The once ubiquitous fruit cake, which was available by the slice at the counters of many a tearoom, cafe or corner shop – may become a Christmas-time only indulgence. Regular readers of The Cook & the Curator will know that plum puddings were not limited to the festive season, but enjoyed throughout the winter months in colonial times. Today we only have them at Christmas and ‘Yule-fest’ occasions. With the prevalence of decadent macarons, fancy cup cakes and over-sized muffins these days, it seems that the traditional fruit cake is destined for the same fate.

‘Rich’ fruit cakes

While the ‘boiled’ fruit cake, which became a ‘classic’ in early 20th-century Australia as everyday fare, ‘rich’ fruit cakes – made with generous proportions of exotic fruits and fragrant spices were made for special occasions. Recipes in our collections show that fruit cakes were made for Christmas but also weddings and birthdays.

‘Twelfth Night’ from ‘The book of Christmas’ by Thomas Kibble Hervey, illustrated by Robert Seymour. William Spooner, 1836 [preceding p. 333]

Twelfth Cake

Despite Christmas cakes being advertised in colonial newspapers, it is the iconic plum pudding that appears central in family letters, recipe collections, literature (Dickens A Christmas Carol comes immediately to mind), with little mention of cake. Rather, it was tradition to serve ‘rich’ fruit cake on ‘Twelfth Night’ – January 6, which celebrated the religious festival of the Epiphany, an occasion now largely forgotten on the Australian popular festive calendar .

Advertisement for Christmas and 12th night Cakes. The Australian 8th January, 1842. Source Trove Newspapers Online

Dolly’s ‘Xmas cake’ recipe 1912

The recipe for Christmas Cake in Dolly Youngein’s Fort Street School homework book from 1912 is a significant contrast to the ‘plain’ style of cookery taught in schools at this time (see metricised recipe below). It contains about 1.5 kg of fruit, plus preserved ginger and nuts, almost 1/2 kilo each of butter and sugar and 8 eggs so was indeed, very rich. That it features brandy is somewhat surprising for a recipe being taught to students as young as Dolly, who was 12 at the time. (And an issue that would later come to dog a Melbourne school cookery educator, Flora Pell, but that’s a whole other story in itself). It’s a delicious cake, easy to make, and it keeps well.

1 lb butter

1 lb brown sugar

1 lb 4 oz plain flour

1 lb currants

1 lb sultanas

8 eggs

1/2 lb citron peel

1/4 lb almonds

1/2 lb prunes

1/4 lb preserved ginger

1 wine glass brandy

1/2 teasp cinnamon

1 teasp [vanilla] essenceCream butter [and] sugar

Beat the eggs (add caramel to it if liked)*

Pour in the [butter/sugar] cream gradually

Put all ingredients in except flour, put it in last.

(* caramel was a commercial colouring agent)

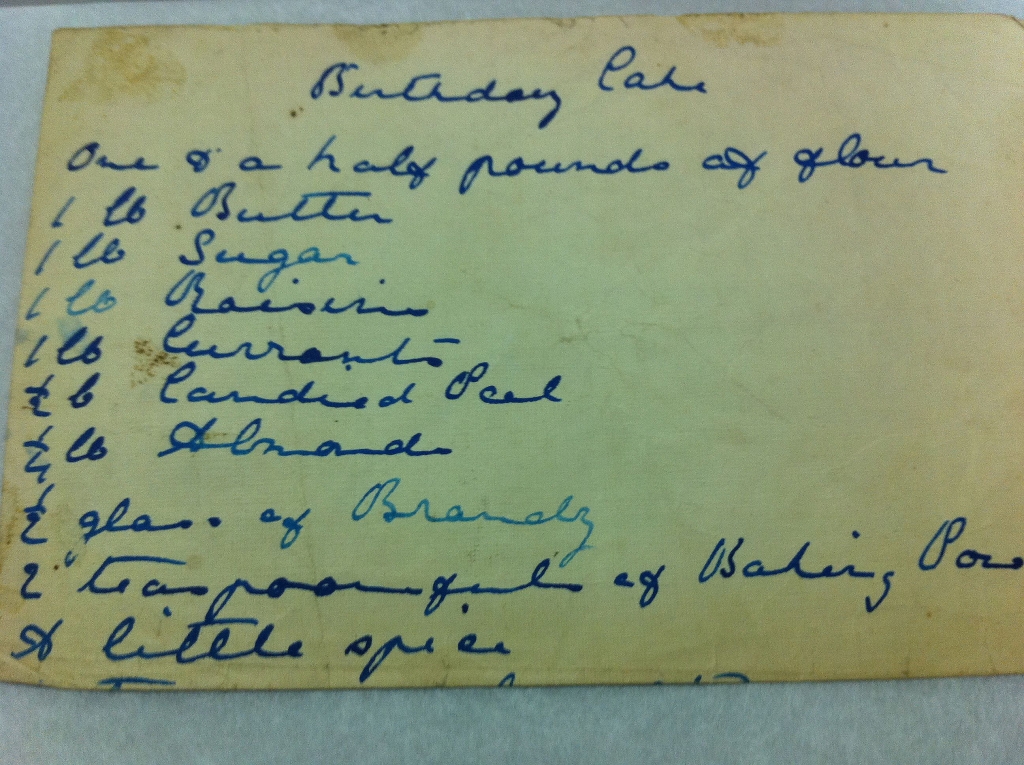

Birthday Cake, Rouse family style

Our archives show that fruit cake was highly regarded in the 19th century, taking pride of place at weddings and birthdays. ‘Rich’ fruit cakes as opposed to regular ones were made for these occasions, containing more ‘exotic’ fruits, spices and often, brandy or rum. A Birthday Cake recipe from Rouse Hill House and Farm, believed to date to the late 1800s or early 1900s is strikingly similar to Dolly’s Xmas Cake above, lacking only the prunes (it also asks for 8 eggs, and a teaspoon of salt).

Birthday cake manuscript recipe (top part). Rouse Hill House and Farm collection. © Sydney Living Museums

Bride of place

Tottie Thorburn from Meroogal, was renowned in the Shoalhaven district for the ‘very rich’, fragrant and ‘beautiful’ wedding cakes she made ‘for so many friends and relatives’. Tot’s niece Helen Macgregor recorded the recipe from Tot’s own handwritten copy in a ledger book of family favourites – the fully transcribed manuscript book can be accessed here, but ‘watch this space’ – we’ll talk more about that around Valentine’s Day.

A post script –

While researching wedding cakes for our Valentine’s Day story I came across one very helpful tip in an 1890’s edition of Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery, about fruit cake making:

‘[The cake] will improve with keeping – indeed, confectioners do not use their cakes until they have been made some months; and if a cake is cut into soon after it is made it will crumble.’

Sure enough the wedding cake I made from Tot’s recipe was eaten quickly after the photography was finished (we’re an ill-disciplined lot here in the office and succumb to temptation very easily!). It was indeed, difficult to cut, and very crumbly. I blamed my cooking skills, but perhaps if we’d left it for a few weeks it would have held together a bit better. This is a good lesson for Christmas cake making, and may be the reason why cakes were made earlier in the year and ‘fed’ with brandy or sherry, adding richness but also to assist with their keeping quality. Interestingly people talk about making Christmas puddings early too, however this is not supported in 19th century cookbooks.

Dolly’s ‘Xmas cake’ 1912

Ingredients

- 450g currants

- 450g sultanas

- 225g mixed peel

- 225g pitted prunes

- 110g blanched almonds

- 110g crystallised ginger

- 150ml brandy

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

- 450g butter, room temperature

- 450g brown sugar

- 8 eggs

- 575g plain flour, sifted

Note

This is one of the most elaborate recipes recorded by 12-year-old Dolly Youngein in her Plain Cookery course homework book from Fort Street Public School. It's fruit rich and delicious, at Christmas or any other time of year.

This recipe makes one very large cake, but I prefer to make it into two standard-sized cakes – one to cut and one to give as a gift.

Directions

| Position the oven rack one level below the centre of the oven and preheat the oven to 160°C (150°C fan forced). Lightly grease 2 x 20cm square or round cake tins and line base and sides with double layers of brown paper or baking paper. | |

| Mix the fruit, almonds and ginger together in a large bowl, stirring or mingling it with your hands to distribute the varieties evenly. Stir in the brandy, vanilla and cinnamon. In a separate large mixing bowl, cream the butter and sugar with electric beaters until light and pale. Beat in the eggs one at a time. Fold the fruit mixture into the butter mix, then add the flour, stirring lightly to incorporate it into the batter. | |

| Transfer the batter into the prepared tins. You may need to spread it to the edges and smooth the top. Bake for 2 hours, or until it is firm to the touch and a skewer comes out clean. If the top browns before it is cooked through, cover it with a double layer of baking paper. If the two tins are sitting closely side by side, swap them about for even cooking. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe