Its been a long time since we posted twice a week, but we’ve got so much coming up over the next few months that I thought we could have a second helping of artichokes.

Artichoke plant with three heads. Photo (c) Scott Hill

Last week Jacqui wrote about the artichoke, which is in high season right now. As inevitably happens a long convoluted discussion (seriously, the conversations we have!) started on the artichoke in the early colonial gardens – a date long before the 1950s when many people think they were introduced.

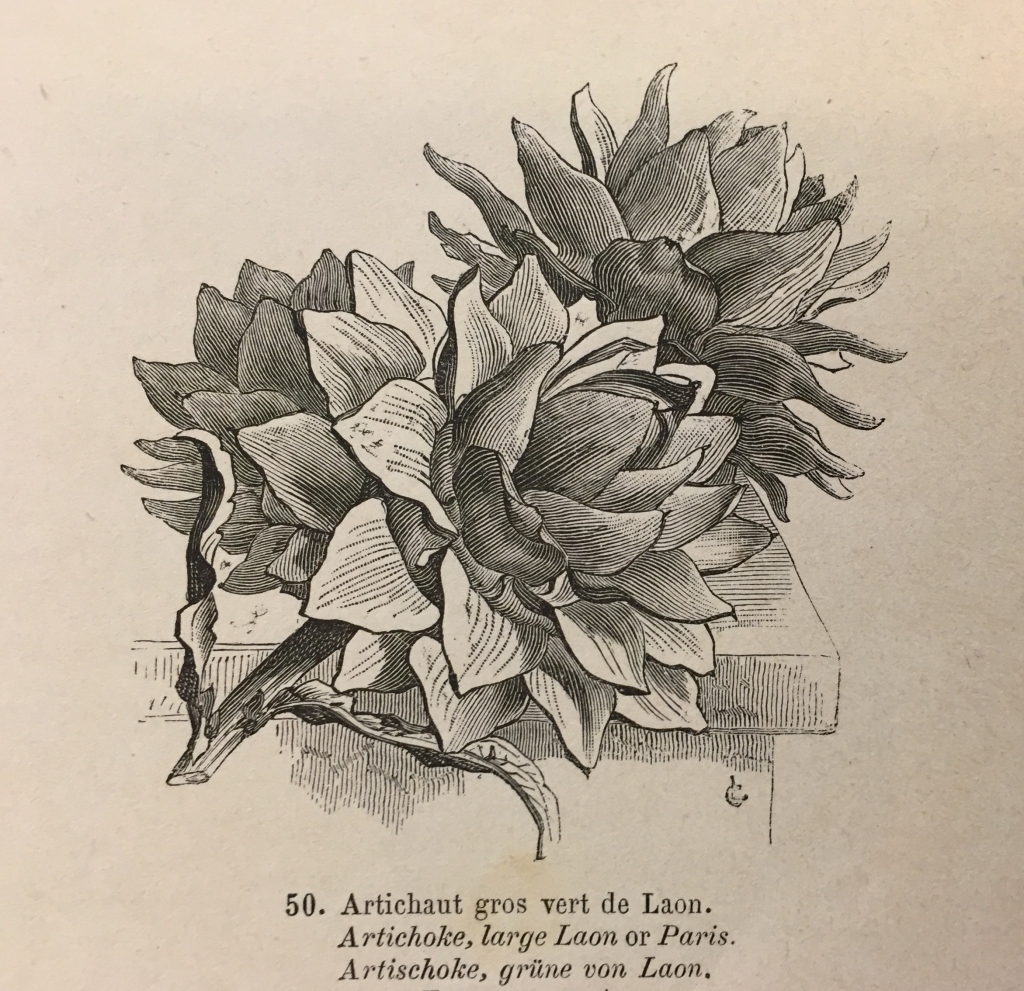

‘Artichaut gros vert de Laon’. Album de cliches; Paris, Vilmorin-Andrieux & Co., 1888. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection.

Early 19th century English (the then catch all-phrase meaning ‘British’) cookbooks routinely contained artichoke recipes, and writers such as John Claudius Loudon described its cultivation, but also gave tips on its use in cooking (suggesting they weren’t all that widespread on English tables):

The flower-heads in an immature state contain the part used, which is the fleshy receptacle, commonly called the bottom, freed from the bristles and seed down, vulgarly called the choke, and the talus or lower part of the leaves of the calyx. In France, the bottoms are very commonly fried in paste, and they form a desirable ingredient in ragouts. They are occasionally used for pickling; and sometimes they are slowly dried and kept in bags for winter use. In France, the bottoms of young artichokes are frequently used in the raw state as a salad; thin slices are cut from the bottom with a scale or calyx leaf attached, by which the slice is lifted, and dipped in oil and vinegar before using. The chard of artichokes, or the tender central leaf-stalk blanched, is by some thought preferable to that of the cardoon. The flowers possess the quality of coagulating milk, and have sometimes been used in place of rennet. [1]

A writers to the colonial newspaper The Gazette in 1829 offered this useful advice as to cultivating artichokes:

Making the Heads of Artichokes grow LARGE.-An excellent method of increasing the size of artichokes is to split the stalk at the top in four parts, and to introduce through the cuts two small staes of wood placed across. This operation has been long practised in the south of France ; several gardeners in the neighbourhood of Brussels have adopted the same custom for several years past, and have obtained much larger artichokes than formerly. Care should be taken not to perform the operation until after the stalk of the artichoke has acquired its full height. [2]

Does anyone know the technique he described? Does it work?

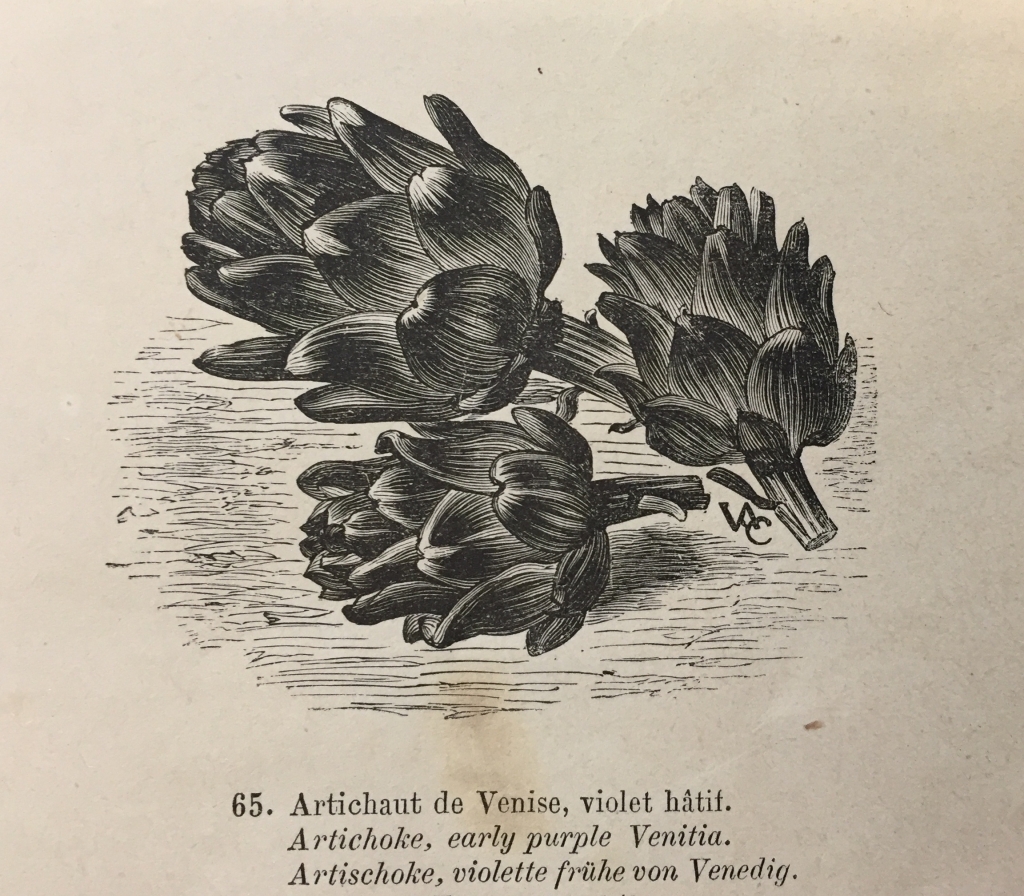

‘Artichaut de Venise violet hatif’. Album de cliches; Paris, Vilmorin-Andrieux & Co., 1888. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection.

Popularity?

But how widely were they being grown? In its ‘Weekly Calendar’ for Friday, 27 May 1831, The Australian advised it was time to transplant seedlings, but also commented on the vegetable as not being widely grown:

Early in June, it will be proper to sow turnips, carrots, peas, and beans; to transplant onions, schallots, leeks, artichokes, (an agreeable esculent, which, with celery, appears to be but very scantily cultivated,) and young fruit trees; and truss to vine-settings.

A clue also lies is in the weekly market reports, where grocery prices were published. In 1829 artichokes are listed at 3 pence a-piece. [2] This is pretty steep, which indicates they weren’t in the everyday shopping basket but more a luxury item, but still indicates they were being produced in enough quantities to be commercially available. A year later and the price still hovered around 3 pence, but dropped to 2 pence, possibly when the harvest was at its height. [4] By comparison, in the same week carrots were 3 pence a dozen, and radishes 1 penny a dozen. Jump to 1835 and they’re now being sold by the dozen – which suggests both an increase in production and popularity – for 1 shilling and 6 pence, so still 3p each. [5]

Artichoke plant. Photo (c) Scott Hill

“…some persons are fond of them”

Thomas Shepherd’s second lecture on gardening in the colony, delivered November 5th, 1834, also includes the cultivation of the artichoke, as well as cooking tips:

ARTICHOKES. -A moderately rich strong loam is the best suited for artichokes. Let it be trenched three spades deep, and dig in plenty of rotten manure at the time of trenching. Take slips or off setts from old plants, (if you have not got any, you can purchase them at a nursery), and plant them in rows six feet wide, and at four feet apart, plant from plant, in the row. Let three slips be planted in place of one, as just mentioned, about three feet apart, from June to September, and they will produce a good crop the first season, if irrigated in dry weather, afterwards let a moderate quantity of manure be dug in about them, in the months of May, June, or July, and at the time of digging, take all the off-setts from the stools except three, which must be left for a crop -and you will obtain as good artichokes as you could wish for. They succeed best upon a southerly aspect. They are very useful, and some persons are fond of them, if they are not too old, for a supper dish They are used with melted butler in England, and in Scotland with cream. The old artichokes are generally boiled well, and the bottoms are afterwards dried and hung up upon a string, and will keep a long time; they are used in soups by grating them to a powder.

Grated artichoke? Its not as odd as it sounds: think of grated, dried porcini mushrooms added to Italian recipes.

Globe artichoke head. Photo (c) Scott Hill

Notes

[1] John Claudius Loudon, Encyclopaedia of Gardening, London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1822

[2] Sydney Gazette, 12th December, 1829

[3] The Monitor, 23rd November, 1829

[4] ‘Thursdays Market’ in the Sydney Monitor, 13th November, 1830

[5] The Colonist, Thursday 5 November 1835

The engravings are from a fascinating book in the Caroline Simpson Library, a book of ‘cliches’ – ‘pictures’. The illustrations – from the ‘Album de cliches’ (Paris, Vilmorin-Andrieux & Co., 1888) – advertised engraved plates that could be bought ready made to use for illustrating new books. You’ll see more of them in the months to come.

And the fresh artichokes? These were growing in the St. Kilda, Melbourne, community garden, which I visited earlier this week.