While we’ve looked at the more well known cookbooks in the Rouse Hill collection, from Mrs Beeton through to the Commonsense Cookery Book, there are a host of others.

If you’ve bought a new cooking appliance you probably found a booklet of recipes included, intended to showcase the virtues and teach you the tricks of the new purchase. “My goodness”, you’d then exclaim, “how easy is this new cooker compared to the old coal clunker! This lobster thermidor is cooked to a tee in half the time and practically serves itself!” And so forth.

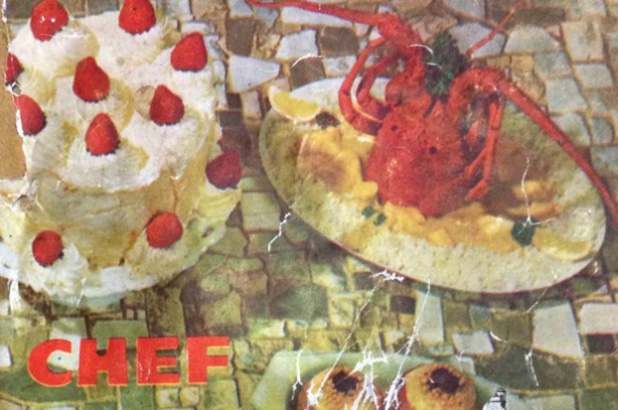

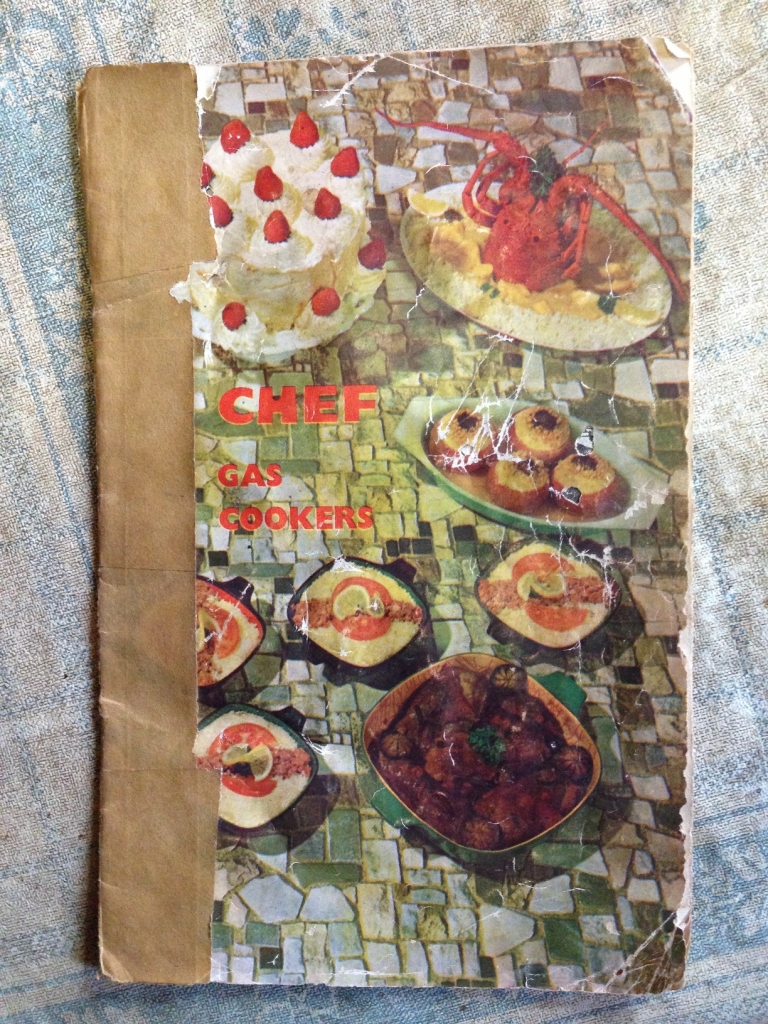

This Easter recipe is taken, not from a cookbook in its own right, but from a recipe booklet that accompanied a new ‘Chef’ brand upright gas 2-in-1 cooker that still sits in the kitchen at Rouse Hill, not far from the original coal-fired range. It was fueled by tall gas cylinders located outside the adjacent wall. The booklet, last used by Peggy and Gerald Terry, still sits on the kitchen table and shows the repairs needed after many years of use. Despite its small size the recipes (including ‘whiting caprice’, ‘sweet and sour fish’, ‘prawn croustades’, ‘salmon ramekins’, ‘chicken marengo’ and the more prosaic ‘browned pork chops’) must have been favourites. I particularly like the encouragingly optimistic cover – with a twist of the thermostat, it seems to say, you can cook anything from a casserole and stuffed tomatoes to a pavlova or a curried lobster!

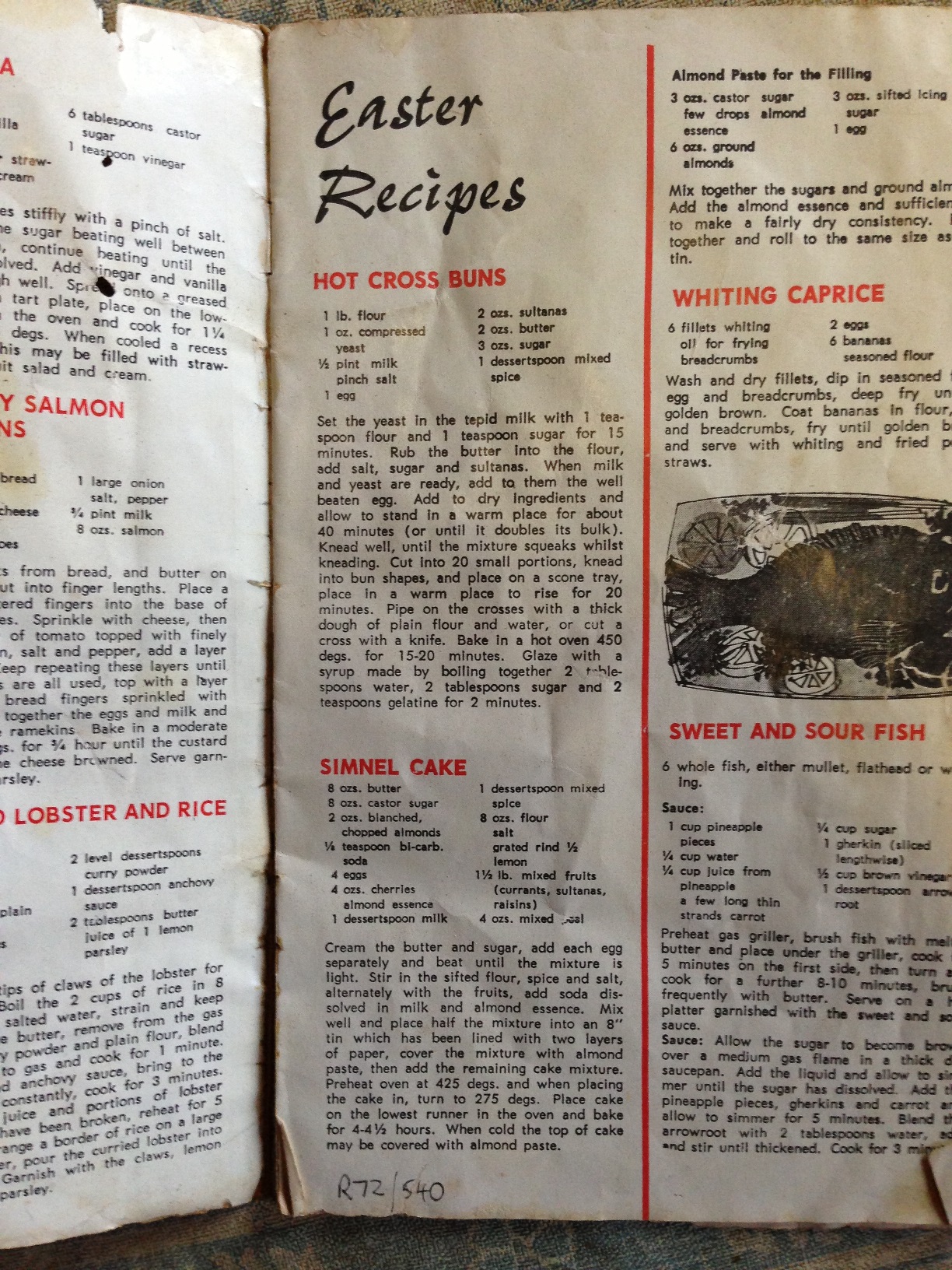

Its interesting that in such a slim booklet there’s still a dedicated page for ‘Easter recipes’. This recipe is for a ‘Simnel cake’, quite an old ‘traditional’ (we’ll get back to that term) cake loaded with spices, dried fruits and citrus peel and supposedly eaten when fasting concluded at the end of Lent. Jacqui notes its similarity to a German Stollen cake. Depending on who or what book or website you read, its also associated with ‘mothering sunday’ or servant girls returning home with a present for their mothers. The name Simnel is also up for discussion, but derives from the term used in the medieval and Tudor periods for fine white flour, the highest grade of flour, and was a term also applied to bread made from it.

What’s in a name?

The deathly titled An historical and chronological deduction of the origin of commerce (Snore and Yawn publishers, London, 1801), recounting court documents from 1266 in the reign of Henry III (As Anna Russell would say: “I’m not making this up you know!”) explains: “Wastel was of the fine sort of flour, yet simnel seems to have been finer than wastel, from which name of simnel the cakes still made in some counties took their name”. Samuel Johnson defined a simnel cake as being “a kind of sweet bread or cake” (Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, 1st edition 1755). Several 18th century mentions of Simnel Cake that I’ve read actually describe it as being ‘hard’, not exactly biscuit-like but in one example as being baked into a cup-shape and used to scoop up foodstuffs. Later nonsensical Victorian writers tried to ascribe the cake to a brother and sister duo, Simon (or Simeon) and Nell, who combined their names to create the title of a cake they baked. Its a story that is repeated again and again.

In a ‘trawl through Trove’ it’s interesting that Australian newspaper mentions and recipes for simnel cakes suddenly start in the 1880s, and their connection with the English town of Bury is noted – ‘Simon and Nell’ make their appearance a few years later. The cake’s connection with Bury was also recorded by – of all people – the great circus showman Phineas Theodore Barnum:

[This] cake was what is called in Bury, England, where name, cake and custom originated, a ” Simnel cake,” and an interesting history pertains to it.

There is an anniversary in Bury, and I believe only in that place in England, called “Simnel Sunday.” Like many old observances, its origin is lost in antiquity; but on the fourth Sunday in Lent, which is Simnel Sunday, everybody in Bury eats Simnel cake. It is a high day for the inhabitants, and the streets are thronged with people. During the preceding week, the shop windows of the confectioners exhibit a plethora of large, flat cakes, of a peculiar pattern and of toothsome [Im guessing he means ‘chewy’] composition. Every confectioner aims to outdo his rivals in the bigness of the one show-cake which nearly fills his window, and in the moulding and ornamental accessories. A local description, giving the requisite characteristics, says: ” The great Simnel must be rich, must be big, and must be novel in ornamentation.” Such is the Simnel cake, the specialty of Simnel Sunday, in the town of Bury, in Old England.

Despite the ambiguities of the internet and the inventiveness of the Victorians, the claims made for Simnel cake raise a simple question: exactly how long does something have to be done, such as a cake being baked, before it becomes ‘tradition’? A year? A decade? A century? “Yea back unto the Middle Ages?” I know that I can’t bide the thought of eating hot cross buns at any other time of the year than actually AT Easter. It’s just wrong to eat them in February despite what the supermarkets think. Its like only having the wisteria flower in spring or heading out for dumplings at Chinese New Year.

Simnel Cake a la the Terrys’ Chef cooker

8oz sugar

8oz castor sugar

2 oz blanched, chopped almonds

1/3 teaspoon bicarb of soda

4 eggs

4 oz cherries

almond essence

1 dessertspoon milk

1 dessertspoon mixed spice

8 oz flour

salt

grated rind of 1/2 lemon

1 1/2 lb mixed fruits (currants, sultanas, raisins)

4 oz mixed peelCream the butter and sugar, add each egg separately and beat until the mixture is light. Stir in the sifted flour, spice and salt, alternately with the fruits, add soda dissolved in milk and almond essence. Mix well and place half the mixture into an 8″ tin which has been lined with two layers of paper, cover the mixture with almond paste, then add the remaining cake mixture. Preheat oven at 425 deg[ree]s. and when placing the cake in, turn to 275 deg[ree]s. When cold the top of the cake may be covered with almond paste.

Almond paste for the filling:

3 ozs. castor sugar

few drops almond essence

6 ozs. ground almonds

3 ozs sifted icing sugar

1 eggMix together the sugars and ground almonds. Add the almond essence and sufficient egg to make a fairly dry consistency. Knead together and roll out to the same size as the cake tin.

Curator’s note: Many recipes from the late 19th century on suggest decorating the top with 11 small balls of the almond paste, representing the apostles less Judas. I’d also suggest this an invented tradition.

Read on MacDuff:

Trove? If you haven’t dug into Trove yet you’re in for a treat. Trove is the search engine for the National Library of Australia, accesses all the major public institutions as well, AND it incorporates the Australian Newspapers Online project.

Adam Andersen, An historical and chronological deduction of the origin of commerce, vol.1., (London, 1801) p 230

P T Barnum Struggles and Triumphs: Or, Forty Years’ Recollections of P. T. Barnum. New York, 1871. p514