The dining rooms that visitors experience at our properties are very different: some are relatively intact, some are complete recreations, while some are evocative interpretations. Today I’m looking at the dining room at Elizabeth Farm, and how it was known by the Macarthurs, by the 20th century Swann family, and how we experience it today.

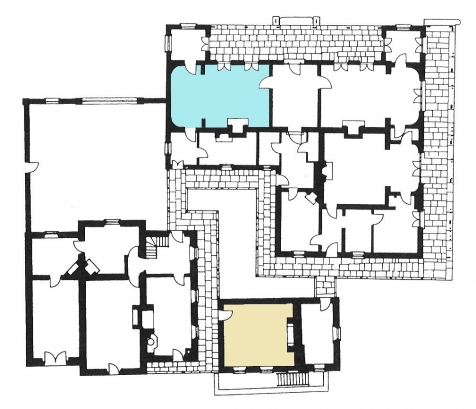

The dining room at Elizabeth Farm is one of the house’s 2 main reception rooms. Common to symmetrical Georgian design, it sits on one side of the central vestibule, opposite the drawing room. Albeit a grander scale the same arrangement is at Elizabeth Bay House.

Elizabeth Farm’s dining room is marked in blue. The kitchen is in yellow.

The Macarthurs’ dining room

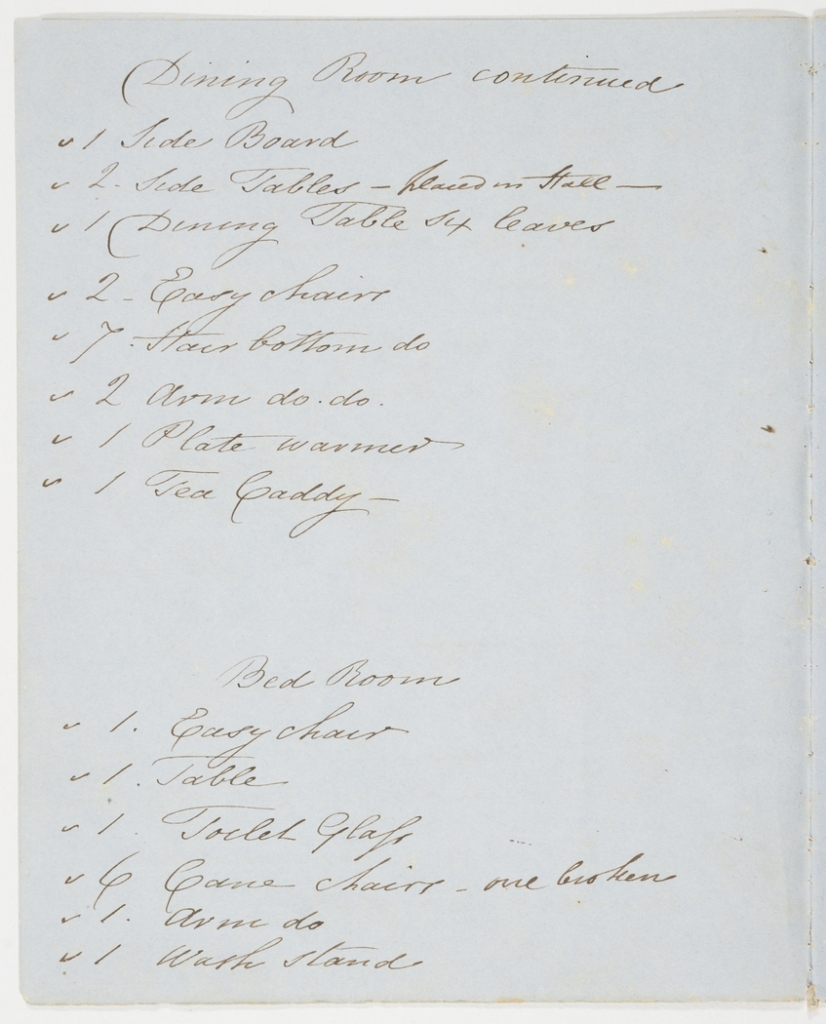

Sadly we have no views of the dining room at Elizabeth Farm during the Macarthur period. This is unusual as sketching and painting interiors was then a very popular pastime. I suspect that numerous drawings were done, but have since been lost. We also don’t have any inventories from the early period, instead relying on mentions in letters and a list drawn up in 1854 [2], 4 years after the death of Elizabeth Macarthur, at the request of her son Edward who had inherited the house and its contents from his father in 1834 – Elizabeth merely had a lifetime’s occupancy and use of the contents.

The list is short, and reflects a house between occupants – Edwards’s sister Emmeline and her husband Henry Parker who had lived there for 4 years after her mothers death had just moved out. It is likely that much of what we see recorded was there at the time of Elizabeth’s death, but it is a pale reflection of the house as it would have been when fully furnished. None of the standard dining ware or silver plate is mentioned.

1 print Queen Victoria removed by order of Colonel Macarthur

1 do. [short for ‘ditto’, ie also a print] Marquis Cholmondeley [either the 1st or 2nd Marquess Cholmondeley] removed by order of Colonel Macarthur

1 side board

2 side tables placed in hall

1 dining table four leaves

2 easy chairs

7 hair bottom [ie horsehair upholstery or horse hair stuffed] do

2 arm do. do. [ie armchairs, horse hair as above]

1 plate warmer

1 tea caddy

Dining room inventory. Sir Edward Macarthur catalogues of furniture and library at Elizabeth Farm 1854. ML SLNSW A 2919 / Item 4

Dining room inventory. Sir Edward Macarthur catalogues of furniture and library at Elizabeth Farm 1854. ML SLNSW A 2919 / Item 4

A lucky escape

The dining room at Elizabeth Farm in 1926. Photographer E.G. Shaw. Mitchell Library, SLNSW

This photograph dates to 1926, 22 years after William and Elizabeth Swann family had bought the property. We’re indebted to the Swanns as they ensured the house’s survival. If you look at the back of the dining room alcove, just to the right of the sideboard-dresser, you can see a large crack: Elizabeth Farm is built on highly reactive clay foundation which causes considerable structural movement. The west end of the building, under this wall, was actually completely underpinned after its acquisition by the NSW State Government to try and control this. Margaret Swann later described the house’s forlorn condition in 1904, and its lucky escape from demolition:

The house then, at first glance, appeared to be a veritable ruin. There were many broken panes of glass, partially covered with torn pieces of hessian, the papers hung from the walls in melancholy festoons, cobwebs were draped over everything, and altogether the place very uninviting.

In 1904 my father purchased the house and 6 acres of land surrounding it. A member of the syndicate who sold it, told him that they were asking the price of the land only, as they recognised that the house was too old to be considered an asset; the only use for the house, they said was to pull it down and build a cottage with any of the material that might be insufficiently good condition. This, he said, they intended to do, unless they soon found a buyer. However, my father had some knowledge of architecture, and he saw that the foundations, walls and roofs were perfectly sound and strong; he also recognised that it would be pure vandalism to destroy such a historic building unnecessarily, so having purchased it, he immediately proceeded to have it thoroughly cleansed, disinfected and repaired, and we moved into it on 30th of December, 1905. [1]

The Swanns’ dining room in 1926

In the photograph the Swanns’ dining room room has a patterned linoleum floor and seems to be lit by gas lights with inverted burner fittings – though the jury is still out on this one. The mirror of the sideboard-dresser, which is ornamented with a silver tea set, china teapot, toast rack and egg cruet – reflects a full bookcase on the opposite wall, a reminder of the value the Swanns placed on their children’s education. Spare dining chairs are arranged against the walls while others are casually pulled out for the photograph, and what may be a serving table or chiffonier sits between the French doors on the extreme right. Cane easy chairs sit before the fireplace. The numerous pictures hang from what are possibly much earlier hanging points, which suggests where the Macarthurs had hung their own pictures. I cant quite make out the flowers in the table vases, but I think they’re a mix of hellebore, ranunculas, anemone and gum leaves. To accommodate the angle of the photograph the table has been pushed slightly into the alcove. The original bell-pulls likely no longer function, as a hand-bell sits on the sideboard.

In 1982…

The Trustees of the Historic Houses Trust meeting in the Elizabeth Farm dining room during conservation works, 16 April 1982. Photo Peter Stanbury (c) Sydney Living Museums

… it was a very different scene as restoration work was in full swing. In 1968 the house had been sold by the last Swann sisters to the newly formed Elizabeth Farm Museum Trust, who intended to restore the house. Unfortunately it proved too great a task and in 1977, somewhat ironically again in a very poor state, it was transferred to the NSW Heritage Council. A program of restoration began – which unfortunately did much to erase the tangible evidence of the Swanns, though in many ways the actual survival of the house is their legacy. Elizabeth Farm was then listed under the new ‘New South Wales Heritage Act’- as “Conservation order no. 1.” The house was then transferred to the newly formed Historic Houses Trust of NSW (now Sydney Living Museums), and opened as a house museum in 1984.

The room today

The dining room at Elizabeth Farm set for breakfast. Copyright Paolo Busato

Today visitors to Elizabeth Farm enter not a recreation of the Macarthur’s dining room but what I call an ‘evocation’, a representation based on the 1854 inventory. We leave it to the visitors to ‘fill in the gaps’ using their own imagination. Its a piece of theater. The large portrait of John Macarthur,a copy of the State Library portrait, stares down from over the chimney-piece, and a copy of Conrad martens view of the house from the Parramatta river [the view seen below was taken before a rearrangement of the artworks]. Together they pose the question of ‘image’: who were the Macarthurs? What do we think of them, what did their contemporaries think of them, and what did they think of themselves? Its an appropriate question for the most ‘public’ room of the house. The sideboard is a copy of the sideboard from Belgenny that I discussed a few weeks ago. Chairs sit around the walls ready for use. The table is an extension table, reflecting the table with ‘four leaves’ in the inventory; originally a Georgian D-end table would have been used. Flanked by serving tables the chimney-piece with its mismatched top is most likely a later replacement, perhaps late 19th century.

The dining room at Elizabeth Farm set for breakfast in 2014. Photograph (c) Paolo Busato Historic Houses Trust of NSW

Periodically we run ‘snapshot’ and theme tours that examine dining at the house, and we set the table. Coming up we have the ‘Spring Harvest’ festival where, along with carefully chosen food stalls and talks with Jacqui and myself, I’ll also be running demonstrations of dinner and dessert settings ala 1820s style. Perhaps I’ll see you there.

Second helpings

[1] Miss [Margaret] Swann, ‘Elizabeth Farm House 1793-1914’ in Parramatta and District Historical Society; Journal and Proceedings. Vol. 1. The Cumberland Argus Ltd., Parramatta 1918.

Discover more about Elizabeth Farm’s lucky escape from demolition here.

[2] After Elizabeth Macarthur’s death in 1850 her daughter and son-in-law, Emmeline and Henry Parker, continued to live at Elizabeth Farm for four years. Edward Macarthur, who had inherited the estate on his father’s death, lived in England. In the early 1850s he appointed as his agent Henry’ Curzon AlIport. William Allport succeeded his father as agent in 1854 and the Allport family then lived in the house until 1863, when William Allport was dismissed and Edward Macarthur’s nephew, James Macarthur Bowman, became his agent. [Excerpt, draft text for a guidebook by Dr James Broadbent]

The inventory of Elizabeth Farm in 1854 – titled “Catalogue of furniture at Elizabeth Farm made May 1854 by H. C. Allport and left in his care by Coll. [Colonel] Macarthur”- is online at the State Library of NSW.