Kung Hei Fat Choy from all at the Cook and the Curator! Today marks the start of the 2013 Chinese lunar year – ‘the Year of the Snake’.

Of snakes and settlers

For early settlers the Australian wildlife was an eye opener – and no doubt for the Irish it was the snakes that took a lot of getting used to. At Vaucluse Sir Henry Brown Hayes, who hailed from Cork, apparently had Irish peat imported to lay as a ‘moat’ around his cottage. Irish soil, being blessed by St Patrick, would – he hoped – keep the snakes from invading his house. Along with kangaroos, wallabies and assorted birdlife, snakes were a crossover from the indigenous to the colonial diet in the very earliest years of the colony.

Lieutenant Ralph Clark wrote that ‘nothing goes a miss here Snakes and Lisards are become good eating but these I cannot yet to bring myself to Stomack’. His fellow officer, the chronicler Captain-lieutenant Watkin Tench (1759-1833), was more adventurous: ‘[I have] often eaten snakes, and always found them palatable and nutritive’. While the tried and tested indigenous method was to roast a snake in the coals of a fire, it seems Tench was eating them cooked more like eels, as he noted he found it ‘difficult to stew them to a tender state.’

But we digress…

To mark Chinese New Year we introduce our first guest blogger: our colleague Michael Lech, who is the HHT’s curator of Online Collections Content. Michael discusses a wonderful album of Chinese paintings from the Caroline Simpson Research Collection. While snakes don’t make an appearance, a whole section deals with the growing and production of tea, and of the porcelain from which it was drunk.

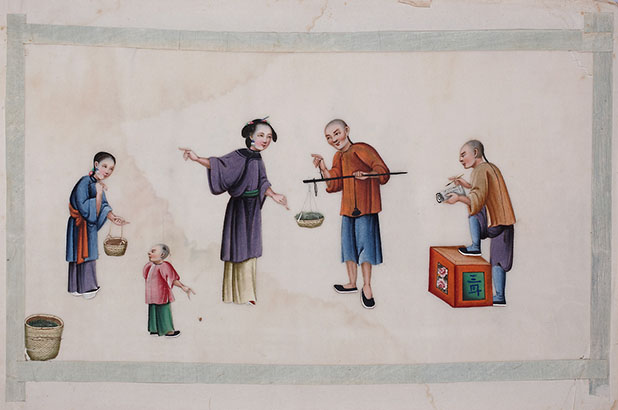

1. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

2. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

3. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

Chinese tea paintings

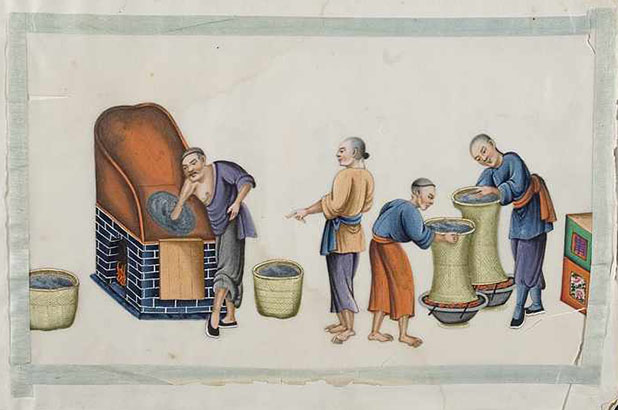

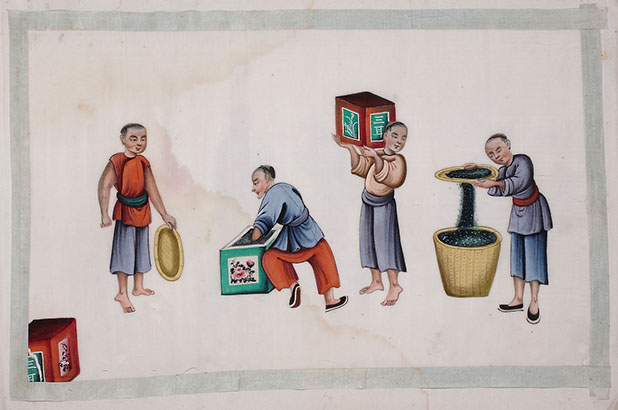

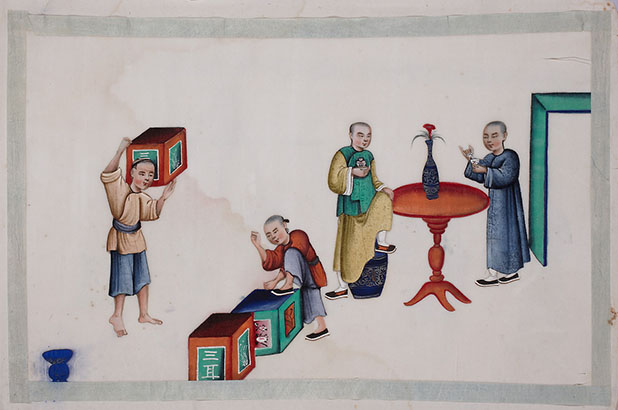

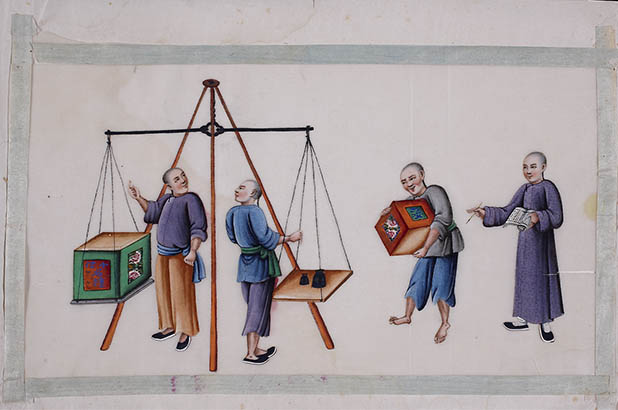

These beautifully vivid images depict stages in the Chinese production process for tea, from preparing the ground for planting to weighing tea chests for export. The images and ones like them were produced in their thousands throughout the 19th century mostly for the Western tourist trade.

Although they may resemble enamel paintings, they are actually watercolours on pith paper. Pith is not manufactured, but derived by cutting the inner spongy tissue of a small tree, Tetrapanax papyriferum, which is indigenous to southern China and Taiwan. Most pith paper watercolours, like these examples, are unsigned, though the majority are known to have been produced in Canton where numerous workshops existed. Individual images were often pasted into 19th and early 20th century Australian scrap albums, but it was common to buy the images in sets of 11 or 12, bound into albums with silk brocade covers. The pith paper was supplied held in place on a backing sheet and usually surrounded by a silk or paper ribbon.

4. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

5. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

6. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

7. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

Although tea production was often depicted in these albums, a variety of other subjects are common, mostly depicting colourful Chinese customs or practices that were seemingly exotic to Western eyes, including: street trades; flowers, animals & insects; production of other Chinese export commodities like rice, silk and porcelain; theatre scenes; ports and landscapes; Mandarins and ladies in colourful costumes.

One Western visitor to Canton in 1844 described these watercolours on pith paper in this way:

“…nothing can exceed the splendor of the colours employed in representing the trades, occupations, life ceremonies, religions, etc, of the Chinese, which all appear in perfect truth in these productions. Everything enacted in life, from the highest pageants of religious ceremonial to the lowest scenes of shamless debauchery, are given in the paintings. Not only the proper colours, but the exact attitudes of the figures are worthy of admiration.”

(quoted in Carl L Crossman, The decorative arts of the China trade, Antique Collectors’ Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 1991, pp.200-201)

8. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

9. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

10. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

11. Album of Chinese paintings showing stages of tea production, watercolour on pith paper, 19th century. Caroline Simpson Collection, Historic Houses Trust: L2007/174-2

Further reading

Rickard & Broadbent, India China Australia: Trade and society 1788 – 1850. Sydney, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 2003.

The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-1792. July 1788. p265

Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson. 1789.