Publishing recipes in poetry seems to have been a nineteenth-century whimsy. Making reference to Eve’s proverbial ‘forbidden’ fruit, the apple, ‘Mother Eve’s Pudding’ was very popular in the early 19th century – with various renditions popping up in all manner of places, including the manuscript book of recipes which Mrs Thomas Mitchell (nee Blunt) brought to the colony in 1827.

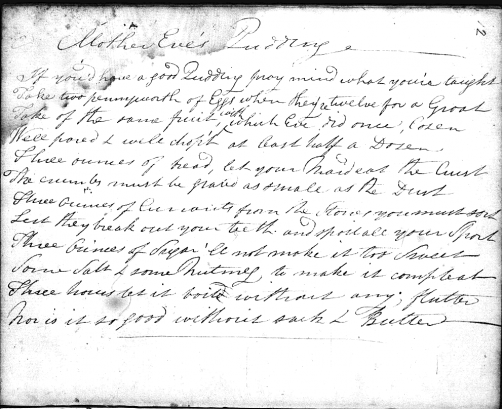

Mother Eve’s pudding, recorded in Mrs Thomas Mitchell’s book of recipes. 1827. State Library of New South Wales Call Number C 83.

A poet in the kitchen

According to a short biography from the Tonbridge Historical Society (Tonbridge, UK, where Eliza lived in the 1840s) Eliza sent the poem to her sister one Christmas. Its origins lie in a more straightforward recipe for ‘Eve’s pudding’ first published by Mary Eaton in The cook and housekeeper’s complete and universal dictionary in 1823 (p 121), a variation on the many fruit puddings we would now associate with Christmas pudding.

If you want a good pudding, to teach you I’m willing;

Take two pennyworth of eggs, when twelve for a shilling,

And of the same fruit, that Eve once had chosen,

Well pared and well chopped, at least half a dozen;

Six ounces of bread – let your maid eat the crust,

The crumbs must be grated as small as the dust;

Six ounces of currants from the stones you must sort,

Lest they break out your teeth, and spoil all your sport;

Six ounces of sugar won’t make it too sweet,

Some salt and some nutmeg will make it complete;

Three hours let it boil, without hurry or flutter,

And then serve it up, without sugar or butter.

Source: Tonbridge Historical Society

A groat?

A variation appears in Edward Abbott’s English and Australian Cookery book (for the many and the upper ten thousand), the first cookbook published by an Australian, in 1864.

If you would have a good pudding, observe what you’re taught :

Take two pennyworth of eggs, when twelve for a groat

And of the same fruit, that Eve once had chosen,

Well pared and well chopped, at least half a dozen;

Six ounces of bread – let your maid eat the crust,

The crumbs must be grated as small as the dust;

Six ounces of currants from the stones you must sort,

Lest they break out your teeth, and spoil all your sport;

Six ounces of sugar won’t make it too sweet,

Some salt and some nutmeg will make it complete;

Three hours let it boil, without hurry or flutter,

And then serve it up, without sugar or butter.A British groat. Image courtesy Coin Trust UK.

Who’s counting?

Herein lies a consistency problem in the wording, and possibly in the consistency pudding itself: how many eggs when a dozen a groat? According to a quick internet search, a groat is 4 pence, so Abbott’s recipe will be made with half a dozen eggs. Eliza’s, on the other hand, with ‘two pennyworth of eggs, when twelve for a shilling’ would have only two eggs…

While hardly poetic, the original 1823 recipe is more concise – three-quarters of a pound (340 g) each of breadcrumbs, suet, pared apples and currants, four eggs, and the juice and rind of a lemon. I’m yet to test any of the three versions – but definitely on the ‘to do’ list.

References:

Eaton, Mary. The cook and housekeeper’s complete and universal dictionary; including a system of modern cookery, in all its various branches, adapted to the use of private families: also a variety of original and valuable information, relative to baking, brewing, carving … and every other subject connected with domestic economy. England, 1823

Acton, Eliza. Modern Cookery for Private Families. Southover Press, London. 2002 (first published in 1855) Reprint of the extended edition of 1855 as edited by Eliza Acton.

Abbott, Edward. The English and Australian cookery book for the many and the upper ten thousand. 1864. Available in facsimile through TasFoodBooks Australia.