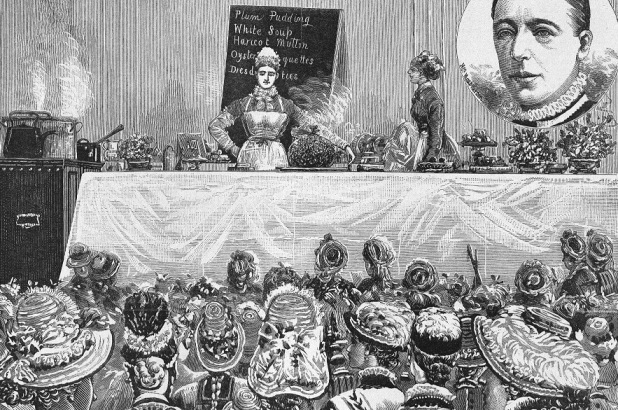

Judging by the fashionable dress of the women in Mrs Macpherson’s plum pudding class shown above, the traditional plum pudding was a standard requirement, if not the centrepiece, on all the best tables. But in the true spirit of Christmas, our archives tell us that the less fortunate were also tucking in to the classic plum pud!

Puddings hanging in the kitchen at Elizabeth Farm. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Role reversal

The Christmas celebration – mid-winter in the northern hemisphere – is said to hark back to the Roman festival Saturnalia, held in mid-to-late December. Feasting was an important part of the celebrations, but with a curious twist. For one of the feasts, masters switched roles with their slaves, allowing them to wear fine robes and be served at table by the master and his family – no doubt being extremely careful not to let this one day go to their heads! In Britain, by the turn of the 18th century the characteristics of ’12th night’ was slowly being transferred to Christmas day itself, and it gradually became a celebratory day rather one solely of religious observance. Whether for the under-privileged or for children, benevolence has been a Christmas virtue ever since. When you then added Prince Albert’s prodigious influence and the introduction of Germanic customs (especially gifts for children and Christmas trees), iced with a good layer of Charles Dickens, the contemporary concept of Christmas was firmly set.

The Hyde Park convict barracks, 1819

![Road gang [outside Hyde Park barracks] Sydney N.S. Wales. Augustus Earle, 1830. National Library of Australia](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2020/11/618x427xAUGUSTUS-EARLE-NLA-1830-CONVICTS-HPB-LON09_CONSYD_003_1_0-1024x709.jpg.pagespeed.ic.NPLph51ppK.jpg)

Road gang [outside Hyde Park barracks] Sydney N.S. Wales. Augustus Earle, 1830. National Library of Australia

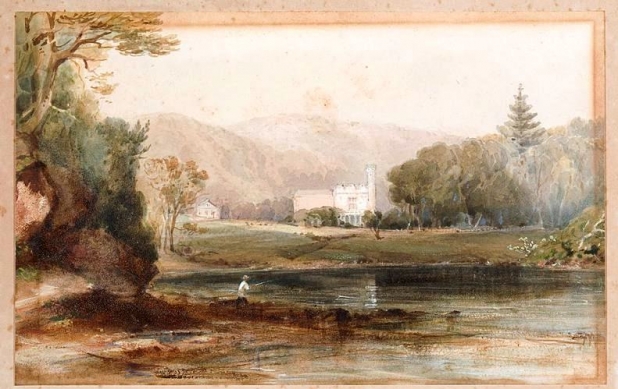

Vaucluse House, 1844

Vaucluse House from Vaucluse Bay, by Conrad Martens, 1841. © Sydney Living Museums

Household expenditure accounts from Vaucluse house from December 1844 show that the Wentworth’s bought in excess of seventy pounds (approximately 30 kg) dried fruit, peel and spices in the lead up to Christmas, with more purchased in January 1845. Mince pies were also bought in, so we can assume that there was a fair bit of Christmas pudding or cake being made (fruit cake was generally served on Twelfth Night – January 6). Albeit a large family, with eight children at this point in time, this volume of ingredients suggests that the Wentworths were catering for more than the family alone. The estate at Vaucluse accommodated a large number of staff, including domestic servants, stablemen, gardeners and labourers. It seems fair to assume that some of them may have been the recipients of all that fruit in the form of Christmas pudding.

Lake Innes 1850

Annabelle Innes (later Boswell) circa 1840. Photographer unknown. National Museum of Australia.

Annabella Boswell’s (nee Innes) wrote of her Christmas in 1850, later published in her memoir, Further recollections of my early days in Australia. It shows that the family catered Christmas lunch for their workers, with roast beef and plum pudding.

St Clair, December 1850 – My dear Margaret, since my last letter … was posted we have had a very merry Christmas, and I hope there is a happy New Year in store of us. On Monday 23rd, we were all up early… I made some shortbread and got ready the plums for the mince pies, and all the other ingredients for them and for the sponge cakes, and delivered them to James (the cook) who has made all the cakes this year, and does it very well.

On Christmas morning it was really very chilly. I was up before 5 o’clock – not because I had anything to do; I did not even witness the making of the plum pudding but I was chief maker of the “Old Mans Milk”, and saw Margaret up to her elbows in mixing a large plum pudding for the blacks, who had a grand dinner of roast beef and plum pudding laid out in a shed they had made with green boughs near the rabbit-house. There were sixteen of them altogether and they seemed to enjoy themselves very much.

Hyde Park barracks Asylum for destitute women, 1882

Dinner bowl (reconstructed) used in the Hyde Park Asylum for aged and destitute women, 1862-1886, excavated from beneath the floorboards at Hyde Park Barracks. UF9831c. Photo © Jamie North

In the dining hall the tables literally groaned beneath the weight of the good cheer provided. There was an abundance of good roast beef, that old staple dish at every English banquet, and an ample supply of other substantial viands, end several enormous plum puddings, which followed in due order, made the second course a toothsome dish for the guests, whose appetites had been somewhat sharpened by the fragrant odours which arose from the culinary department.

‘The Hyde Park Asylum’ Evening News, 27 December, 1882

No doubt the plum puddings served at this event were boiled in giant pudding cloths – or bed sheets perhaps!

Notes

Annabella Boswell (nee Innes), Further recollections of my early days in Australia Canberra, Mullini Press, 1992.