No city is without its skyscrapers, and Sydney is no exception. All eyes seem to be on the current developments at Barangaroo on the western foreshores below Millers Point, which itself was named after the sailed flour mill run by John Leighton – known as ‘Jack the Miller’. This, and the many other mills that sprang up on Sydney’s natural ridges and headlands were the town’s tallest structures for decades, and key landmarks for locals and visitors alike, including artists, writers and poets, including William Charles Wentworth, who would later reside at Vaucluse House:

The lofty windmills, that with outspread sails

thick line the hills, and court the rising gale…

William Charles Wentworth, Australasia 1823 [1]

![Joseph Lycett [Sydney from the north] (detail) 1825. State Library of NSW: DG SV1 / 13](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2016/02/618x181xLYCETT-NORTH-VIEW-WINDMILLS-detail-1825-LON11_GVT_056-1024x300.jpg.pagespeed.ic.yf8edkWs8m.jpg)

Joseph Lycett [Sydney from the north] (detail) 1825. State Library of NSW: DG SV1 / 13. The ‘government mill’ is located on the left behind the grand government stables (now the Conservatorium of Music); two others stand on Observatory Hill and Millers Point and another can be seen in the distance, far right.

Sydney’s first skyscrapers

The view of Sydney by Joseph Lycett (above) and a three part panoramic view by Major James Taylor (below) give an idea of the number of mills in use in Sydney town at the time. They depict both stone ‘tower’ mills and awkward looking wooden ‘post’ mills (shown in closer detail later in this article); some government operated and others by enterprising individuals such as ‘Jack the miller’.

Panoramic views of Port Jackson, ca. 1821 / drawn by Major James Taylor, engraved by R. Havell & Sons. © State Library of New South Wales call numbers V1 / ca. 1821 / 4, 5, 6.

A hard grind

Once the colony started producing its own wheat (which is another story in itself – wracked with crop failures but we’ll keep that for another time), the grain had to be processed into flour using hand mills, or ‘querns’. Forty iron hand-mills were sent out with the fleet but were of poor quality and soon rendered useless. A convict named James Wilkinson revolutionised wheat processing in the 1790s, by devising a ‘man-mill’:

His machine was a walking mill, the principal wheel of which was fifteen feet in diameter, and was worked by two men; while this wheel was performing one revolution, the mill-stones performed twenty… The heavy part of the work, cutting and bringing in the timber, and afterwards preparing it, was performed by his fellow-prisoners, who gave him their labour voluntarily. [2]

Some forty years later another man-powered mill was in use – the treadmill powered by convicts which we’ve spoken about in the past.

A long wait

‘4 pair Millstones, with the necessary apparatus and gear for two windmills’ are included in a 1792 invoice of ‘Articles to be sent to New South Wales, in consequence of Governor Phillip’s representations’, however it appears this never eventuated, with the shipment arriving with Governor Hunter in September 1795. [2] Almost a year later though, the town was still without these and other vital assets such as new barracks, strong prisons, schools, churches and better hospitals:

List of Public Buildings much wanted, August, 1796:

At Sydney: A windmill. None yet erected.At Parramatta: A windmill or two. Two will be necessary here, because our largest farms are in this district. [3]

It seems there simply weren’t enough skilled tradesmen to build the infrastructure required and Hunter feared that ‘much of the wheat purchased at the proper seasons would be lost by vermin. I am therefore anxious to have it ground into flour as early as possible.’ [4]

Panoramic views of Port Jackson (detail), ca. 1821 / drawn by Major James Taylor, engraved by R. Havell & Sons. State Library of New South Wales. Call number V1/ca.1821/5. This image shows the military mill, near where Wyndyard station is now situated.

Finally, that November, Hunter was able to report

We are also erecting upon the high ground over Sydney a strong substantial and well-built windmill with a stone tower, which will last for two hundred years , and we are preparing materials for another such at Parramatta. These two mills, when finish’d, will occasion a saving considerable by issuing flour instead of grain. [5]

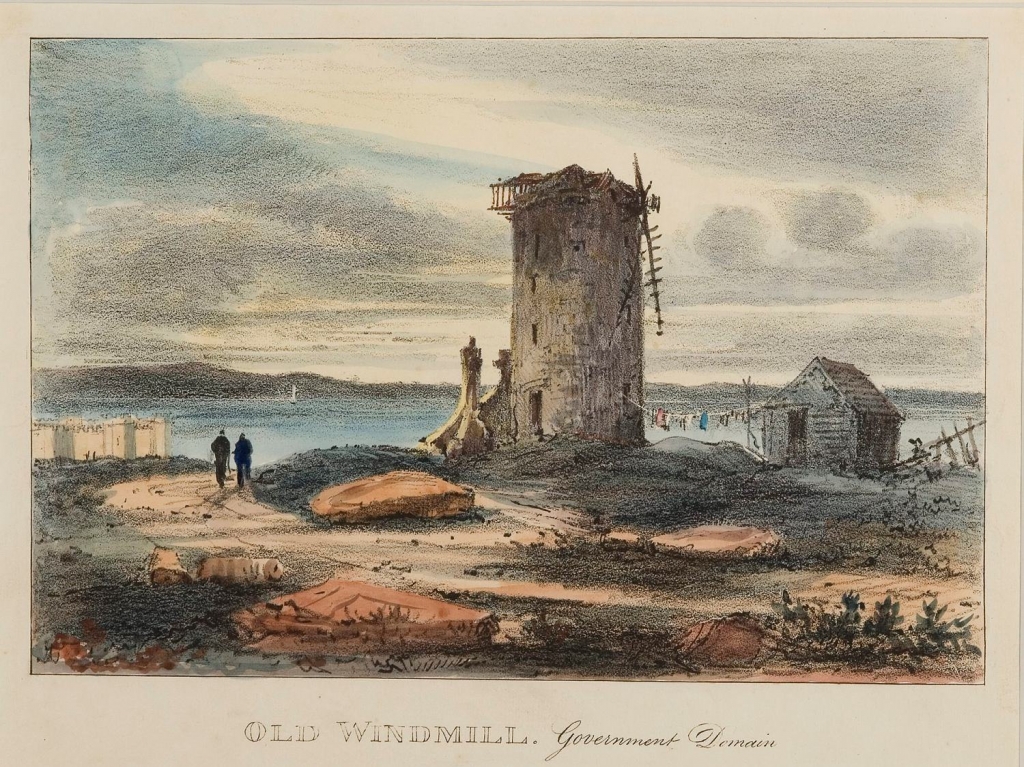

Hunter’s claim was somewhat ambitious, as the mills fell into disrepair as the 19th-century progressed as the example below, of the ‘government’ windmill in the Domain shows:

Old windmill, Government Domain (November, 1836) by Russell, Robert, (1808-1900). © Caroline Simpson Collection, Sydney Living Museums

All in vane

The Sydney mill was built on Fort Phillip, where the Observatory now stands, near The Rocks. It was a short-lived venture: people were obliged to pay almost half their grain to have the other half ground. In an extraordinary act of vandalism (or revolt, brought about, perhaps, by frustration over prices), some ‘worthless villains’ stole some of the sails from the windmill’s vanes and the mill ‘was consequently stop’d’, leaving Sydney without grinding facilities until repairs could be made.[6]

Old [post style] mill, Gordon St, Paddington, Sydney, 1862 / George Roberts. © State Library of New South Wales call number V1/Pub/GovH/9a a928314r

Lost Sydney

Watermills were also used along the Parramatta River and other waterways, but as technology advance, more efficient steam-powered mills, such as the one advertised by the colourful French baker, Francois Girard, at cockle bay in 1834.[7] According to F. J Croft, in a newspaper article published in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1938, the last of the Sydney windmills ‘was levelled to the ground on October 1, 1878. It was situated on Old South Head, near the Waverley tollbar’.[8] Remnants of some of the old stone mills still survive, their sandstone blocks recycled and obscured in stairways and walls about town. [9]

John Skinner Prout, ‘Millers Point Sydney From The Flagstaff Hill’ 1842. State Library of NSW, DL Pe 257

By 1842, when John Skinner Prout drew this view, the skyline of Millers Point was changed forever. One of Leighton’s windmills is still standing but is now surrounded by houses, and its distinctive profile competes with an imposing new row of terraces to its right and the stepped elevation of Albion House to its west (left). Note also the boldly labelled Lord Nelson hotel, which still stands today, on the far right – but we digress…

So what of ‘Jack the Miller’ himself? Despite his entrepreneurial success his was not to be a happy tale. In May 1824 there was apparently domestic strife in the household, and Leighton placed an advertisement warning the public that he would not be accountable for his wife Anne or son David’s debts. Later that year he was brought to court accused of adulterating flour [10] produced in his mill, and 2 years later catastrophe struck when he was found dead, having fallen in a drunken state from one of his mills. His nickname survives to this day.

Notes

[1] William Charles Wentworth. Australasia. 1823.

[2] Undersecretary King to Phillip. January 10, 1792. HRA vol 1. p 333.

[3] Hunter to Portland August 20, 1796. HRA vol 1. p 595.

[4] Hunter to Portland September 20, 1796. HRA vol 1. p 665.

[5] Hunter to Portland November 12, 1796. HRA vol 1. p 675.

[8] Sydney Morning Herald Saturday 2 April 1938

[9] For example the Beare’s stairs in Caldwell Street, Darlinghurst (see http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/darlinghurst)

[10] The Sydney Gazette, 23rd December 1824