My research into domestic life in regional Australia has led me to some personal memoirs of late, including Barcoo Rot and other recollections, a transcript of oral histories taken from Jean Thomas (nee Bertram), about her early life in remote Queensland and later, northern Tasmania in the early 1900s.

‘Then, and only then, could we move onto something sweet’

It is a self-published book, so not in wide circulation, but it was recommended it to me by a relative of Jean’s, as it contains many references to food – as any good memoir does! (Please note however, that the images used on this post are not of the Thomas or Bertram family, but hopefully reflect the times.)

Like much conversation around tea, it is often not the tea itself that is the focus, but the ceremonial and social proceedings around the taking of tea that shine.

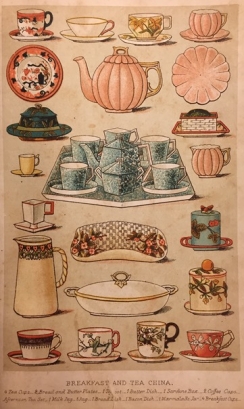

Breakfast and tea china in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s book of household management, Ward, Lock & Co., c1880. Sydney Living Museums R89/80

‘The rules had been set a long time …’

Ladies in the rural Northdown community (about 10 kms east of Devenport) maintained social contact with friends and extended family through ‘a round of tea parties’ on Wednesday afternoons. Jean explains the ritual (take particular note of the favoured sandwich filling and the way the sponge cake was cut…):

The rules had been set a long time… everyone would have to take their turn…

The tea parties commenced at 3.30 sharp, always on Wednesday afternoons…

The hostess’s husband would remain present until he had drunk one cup of tea and would then retire to leave the ladies discussing important matters…The ritual of the food served and the order in which it was served was important and is interesting.

First of all there was plain bread and butter, thinly sliced, always white, and thinly spread. One could comment on the quality of the butter, it was all home made, and also comment about the bread if that was also home-made.

The bread and butter was followed by cucumber or tomato sandwiches in season.

Next came sandwiches with a meat filling. If a sheep had been killed the previous day, as was often the case, brain sandwiches were preferred. They were a delicacy and had to be enjoyed.

Some sort of dry biscuit, or small cakes with currants or raisins, such as a rock cake, were optional next.

Then, and only then, could one move on to something sweet.

Sandwiches, with a filing of perhaps raspberry, blackcurrant jelly, or even fig jam came next. Jams and preserved were made by everyone.

Scones straight from the oven came next, with butter only!

They were followed by a tart or slice with chocolate or sugar-icing.

Only then could you have what you were waiting for – a slice of fruit cake, thinly cut.

Finally, came the piece de resistence, the sponge cake. It would have been made by the maid or the cook. All the cousins were expected to ooh and aah over its quality and presentation, and they always did. It would be decorated with passion-fruit icing, with a circular slice cut in the middle, kept for the boss, and equal segments already cut, one for each guest.

After tea, as guests were leaving, they would be shown around the garden, and would take, with permission, any cuttings that took their fancy, and collect any pot plants they might have arranged to exchange.

The ritual might be repeated the following week, elsewhere.

Barcoo Rot and other recollections of Jean Thomas (nee Bertram). Edited by Bertram Thomas from an oral history transcript 1982. B.M. Thomas. 2005.

‘At home’

These parties were typical of domestic social gatherings, particularly in rural areas, in times before sociable cafes were standard features of small towns. The Thorburn sisters entertained in similar fashion ‘At Home’ on Monday afternoons, which we will talk more about next week.