned sago puddings, blanc mange and seed cake still have a presence, and good old Irish stew (with a nod to St Patrick’s day earlier this week).

Everyone seems to have a fond memory and deep respect for the CSCB – I still return to my 1980s copy every so often to double-check ratios for simple classics such as scones and pikelets, apple crumble topping , boiled custard and Yorkshire pudding batter. Whats your favourite recipe from yours copy?