Welcome this week to guest contributor, Heather Hunwick, who takes us into the story of Sydney’s early markets, and from a nostalgic allusion to London’s bustling Leadenhall Market, to the splendid Queen Victoria Building 110 years later.

Our regular readers will be familiar with the elaborate dinner menu enjoyed by the officers of the First Fleet officers on June 4, 1788 in celebration of the birthday of King George III, described by 1st Fleet surgeon, George Worgan and re-enacted with many a huzzah for the Eat Your History:

A Shared Table exhibition :

…about 2 O’Clock we sat down to a very good Entertainment, considering how far we are from Leaden-Hall Market it consisted of Mutton, Pork, Ducks, Fowls, Fish, Kanguroo, Sallads, Pies & preserved fruits. The Potables consisted of Port, Lisbon, Madeira, Tenerife and good old English Porter. [1]

This week we have a guest contributor, Heather Hunwick, author of The Food and Drink of Sydney: A History [2] who picks up on Worgan’s nostalgic recall of London’s ancient, bustling Leadenhall Market, and its significance in Sydney’s colonial history.

Sydney markets, the first hundred years

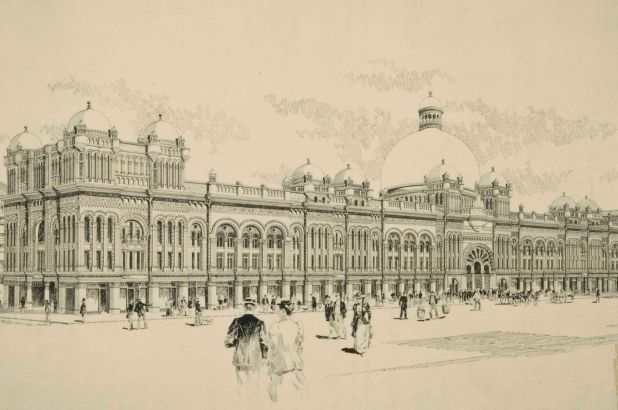

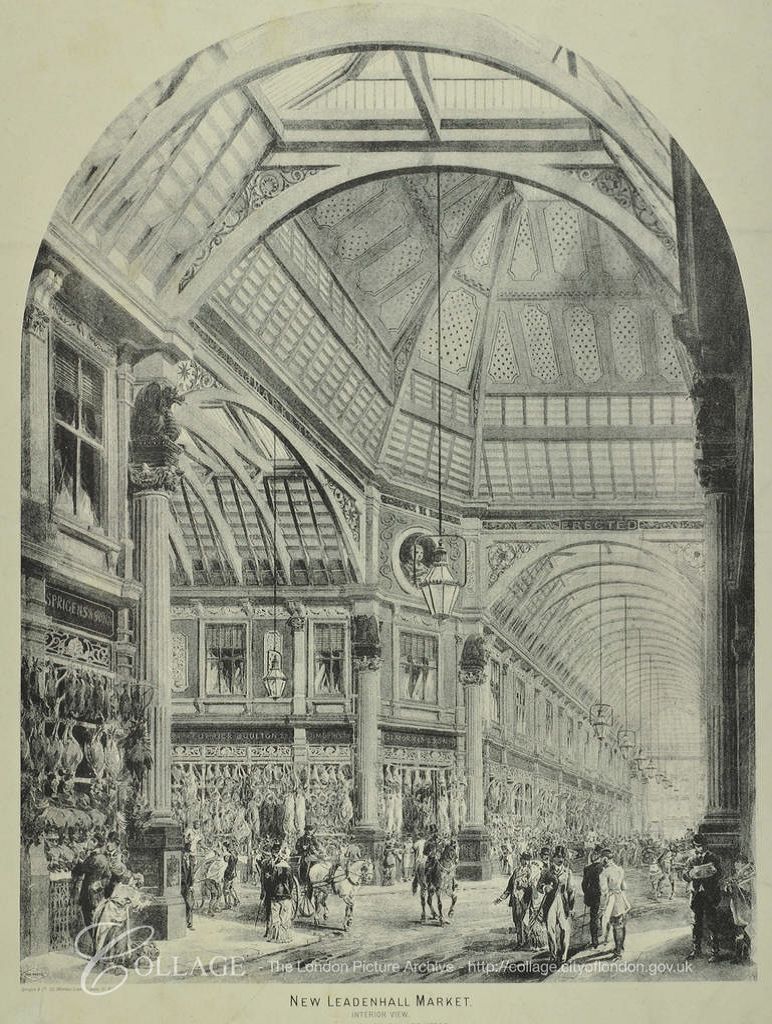

Leadenhall Market Interior, 1883. © London Metropolitan Archives, Collage Record no: 319683: Catalogue No.: SC_PZ_CT_02_0095

The Leadenhall Market, which dates from the early 1300s, was originally a meat, game and poultry market in what was once once the centre of Londinium – Roman London. As Worgan’s reference to it indicates, it remained a dominant feature of Georgian London’s townscape. Leadenhall Market as it is seen today bears striking similarities with Sydney’s ‘grand dame’, the Queen Victoria Building (QVB), which was the result of a ‘moveable feast’ of market places in colonial Sydney.

Supply and demand

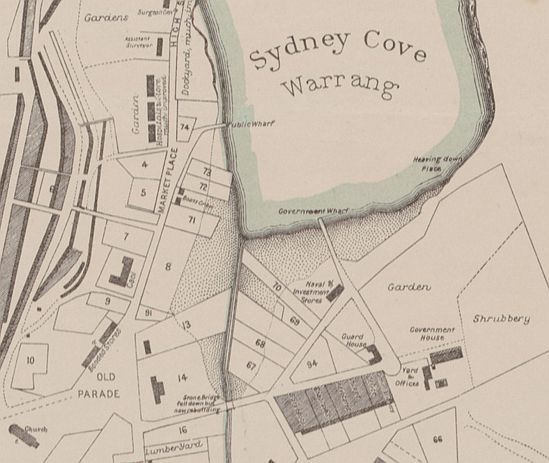

In 1792, just four years after the arrival of the First Fleet, there was surplus produce in the colony – locally raised foods and imported commodities. A range of food products are listed for sale in Sydney and Parramatta, including livestock and poultry, fresh and cured meats, locally grown grain and vegetables, and imported goods such as tea and sugar. [3] A dedicated market place had been established at Parramatta but it appears that in Sydney the market was a less formal affair, with sellers bartering their wares near the government wharf on the western side of Sydney Cove [4]. In 1806 it was complained that:

“great inconvenience attends Boats which come loaded with Vegetables and other Articles for barter with the Inhabitants and others at Sydney.” Sydney Gazette August 24, 1806

To ease the chaos and regulate trade activity, Governor Bligh announced a dedicated marketplace on High Street (now George Street) near the southern end of today’s Rocks area:

“It is ordered, that in future no Purchase shall be made until every thing is landed at the place now appointed ; and that the Market shall not be considered to be opened until Seven o’Clock in the Morning. The said Market Place shall extend from the end Paling of Daniel McKay’s Garden, in the middle of High-street towards the Parade.”

Sydney Gazette, August 24, 1806

Plan of the town of Sydney in New South Wales (detail). James Meehan, assistant surveyor of Lands by order of His Excellency Governor Bligh, 13th. October 1807. The 1806 market place is shown at the left of lots 71 – 73. The ‘Old Parade’ ground is left of lots 13-14.

A moveable feast

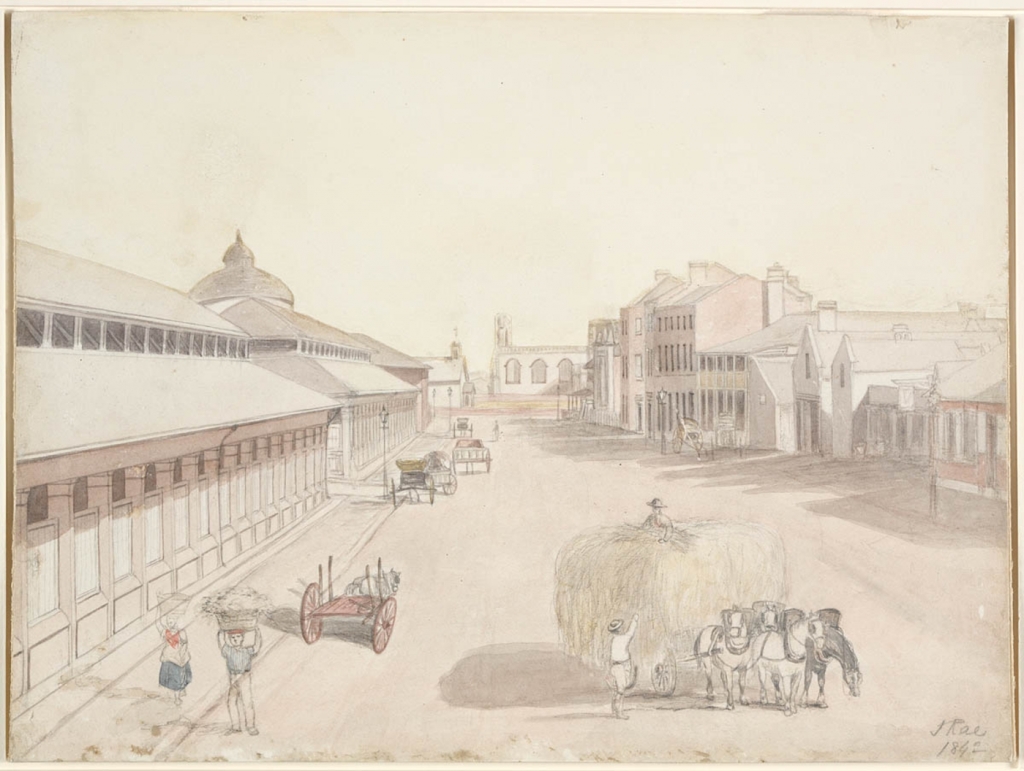

By 1809 another move became necessary, this time onto the Old Parade Grounds on the corner of George and Grosvenor Streets. According to Michael Christie, author of The Sydney Markets 1788-1988, “the market was both the economic and the social hub of the colony”, seen by observers as “a cross between the rural markets of Ireland and England and the flea markets of cockney London.” [5]

York Street, the Markets, [St Andrew’s] Cathedral and Corporation Offices, 1842. John Rae. © State Library of NSW. DG SV*/SpColl/Rae/2. The market buildings occupy the two blocks on the left. By 1842 the original Macquarie period domed building is now a Police Office and Courtrooms.

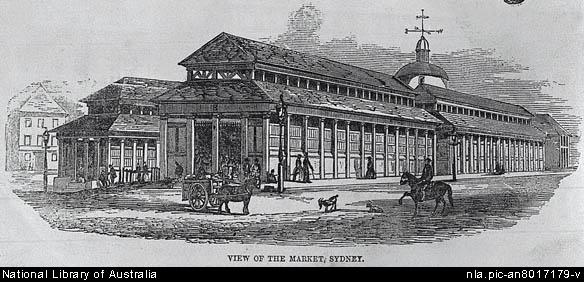

View of the market, Sydney. Walter G. Mason. [Sydney : J.R. Clarke, 1857] National Library of Australia PIC Volume 6A #S1258

Food glorious food

In spite of all their noise, mess and danger markets brought something vital to a place; they were (and remain) about food. Joseph Fowles described the Sydney market in 1848:

“they consist of four separate buildings, each about two hundred feet long, by thirty in width, and divided into stalls for the sale of the various kinds of produce; the first in York-street is used for the sale of meat, poultry, eggs, butter, cheese, &c., and the next for fruit and vegetables, those on the side of George-street, for wholesale dealers.” [4]

A social hub

Copy of a sketch of the Queen Victoria Markets Building labelled “The new city markets” looking SE from the corner of York Street and Market Street towards the Town Hall. © State Archives Office SRC10890

In Sydney “The economic boom of the 1800s and the increasing grandeur of new [city] buildings in the [mid-century] highlighted the shabbiness of the old George Street market.” [6] The newly formed Corporation of Sydney (1842), always with an eye to trends back in Britain, finally agreed that the George Street markets, along with the original domed courthouse building, had to make way for a far grander central marketplace which would occupy the entire block bounded by George, York, Druitt and Market Streets.

Construction on an extravagant ‘American Romanesque’ building – known simply today as ‘the QVB’ (shown above) – began in 1893, with Sydney now following the trend where, in the townscapes of the old and new worlds, “the public market had joined the church and the town hall as an idealized institution” [7]. The QVB would become a prominent neighbour to St Andrew’s Cathedral and the Sydney Town Hall on George Street. Sporting two levels of upmarket shops, it relegated the fresh food market stalls to the basement, well out of view of the more stylish upper floors.

Interior view from the upper (retail) level of the Queen Victoria Building immediately prior to its opening, 1898. © City of Sydney Archives.

Striking similarities

An early image of the QVB’s original interior from 1898 (shown above) immediately recalls the Leadenhall Market (shown above, at top), evidently as much a template for a ‘proper’ marketplace as it was for George Worgan and his peers a 110 years earlier.

But despite its architectural glory, the QVB became in economic terms a dismal failure. By the time it was built in 1898 Sydney was in recession, and the City Council made a grave error in seeking to encourage more refined retail activity and down-play the more-common food-focused market activity.[8] For subsequent decades the building was under constant threat of demolition.

‘Royal Clock, QVB, 2018’ via wikicommons.: Bahnfrend [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Today’s more cosmopolitan generations of Sydneysiders continue to be attracted to markets: ‘places’ that are diverse and inviting, continually evolving to suit local environments. And just as Leadenhall Market has satisfied the needs of countless generations in urban London, Sydney’s QVB has adapted to various changes in Sydney’s social history.

About the author:

The latest to join us here at C&C as a guest blogger, Heather Hunwick is an Honorary Research Associate at The University of Western Australia, and the author of The Food and Drink of Sydney: A History, published in 2018.

References

[1] George Bouchier Worgan, Letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12-18 June 1788. Includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788-July 1788.” ML, Safe 1/114, 36

[2] Heather Hunwick, The Food and Drink of Sydney: A History (Lantham: Roman and Littlefield, 2018)

[3] David Collins. An account of the English colony in New South Wales: With remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners, &c. of the native inhabitants of that country. To which are added, some particulars of New Zealand. Compiled, by permission, from the MSS of Lieutenant-Governor King by David Collins. 1798, London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies. May and December 1792.

[4] Joseph Fowles, Sydney in 1848. (Facsimile edition, Ure Smith, The National Trust of Australia (NSW). 1962, p.68

[5] Michael Christie, The Sydney Markets 1788-1988 (Sydney, The Sydney Market Authority, 1988), p.39

[6] Heather Hunwick, The Food and Drink of Sydney: A History (Lantham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2018), p.92

[7] James Schmiechen and Kenneth Carls, The British Market Hall: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999) p.48

[8] Heather Hunwick, The Food and Drink of Sydney: A History (Lantham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2018), p.93