If you were looking at sideboards for your 1830s colonial house the biggest issues you faced, apart from style and cost, was the sheer size of the thing! Perhaps a chiffonier was the answer.

A tight squeeze

Chiffoniers are useful objects for families who cannot afford to go to the expense of pier or consol tables. …‘[They] may be used as a sort of morning side-board for containing any light species of refreshment.

John Claudius Loudon.

Today many houses, and certainly many apartments, have done away with the sideboard altogether as space – as much as changing dining habits – increasingly becomes an issue. This is a shame because sideboards really are useful places to store dinnerware (and in my house the table linen, a huge collection of dining paraphernalia and even a few bottles of the good wine). Back in the 1830s writers including John Claudius Loudon discussed the practical issue of space in small houses and cottages, and the use of the ‘chiffonier’ as an alternative to their more cumbersome relatives. Alternatively spelt ‘chefonier’ or ‘chefonier’, the chiffonier (from the French ‘chiffonierre’ = ‘rag gatherer’, suggesting a place of storage of small bits and pieces) was a popular choice for drawing rooms, parlours and sitting rooms where they functioned as a combination of bookcase, cupboard, table surface and open shelving for the display of ornaments or books. They’re really those rooms’ equivalent of the dining room’s sideboard.

They were a Regency innovation (the term does not appear for instance in Thomas Sheraton’s The cabinet dictionary of 1803) and could of course be grand or simple, in materials ranging from rosewood, mahogany and cedar, solid or veneer, to humbler timbers, and with fittings from gilt to brass. Some examples were fitted with mirrored panels and decorative marble tops could also be used. While some examples are quite tall, with a single or series of shelves, all share the basic combination of cupboard and shelving. This 3-shelfed example is on display at Vaucluse House:

Chiffonier at Vaucluse House, c1830-35. Caroline Simpson Collection, Sydney Living Museums. Photo © Sydney Living Museums

The larger version of the chiffonier is what what Loudon terms a ‘consol table’ (the Victorians were seriously obsessive about classifications, and furniture was no exception; the catch is that the same object often carries several names given by different writers – or even the same writer over time), and here the relationship to the pedestal sideboard can be clearly seen; Loudon’s consol table replaced a pedestal sideboard’s solid doors with glass panels and/or cloth curtaining, adds a display shelf supported on curving supports resembling a classical ‘console’ leg above the top (look at the curving supports in the Vaucluse example above to get the idea), and a long shelf at ground level linking the two ‘piers’. In this larger, broader example at Elizabeth Bay House (complete with lamps, books and nick-knacks) you can clearly see the design relationship:

Fully decorated chiffonier in the drawing room at Elizabeth Bay House. Courtesy Country Threads Magazine © Express Publications Pty Limited

In a nice spatial relationship, facing this through the enfilade doors that link drawing room, vestibule and dining room is that rooms pedestal sideboard, seen in my last post. In many houses where one room doubled as a dining room and parlour a chiffonier was an easy fit. You can often spot a chiffonier that was specially designed for a smaller room by its main drawer, which might be divided into baize-lined compartments for cutlery.

In 1883 Richard Twopeny wrote (rather sarcastically, and obviously for a British audience) of the furnishings of colonial homes. In the dining room the sideboard holds pride of place:

We will now go into the dining-room, which is probably the best furnished room in the house. It is not easy to make a dining-room look out of joint provided you are not particular about the cost, though there is a very wide margin between the decent and the handsome. The upholstery is much the same as in an ordinary upper middle-class house in England–sofa, sideboard, chiffonier, two easy and eight or ten upright chairs in cedar frames and covered with leather, marble mantelpiece and clock, Louis XVI. glass, and a carpet which is at any rate better than the drawing-room one. [1]

(I like the addition of a sofa or couch – which gave you somewhere to lie back between courses, especially if the table was being reset for dessert, or have a nap afterwards.)

In moderate houses the same pattern is followed, but the sideboard has been done away with altogether, replaced by a chiffonier and a side table:

The real living-room of the house is the dining-room, which is therefore the best furnished, and on a tapestry carpet are a leather couch, six balloon-back carved chairs, two easy-chairs, a chiffonier, a side-table, and a cheap chimney-glass. [1]

Variations on a theme

As sideboards evolved the next development was for the centre section, between the pedestals, to give up its sarcophagus (I know, sad face!) and be enclosed. This is what you see in this mid-century example from Throsby Park (near Moss Vale, South West of Sydney). The pedestal form is still echoed in the reverse breakfront:

Australian cedar sideboard, in the form of a pedestal sideboard with an enclosed centre, c1855. Throsby Park Collection, Sydney Living Museums. Photo © Rob Little / RLDI

And now, in large houses anyway, the sideboard really began to grow! The most common addition was a considerable, even vast mirror, made possible by improving glass technology.These often had a curved top, as in this example once seen in the dining room at Vaucluse House:

Dining room at Vaucluse House, Thomas J Lawlor, [1935?]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums Nielsen Vaucluse Park Trust photograph album no.4

If you remember the Wentworths’ Gothic Druce & Co. sideboard from my last post however you may be asking what on earth these beached ocean liners are doing in that room. The answer is that for many years Vaucluse House operated as a museum of ‘Australian historic objects‘, and all sorts of material ended up there on display. The dining room was occupied by not one but TWO of these behemoths as a result (accompanied by prominent donation cards), even blocking the window. What is marvelous though is that you can see the tiled floor clearly.

Styles varied widely, especially with the later 19th century Arts & Crafts and Aesthetic styles where asymmetry was common – about as far from the pedestal sideboard as you could get. The ‘dresser’ with its tiered shelving was also a major influence, especially amongst those designers who looked to the hand-made medieval for inspiration. By the late Victorian and Edwardian the large over-mantle with shelves for displaying porcelains (or bottles) was common:

The dining room at Bangoola Mosman, photographer unknown, 1912. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

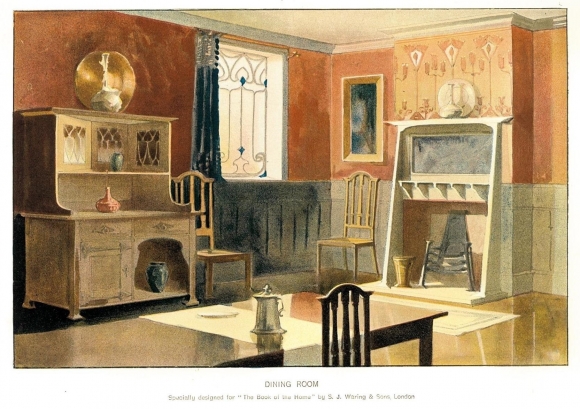

In stark contrast this design from the same period has restrained elements of the Art Nouveau, and shows a concerted move away from the heavy, imposing (and typically mass-manufactured) sideboards of the later 19th century:

Dining Room in H C Davidson, Ed., The book of the home – a practical guide to home management, The Gresham Publishing Co., London, Vol.1. 1906. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

This ca.1900 dresser/sideboard is from Meroogal. At first glance it seems very symmetrical – but look more closely at the drawers:

White oak sideboard at Meroogal. Photo John Storey © Sydney Living Museums

Alas with changing dining customs, and the much debated demise of the formal dining room, the sideboard has shrunk, become multi-purpose or simply became defunct in many houses. Perhaps more than other furniture the sideboard epitomises the heavy, pompous world of the Victorian era form which we’ve moved so far. Taste has also moved far away from particular timbers and styles – you only need to visit an auction house to see the procession of enormous mahogany and oak sideboards from downsized houses and deceased estates. With a TV dinner the coffee table took on the role of serving table and sideboard in one. At iconic Rose Seidler House the location of the table next to the kitchen counter meant that surface absorbed the role of multiple furniture items.

To close, here’s the Chionoiserie-themed dining room created by famous Australian interior designer Leslie Walford at his own apartment. It includes a really delightful small ca1825 Regency sideboard. The room was photographed in 2012 as part of an ongoing documentation project run by the Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection.

Dining room in designer Leslie Walford’s penthouse apartment, Double Bay. Photo © Brenton McGeachie for Sydney Living Museums

Second helpings

[1] Richard Twopeny, Town life in Australia. London, Elliott Stock, 1883.

The quotes on chiffoniers by John Claudius Loudon are from his Encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture entry no.2113 and fig. 1942. London, 1833.

And the Chevy Chase sideboard? That sideboard is named for its intricate carving which tells the (romantic, but totally incorrect) story of a battle of honour over hunting rights between Lord Percy (Hotspur) of Northumberland and Lord Douglas, Warden of the Marches. The battle takes place in the Cheviot Hills, the ‘Chevy Chase’. Wikipedia has an entry on it. Click here for a story about its conservation post-Katrina.