A native garden among the skyscrapers

Yana Nura, “to walk on Country” is a native garden at the Museum of Sydney that invites visitors to reflect, reconnect and learn about Aboriginal culture, past and present, on Gadi Country. Located on the outdoor mezzanine that overlooks the site of Australia’s First Government House and the area that the first colonial garden was installed on Aboriginal landscape, in 1788.

The garden responds to ‘the cultivated landscape that Aboriginal people created and maintained for millennia, [which is] now surrounded by skyscrapers’ and reminds us that ‘although the landscape has changed, it continues to provide for those who care for it.’ The garden features some of the plants that are native to the area, providing local Sydney Aboriginal people with culture, food, medicine and tools for everyday life’ historically and currently.

Deeper meaning

But ‘the governor’s garden’ area holds far more significance than the place where introduced plant species were trialled for colonial benefit. It was the final place of rest for at least two Aboriginal people who were at the forefront of the impacts of dispossession in the 18th century – Arabanoo and Barangaroo, whose stories are told alongside the stories of the plants. Arabanoo was kidnapped and held captive at Government House for almost six months before dying from the smallpox epidemic that swept through the Aboriginal community in 1789, and Barangaroo, who often paid visits to the governor with her husband Bennelong in the early 1790s. Their presence in this place reminds us of Aboriginal people’s struggle and their resilience in the ongoing colonial process.

The plants include:

Durawi – Lomandra Lomandra longifolia has long strong grass-like leaves that can be used for weaving, and have long been used to make nets and baskets.

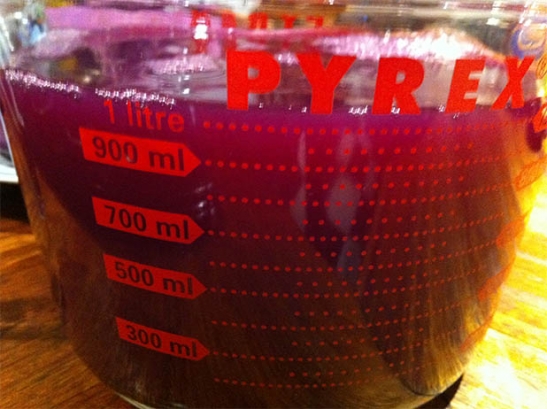

Tacoba – Lilly pilly Syzygium australe The tart-tasting, pink-to-purple-coloured berries are eaten or made into a drink by local Sydney Aboriginal people. They also make a wonderful ruby-coloured jelly preserve (see recipe below).

Gurrendurren – lemon-scented tea tree Leptospermum petersonii, the leaves of which are used medicinally

Polkulbi – Blue flax lily Dianella caerulea. Local Aboriginal people eat the deep blue berries, sweet-tasting berries whole, including the small crunchy seeds (beware when harvesting – some other species of Dianella can be toxic!)

Numura – Grevillea Grevillea ‘Robyn Gordon’, from which local Aboriginal people make a sweet-tasting drink from the flowers.

Warrigal Durawi – Warrigal greens Tetragonia tetragonioides grows prolifically and tastes similar to spinach. The leaves contain oxalates, which can make people ill if consumed in their raw state.

Bawa (meaning shrub or bush) – Native mint Mentha australis has a delicate minty flavour and is used by local Sydney Aboriginal people to treat colds and headaches.

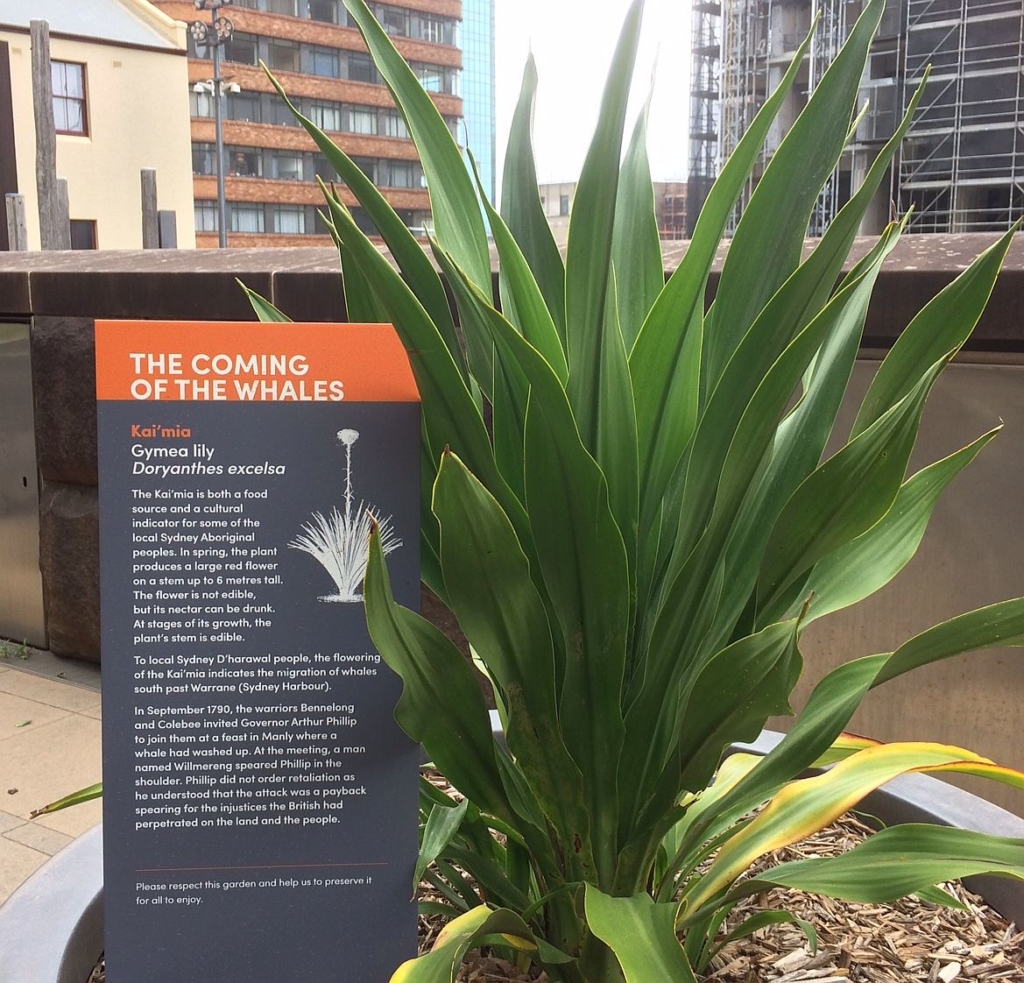

Kai’mia – Gymea lily Doryanthes excelsa, its flower produces nectar which can be used as a drink.

Talara’tingi – Flannel flower Actinotus helianthi which can be made into a tea to soothe grief, and plays an important role in sorry business.

Gadi – Grass tree Xanthorrhoea arborea the base of the leaf can be eaten raw or cooked, and the plant produces a resin that can be used as an adhesive. Parts of the tree are highly valued in women’s practices, as an aid during childbirth.

Sharing knowledge

Created in collaboration with D’harawal Knowledge Holder’s Circle and Saltwater Knowledge Keeper Shannon Foster, the Yana Nura garden space is one of several new installations, programs and knowledge sharing initiatives at Museum of Sydney, including Cadigal Place, the Yura Nura gallery and education program, Garuwanga Gurad which means “Stories that belong to Country.”

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

SLM project curator Aiesha Saunders, Saltwater Knowledge Keeper Shannon Foster and D’harawal Knowledge Holder’s Circle.

Lilly Pilly jelly

Ingredients

- 8 cups lilly pilly berries

- 1kg green apples

- sugar

- 1/2 cup lemon juice

Note

Lilly pilly trees grow prolifically around Sydney – look out for them in parks, sports fields and hedging along front fences. You can use the same recipe for Rosella Jelly, using the exotic looking calyxes in place of the lilly pilly fruit.

The good thing about a jelly is that except for cleaning the fruit thoroughly, to remove any dirt, pollution or bugs, there is little preparation needed to extract the jelly base. The green apples add pectin, helping to make the mixture set, and adds to the volume produced. If you want to use the native fruit only, ensure they are under-ripe, and quite acidic, a good indicator of pectin content.

Like many jams and jellies, this recipe involves a two-day process.

Directions

Wash the lilly pilly berries in cold water, removing any leaves, grit or spiders' webs. Drain the berries and put them into a large saucepan or stockpot (8-litre capacity minimum). If using store-bought apples, scald them in very hot water to remove any excess wax. Cut the apples into 1cm chunks and add them – seeds, core and all – into the pan. Add enough water to just cover the fruit and bring to the boil. Reduce to a simmer, cover the pan and continue cooking for 30–40 minutes, until fruit is very soft. Allow to cool a little. | |

Strain the juices from the cooked fruit into a bowl using a sieve lined with three layers of muslin (or use a new chux cloth). Reserve the juice. Bundle the drained fruit in more muslin (a bit like a plum pudding) and secure with string. Tie the bundle of fruit to the handle of a wooden spoon and hang it over a deep bowl or pan. Allow any remaining juices to drip into the pan overnight, but don't be tempted to squeeze or apply pressure – this can result in a cloudy jelly. | |

Next day, discard the bundle of solids. Add the first quantity of strained juice to the batch extracted overnight and transfer it into a clean saucepan or stockpot. Warm gently over medium heat and once the liquid has reached simmering point, add sugar at an equal measure to the quantity of juice. Stir gently until the sugar has dissolved then add the strained lemon juice. Don't worry if the mixture appears cloudy at this point, the sugar will help to clarify it as it cooks. | |

Boil the mixture rapidly, stirring as it thickens to prevent burning and to minimise the risk of the jelly bubbling over, until setting point has been reached, which can take up to an hour. If the jelly will not set, jamsetta or a similar pectin product can be used, following packet instructions. | |

Ladle into sterilised jars and seal immediately. | |

Cook's tip: The boiling process may produce a foamy scum; this is okay while cooking but make sure you skim off the scum using a large stainless steel spoon before bottling. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe