As we delight in the edible joys on offer at our annual Christmas artisan food fare at Hyde Park barracks, it is interesting to reflect on what our colonial counterparts were putting on their tables for Christmas.

Festive fare

Certainly the obligatory turkey, ham and festive plum pudding may have been front and centre on the colonial Christmas table, but they were quite often just part of a broader repertoire of festive foods available in nineteenth-century Sydney. In fact, roast turkey and leg ham – often a ‘York’ ham (see below) – were not reserved for Christmas only, but standard celebratory fare for any special occasion, being served at formal dinners, banquets and balls well into the 20th century.

It is interesting that it is these three ‘icons’ that have survived as the traditional Christmas day foods, albeit being eclipsed in some Australian households for seafood and berry-laden pavlova.

!['Supper table' (detail) in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Beeton's every-day cookery and housekeeping book, Ward, Lock & Co., London, [ca.1895]. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2016/12/x1895-ham-zoom-COL_CSLRC_recno1299_0111.jpg.pagespeed.ic.9c4lbXJRIo.jpg)

York ham

The York ham was regraded superior to ordinary leg hams, being larger and having a particular pear-shape that carved well at the table. Prized for their mild delicate flavour and moist texture, York hams were cured with salt, saltpetre and sugar, and rather than being smoked, were left to dry-age for 2 to 3 weeks, then packed in straw for up to twelve months, according to Eliza Acton in 1845. They could then be gently boiled or baked, after being soaked for 12 hours or more, to remove excess salt. The skin would be decoratively patterned and scored, the baked hams glazed with mustard, honey and spices as we might still do today.

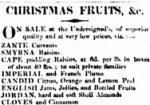

Christmas markets 1841

Local market reports from December 1841 in the Sydney Gazette boast an array of meats, poultry, vegetables and fruits. Ham, pork ‘roasters’ and veal appear to be the meats of choice but poultry was especially prized, and the turkeys enviable, according to the journalist:

The lovers of Christmas good cheer may expect poultry in beautiful order for this yearly festival… Some of the turkeys yesterday exposed for sale might raise envy in the heart of an English farmer’s dame.

Geese, 7s-10s each; turkeys, 8s-16s each; fowls 4s 6d-5s per pair; game ducks 7s-8s each; wild ditto, 4s 6d-5s each; pigeons, 3s per pair; rabbits, 5s 6d-7s.

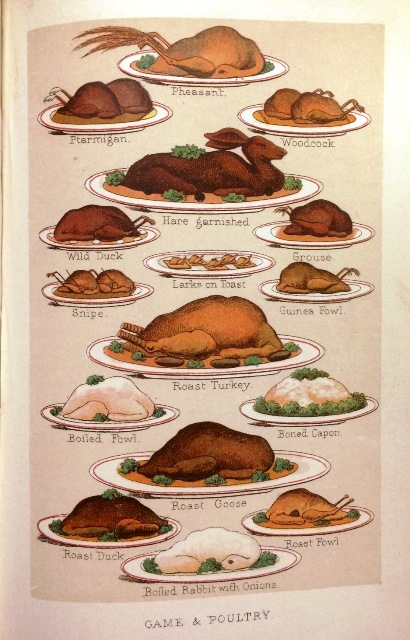

Poultry and game colour plate from Beeton’s book of household management circa 1880s. Rouse Hill House and Farm collection. © Sydney Living Museums

A cornucopia

Fresh garden produce was ‘plentiful and of very fine description’. In addition to the usual suspects – cabbages (red and regular), onions, turnips and carrots there was vegetable marrow (which are like very large zucchini), fresh peas, broccoli, French beans, broad beans and asparagus. Cooling salads spring to mind with lettuces, cucumbers and radishes.

Cherries, plums and apricots ‘covered with the bloom of the garden decked several stalls’, oranges were plentiful, loquats were sold by the quart but bananas were scarce, selling for 6d each.

Mince pies, from Beeton’s book of household management, 1863. Rouse Hill House and Farm collection.

A range of cheeses, locally produced and imported were also advertised – Cheshire, Dutch, and ‘pineapple‘; fresh butter came at a whopping 2s 6d – 3s – that is, the same price as one fresh chicken. Eggs were between 1s 3d and 1s 6d per dozen and honey was 2s per pound.

Patisseries advertised pies and pastries, grocers an array of dried fruits, nuts, spices, preserves and chutneys, sauces and condiments to complement every meal. Despite purchasing over 70 kilos of dried fruit in December 1844, the Wentworth’s bought mince pies from a local pastry shop. Perhaps pastry was beyond their cook’s skill set.

Eating well

Clearly, for those who could afford it, the range of food on offer in the colony was extensive – far more-so than we often give our forefathers credit for. And even those with modest means might have the advantage of their own chickens and eggs, locally caught fish or oysters, and produce from their kitchen gardens.

What will you be serving this Christmas?