Artichokes are in their prime at the moment. They are a member of the thistle family, and have been popular in the Mediterranean region since antiquity, but to many Australians they still seem very curious and foreign – partly because we’re not quite sure how to prepare and eat them. We’re more likely to buy their ‘hearts’ ready-pickled in brine or oil as an antipasto ingredient than cook them whole, which is a shame, because freshly cooked artichokes are a fun and highly sensorial food to eat – best eaten without cutlery and nibbled on rather than dined upon.

Artichokes in the kitchen garden, Commandant’s cottage, Port Arthur. Photo © Jacqui Newling

Old friends

Like eggplants and okra, ‘globe’ artichokes are among the vegetables that we associate with post-World War 2 migrants from southern Europe, but they were all here in the colony in the early 1800s. Artichokes are among the extensive list of plants brought to Australia on the First Fleet, though it is not clear whether they were the ‘globe’ thistle variety or the tubers we now refer to as Jerusalem artichokes. The globe artichoke is included in the list of ‘esculent vegetables and pott herbs cultivated in the Botanic Gardens’ in the 1820s. The eponymous font of knowledge for all things botanical, J C Loudon, wrote in 1822:

They are occasionally used for pickling; and sometimes they are slowly dried and kept in bags for winter use. In France, the bottoms of young artichokes are frequently used in the raw state as a salad; thin slices are cut from the bottom with a scale or calyx leaf attached, by which the slice is lifted, and dipped in oil and vinegar before using. [1]

Artichokes were being advertised for sale for twopence each in the Sydney Markets in springtime, 1830, making them something of a delicacy. Recipes for artichokes feature in colonial cookery books in the late 1800s and the turn of the 20th century but it appears that they were not ‘standard fare’ for all: in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1915 they were described as ‘a well known vegetable to some of us, to others an utterly strange one’ [2]. heirloom varieties of artichokes can be seen growing in heritage gardens including the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House, often with a tufty purple crown if left on the bush too long. Artichokes are now grown commercially for the retail market so easy to obtain.

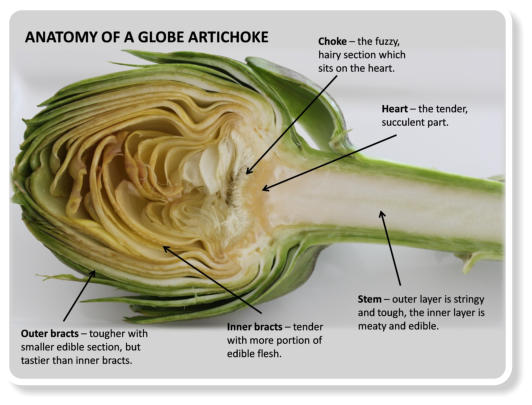

Anatomy of an artichoke. Image courtesy Josephine Mazza © R&J Mazza www.rjmazza.net.au

The ‘anatomy’ of the artichoke

The artichoke can be a little threatening to the uninitiated as they are not entirely edible – the outer leaves are tough and stringy, and even then it is only the base of the inner leaves that have any ‘meat’ on them; the fibrous choke itself is bitter and extremely unpleasant in the mouth and it all seems rather a lot of work to access the luscious heart within. To me however, they represent a food philosophy that says even the most unfriendly food source is worthy of a bit of ‘work’ to ensure it can be utilised – the olive is another example.

Artichoke halves © Jacqui Newling

A toothsome dish

Mrs Beeton (1861) gets my vote for simplicity and edibility – just boiling the artichokes until tender and serving them with the ultimate English finishing sauce, melted butter (I add herbs and lemon to temper the richness of plain melted butter – see recipe below). To eat them, you pluck each leaf from the artichoke, and holding it by its tip, dip the base of the leaf into the butter sauce. Shake off the excess and scrape the leaf between your teeth – the edible flesh is on the underside of the leaf, closest to the base of the leaf. Discard the rest of the leaf and continue until all the leaves are finished. There’s no double dipping – its a one-leaf at a time process. The soft, unctuous heart at the base of the globe is the reward, but remember to so discard the choke – unless you’re one of those people that needs to experience something before believing it’s no good. You can serve the artichokes on a central serving platter, cut in half like little hedgehogs or armadillos gathered around the dipping sauce, or served whole, lotus flower-like, in individual bowls, for people to dismantle themselves.

Spent artichoke leaves Photo © Jacqui Newling

Continental styles

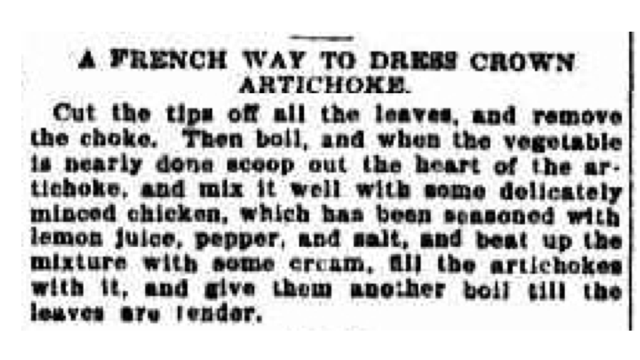

Another option given by Mrs Beeton was to quarter them once boiled, remove the chokes, then batter and fry them in hot lard or dripping. Served with – you guessed it – plain melted butter. Her French variant was to add herbs and butter into the cooking water and the Italian way was to serve them with a rich and thick mushroom sauce. Southern Italians go to great effort making specially seasoned stuffings with breadcrumbs, herbs, anchovies and Parmesan (which is quite a bit of work!). Although he was a great advocate of Mediterranean-style living, Phillip Muskett’s Art of living in Australia (1893) recommends artichokes be simmered for an hour with a little milk added to the cooking water, from which you reserve half a pint (2 cups) to make a white sauce to pour over the artichokes when serving. With no instructions to cut them up or remove the choke this conjures a rather messy and awkward dish to eat. The recipe below, published in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1905 makes them something of a meal, filled with a creamy lemony minced chicken.

‘Domestic Hints’ Sydney Morning Herald, November 15, 1905 via Trove

A global view

To clarify, we’re talking the ‘thistle’, ‘globe’ or ‘crown’ variety of artichokes rather than the tuberous Jerusalem artichokes, which burst onto the food scene a few years back, but were also popular in the 1800s (the subject of a future story). The thistle artichoke is related to the cardoon thistle, which also grows in our kitchen gardens, and has its own characteristics and culinary uses, primarily from its stems (another story to look out for in the near future). They typify so many vegetable varieties that were grown in Australia in the colonial period yet somehow dropped from our menus in the mid 1900s – possibly due to patriotic ‘Empire’ drives during the 1930s Depression and Second World War periods. Claims such as ‘the Italians introduced the artichoke to Australia in the 1940’s’ persist, and to their credit, revived and popularised many of the ‘forgotten’ less common vegetables. Its wonderful to see them being appreciated more widely by consumers today.

Artichokes with lemon and herbed butter sauce

Ingredients

- 4 globe artichokes

- 100g butter

- teaspoon dried mixed herbs or herbs de Provence

- pinch ground nutmeg

- 1/4 teaspoon ground white pepper, or to taste

- zest and strained juice of a lemon

Note

For this recipe I've taken the liberty of being a little bit French by adding herbs to the butter sauce, and lemon juice and zest to help cut the richness of the butter.

Mrs Beeton suggests adding a couple of teaspoons of bicarbonate of soda to the cooking water to help prevent the artichokes' vibrant green colour from fading as they cook. This was a common 'old housewife's' trick which is now much maligned, but it does work!

Directions

| Bring a large pot of salted water to the boil (about half a teaspoon of salt per artichoke). Meanwhile, cut off the stems close to the base of the globe and remove the tougher lowest row or two of leaves. If the leaf tips are pointy and hard, trim off the points. Put the artichokes into the water, return to the boil then keep on a steady simmer for 25–30 minutes or until centres are tender and leaves come away easily when gently pulled. Meanwhile, prepare the butter sauce. Put 3 cm of water into a saucepan and bring to the boil. Put the butter, lemon zest, herbs, nutmeg and pepper into a heatproof jug or deep bowl and stand it in the saucepan. Turn off the heat and stir the butter gently for 5 minutes, or until the butter has melted. Add the lemon juice and a good pinch of salt, or to taste. Check the balance of flavours and adjust accordingly, then leave the jug in the warm water while the artichokes cook, to allow the flavours to develop. Using tongs or a slotted spoon, remove the artichokes from the saucepan and allow them to drain in a colander for a minute or two, heads down. Serve in individual bowls, with a side plate to receive the spent leaves. To eat, pluck each leaf from the artichoke from its tip, dip the base of the leaf into the melted butter and scrape the leaf between your teeth – the edible flesh is on the underside of the leaf closest to the base of the leaf. Discard the rest of the leaf and continue until all the leaves are finished. The soft, unctuous heart is the reward, but the fibrous 'choke' at the base of the globe is coarse and bitter, so discard it without being tempted to try it – unless you're one of those people who needs to experience something before believing. | |

Sources and further reading:

[1] J C Loudon Encyclopaedia of Gardening, London, Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1822

[2] Penelope’s weekly notes. Sydney Morning Herald (via Trove) October 13 1915

Victorian producer R & J Mazza has lots of information and recipes on their website. Special thanks to Josephine Mazza for providing her ‘anatomy’ diagram.

The colonial plants database, Sydney Living Museums.

Print recipe

Print recipe