Last week the air at Elizabeth Farm was rich with the aroma of Indian curries cooked on the wood stove.

Part of the experience of visiting Elizabeth Farm is the evocative smell of spices and cooking. On weekends when visitors walk in to the kitchen the aroma from a frypan of onions sizzling in a Madras curry mix hangs in the air. Smell is one of the most effective prompts for memory – it was the smell of madeleines, sponge cakes, that provided the starting point for Proust’s monumental work ‘In search of Lost Time’.

At Elizabeth Farm smell is one of a series of sensory prompts created to start a train of thought: in this case, ‘were there really curries cooking here? That early?’ This then leads to a discussion not just about recipes but about trade, trade routes and contact. Often visitors talk about what they smell in their own kitchens, or memories from their childhood.

(For information on the colonial taste for curries pop back to ‘Curry culture‘, and for recipes just type ‘curry’ in the search box to the left.)

At the wood stove

While we have the proverbial ’embarrassment of riches’ of Indian restaurants and cafes at nearby Harris Park, we’ve long talked about cooking on the wood stove and testing what it can do. Last week colleagues Devanghi and Paul took up the challenge. Delicious empirical research!

Devanghi working her magic at the stove. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

What particularly interested me was how someone who had never used a wood stove like this before would find the experience. The result? Devanghi, cooking a northern Indian chicken karahi curry [1], found the process took about half an hour longer than using a modern stove. The major challenge was maintaining a high heat; keeping the curry at a low boil/high simmer meant constantly stocking the fire, and having the damper – the sliding plate that controls airflow in the chimney and hence the rate of burn – behind the firebox about half way out the entire time. All up about 20 pieces of wood went in; you quickly sympathise with a cook who stood in front of a fire like this for hours on end through a hot summer!

Paul’s Rogan Josh curry simmering on the range. photo (c) Paul Smith for Sydney Living Museums

The stove was actually very responsive; Paul (cooking a lamb Rogan Josh) described being able to quickly vary the heat from a low to a high simmer just by moving the pan of his curry around on the range top. Even a few inches side to side was all it took to finely control a simmer.

Checking on the curries. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

In everyday use

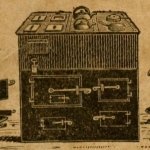

As we devoured the curries we discussed how this stove was originally used. Many visitors ask how it was possible for a whole series of dishes to be cooked on what seems a small stove (though its almost twice the size of my stove at home!). We had a large pot and a deep frypan side by side; that easily left plenty of space for another 6 pots, even a bain marie with a selection of saucepans. You could have 4 pots boiling, and the rest on heats ranging from a high to a low simmer. Add to that the small, 2-shelf oven, and suspend a roast in front, and you have a considerable amount of cooking space.

Given the number of people the dining room at Elizabeth Farm can accommodate at a formal meal (it fits almost three times into the huge dining room at Elizabeth Bay House, and the table is most comfortable when extended to take no more than 8 or 10), I would expect no more than 4 to 6 dishes in any course, in addition to the removes – the soup, fish, and a roast for example. As a ‘dish’ could range from a ragout or a curry with many ingredients, to a dish of rice, or a simple boiled vegetable served with butter, you can see that this range and a competent cook could easily cope with a 3 course dinner.

Delicious curries cooked on the stove at Elizabeth Farm. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

We did take one shortcut though: boiling a pot of water for the rice was threatening to take a very long time so we used the modern kitchen. That in itself is a valuable lesson in kitchen use, one that we’re going to examine in greater detail in the future when we discuss the ‘set kettle’. Stay tuned!

Second helpings

[1] Made with onions, tomatoes, cashews and capsicum, and finished with cream, a karahi curry is one of the subcontinent’s best known curries, and with minor variations, is found right across Northern India and Pakistan. You can easily find recipes online. Devanghi has a tip for adding the cream – first, add some of the gravy (as it would be termed in the 19th century) to the cream in a bowl and mix well. Pre-mixing it like this will stop the cream splitting when you add it to the dish. We had ours served with rice and warm naan. There were no leftovers.

Karahi is also known as ‘kadai’ chicken; a ‘kadai’ being the wok-like cooking pot used to cook the dish.