When I was a child my dad would confuse me by asking “do you say the yolk of an egg is white or are white?” But it is their yin-yang, rich-light; oily-dry duality that makes eggs such a versatile food. While the sun shines in the yolk it is the whites that bring light to many a dish, including omlets, meringues and snows. Best known to all Australians must be the iconic pavlova which has long been the topic of Antipodean debate about who ‘invented’ the pavlova as we know it, but we’re wise enough to steer clear of such competitive controversy and celebrate some other light white wonders this week!

Not all sweetness and light

It isn’t all sweetness and light – egg white had other practical applications in the kitchen. Lightly whipped egg white was painted onto ceramic bottles and jars to seal their porosity. Egg whites were also used for clarifying liquids, an art still used today to refine consomme and some wines. It was also used to clarify the meat-based stocks used to make jelly or gelatin (which you can see in this Eat your history calf’s feet jelly video). Mrs Beeton explains the science behind the art with her particular didactic nineteenth-century style flourish:

1387. THE WHITE OF EGGS is perhaps the best substance that can be employed in clarifying jelly, as well as some other fluids, for the reason that when albumen (and the white of eggs is nearly pure albumen) is put into a liquid that is muddy, from substances suspended in it, on boiling the liquid, the albumen coagulates in a flocculent manner, and, entangling with it the impurities, rises with them to the surface as a scum, or sinks to the bottom, according to their weight.

Techno-free technique

Whipping egg whites is quite an art too, even these days. The secret is to make sure all your equipment is absolutely squeaky clean, as any slight trace of oil will prevent the egg forming stiff peaks, essential for lightness and volume in meringues, mousses, souffles or delicate sponge cakes. We now have the benefit of electric beaters or high powered ‘chef’s’ or ‘kitchen aids’ to whip eggs, but it wasn’t always that way. Cooks would use bundles of sticks as whisks or even their fingers, with recipes saying to beat eggs for up to an hour! Aunt Kate (Jessie Catherine Thorburn 1857 – 1945) at Meroogal employed a now-old fashioned but ‘tried and true’ method of whipping egg whites for the family’s signature Meroogal sponge cake, which you can see being made in this video, whipping the required six egg whites on a large flat dinner plate using a table knife. Kate would whip the whites for precisely twenty minutes to achieve the correct volume. We challenge you to do this stamina test for your next sponge!

Lost favourites

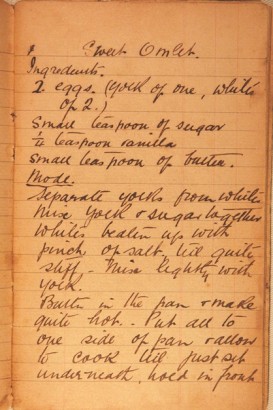

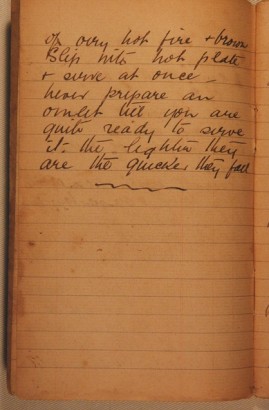

We’ve talked about various ‘snows’ in this blog – with recipes for sago snow and apple snow. Another sweet treat that appears on nineteenth-century menus, often as an after dinner extra, is a ‘sweet omlet’ easily prepared and served in a jiffy. It appears to have been a family favourite in the Meroogal household, with this recipe recorded in one of their manuscript cookery books in 1908. It comes with a final note which inspired today’s blogpost title: ‘Never prepare an omlet till you are quite ready to serve it. The lighter they are the quicker they fall‘. It’s quite a useful recipe for a household where eggs are always in supply, which would have been the case in many homes, large and small, that kept their own chooks. They can be served plain, dusted with icing sugar or topped with jam or syrup. Ease up on the sugar if you’re going to serve them with a sweet topping. It’s what my mother would have called a ‘poor man’s’ souffle.

Meroogal manuscript recipe for sweet omlet (first page). Sydney Living Museums

Sweet omlet, Meroogal style

Ingredients

- 2 eggs, yolk of one, whites of two.

- 1/2 teaspoon caster sugar

- 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1 teaspoon butter

- icing sugar or sweet syrup, to serve

Note

This recipe comes with a cautionary note: omlets must be made just before serving, 'the lighter they are the quicker they fall'. The omlet will puff up as it cooks, but will deflate as it cools, so pay heed to the authors advice!

Directions

| Preheat grill. Separate yolks from whites. Mix the yolk from one egg with the sugar until light and frothy. Beat whites up with a pinch of salt in a very clean bowl until quite stiff. Fold lightly through the yolk. Melt butter in a small frying pan heat until it starts to foam. Pour in egg mixture and cook until it has just set underneath. Remove from heat and hold the pan under the grill to set the top. Slip onto a warmed plate and dust with icing sugar, if using. Serve at once or it will lose its puffy lightness. If serving with syrup, serve in an accompanying jug. | |

Snowy peaks

Egg whites are key of course to meringues and macaroons (macarons these days), but they really came into their own in the domestic baking repertoire with the arrival of ‘modern’ technologies including gas ovens with controllable temperatures, and – wait for it! – the rotary beater! (Yentsch, 2012). Combined, these culinary revelations allowed housewives to create large scale meringue cakes (pavlova) and meringue-topped pies – the lemon meringue pie probably the only true survivor in Australia. Meringue ‘pies’ were also a practical way to make use of the whole egg, the yolks used in rich fillings and the whites adding contrasting colour and texture.

Whimsical treats

Antonine Careme, chef to Prince Regent at the Brighton Pavilion created Meringue des pommies en harrison, a whimsical dessert requiring forty apples blanketed in whipped sweetened egg white and decorated in the form a hedgehog (harrison). It was much copied in cookbooks and is still fun to make today, especially if you want a children’s treat, albeit in a much simplified and more manageable version.

Apple hedgehogs

Ingredients

- 6 firm apples, eg granny smith, gala, pink lady (not too large)

- 12 pitted dates

- 3 egg whites

- 3/4 cups sugar

- 1 teaspoon cornflour

- sliced or slivered almonds

- 12 currants or small sultanas

Note

French chef Antonine Careme is said to have created meringue des pommes en herrison 200 odd years ago. It was served at the Brighton Pavilion, the Prince Regent’s palace, in 1817, which made it highly fashionable. It was originally made using 40 whole apples, peeled, cored, stuffed and then piled into a big mound on a dish. Any gaps were filled with a blend of pureed apple ‘marmalade’ and apricot jam. The apples were then blanketed with meringue, and studded with almond or pistachio slivers, to resemble hedgehog quills or spines. This is a much simplified version, echoing the original, yet still delicious and delightful – especially for children, who will enjoy the whimsy.

Directions

| Preheat oven to 180°C and line a baking tray with silicon paper. Peel and core apples, halve across the middle (ie horizontally) and place each half on the baking tray, leaving a good 5 or 6 centimetres between each one. Press two dates into the centre of each apple. | |

| Using electric beaters, whip egg whites and 1/4 cup of the sugar in a large bowl until egg becomes thick, white and glossy. Gradually add remaining sugar and cornflour, and beat until stiff and peaks hold their form. Spoon meringue mixture over apples, to form at least 1/2-centimetre coating, taking care not to leave any gaps. Insert almond slices into the meringue to mimic spines or quills. Place in oven on lowest rack, reduce heat to 140°C (120°C fan-forced) and bake for 15–20 minutes, checking occasionally that meringue is not discolouring and almonds are not browning too quickly. If colouring, place a solid tray on the rack above to minimise exposure to radiant heat, or prop the oven door open just a little to reduce heat slightly. Use a fine skewer to check that meringue has cooked and apples have softened but still hold their form. Remove from oven and gently press currants or sultanas into position as eyes, and allow hedgehogs to cool (do not refrigerate or meringue will become tacky). Once completely cooled, transfer to a sealed container or a platter covered with a cloth. Serve within 24 hours. | |

References and further reading: Anne Yentsch. ‘Lessons from archaeology and anthropology for New England cookbooks: pies and puddings’. 2012.

Print recipe

Print recipe