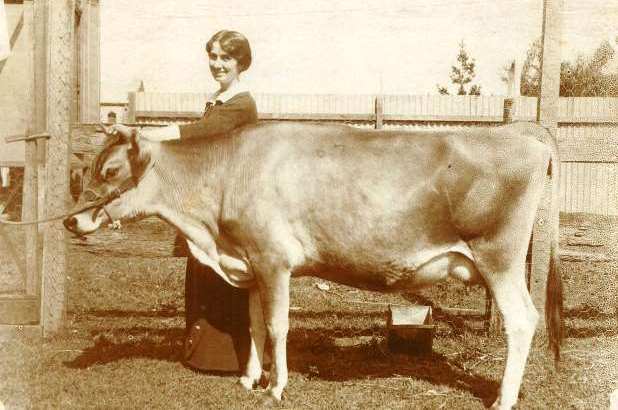

“Where are you going to, my pretty maid? I’m going a milking sir, she said”

This verse is written on the back of the above image of Margaret Ross Steel (nee Macgregor) by its photographer, James Barnet Steel, whom this pretty maid married in 1912. Their daughter, June Wallace, was the last of the family descendants to reside at Meroogal. But what does milking have to do with bread…?

Home made soda bread (wholemeal). Photo © Jacqui Newling

A shared tradition

In fact this story is about soda bread, which is generally associated with Irish heritage, but others from the broader community took advantage of this non-leavened bread-making technique. The English Bread book for domestic use (Eliza Acton, 1857) includes an ‘Excellent dairy bread, made without yeast’, a method of bread-making which is ‘common in many remote parts both of England and Ireland, where it is almost impossible to procure a constant supply of yeast.’ The ensuing instructions are for what we know as soda bread.

Kennina (Tottie) Fanny McKenzie Thorburn, 1886. Grouzelle & Cie. Sydney Living Museums, June Wallace papers, Rec no 43029

Of dairies and diaries

Tottie Thorburn who lived at Meroogal from 1893 – 1945, kept diaries between 1888 and 1896, which contain several references to homemade soda bread. One entry from August 1890 suggests that soda bread was the norm in the Thorburn household during this time:

Saturday 16 August 1890

Did a lot of cooking, made yeast bread for the first time in 4 or 5 years Uncle says it is good better than the bakers…

At this stage Tottie was living with her grandparents in rural Cambewarra, not far from Nowra on New South Wales’ south coast, but she visited Meroogal frequently. Although trips to town were not uncommon, Tottie made her own bread, a practice she continued when she moved in with her widowed mother, Jessie and three sisters, Kate, Belle and Georgie at Meroogal, in 1893. Yeast would not have been difficult to procure, but clearly, soda bread suited Tottie’s family’s tastes.

Wednesday 11 April 1888

Up early & made puff paste the morning was too warm, therefore the paste was not as good as usual Made scones & soda bread for Belle Very quiet all day without Grandfather…Thursday 26 April 1888

Up first cooked cakes scones & soda bread for Belle. What comforts we have here in this house Meroogal, I wonder how we dare to murmur, when we have so much, just innumerable blessings …Tuesday 17 July 1888

Tired this morning cleaned out the stove made melon ginger baked a lot of scones & soda breadTuesday 20 May 1890

Made cakes scones soda bread, tarts & puddings Melon ginger & melon jam, afternoon read some of “The Last days of Pompei”, [sic] sewed awhile went to the office for a walk.Monday 14 July 1890

Bert bad with cold & sore throat. Florrie brought Aleck & him some cakes & soda bread which were duly appreciated. Stayed a good while & Aleck came part of the way home with us. Bert was not well enough to come out. We enjoyed a sit round the fire.Monday 30 December 1895

Another lovely cool day made some scones & soda bread

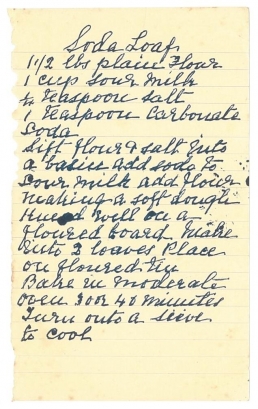

Soda Loaf recipe, thought to be in Tottie Thorburn’s hand; June Wallace papers, Caroline Simpson Library and Research collection. © Sydney Living Museums

It’s as simple as bread and butter[milk]

The key to soda bread is ‘soda’ – bicarbonate of soda and soured milk, or cultured buttermilk which was commonly available as a by-product of butter making. Cream was allowed to ‘ripen’ or mature for a day or two before being churned into butter, the buttermilk being the watery whey-like liquid that is expelled as the fats in the cream bind to make butter. ‘Real’ buttermilk clots and thickens naturally as it ages, but you can add acid (lemon juice or white vinegar) to fresh milk and use the resulting soured milk, or simpler still – purchase some commercial buttermilk, which has been cured. The soda reacts with the acidic culture in the buttermilk, helping the bread rise and producing a light texture. .

It was not uncommon for people to keep a house cow (such as the one shown above) and make their own butter, and before they became highly industrialised, local dairies and creameries were in reach of many householders, even in urban areas. Tottie mentions getting milk and cream from her good friends, the Binks, who were dairy farmers, and we can presume there was plenty of buttermilk to be had.

Incidentally…

buttermilk is the key ingredient in the ‘signature’ scones made by our local CWA Sydney branch – yes, the Country Women’s Association has a very active and vibrant city branch in the heart of the city! The ratio of ingredients is slightly different – using a a bit more butter – but essentially reads as a typical soda bread recipe, as does the method, the only difference being forming the dough into small pieces rather than a loaf.

CWA Sydney branch scone mix

2 & 1/2 cups self raising flour; 1 tablespoon icing sugar or 2 tsp sugar; 50 grams butter; good pinch of salt; 1 & 1/4 cups [store bought] buttermilk

Freshly baked soda bread © Jacqui Newling

Soda bread

Ingredients

- 300g wholemeal self-raising flour

- 150g white self-raising flour

- 1 heaped teaspoon bicarbonate of soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon dark brown sugar

- 25g butter, chopped into small pieces

- 500ml buttermilk ((store-bought cultured buttermilk))

- 50–100ml buttermilk, extra

Note

There are many soda bread recipes available – this is one I have had consistent success with, based on Tamsin Day-Lewis's 'Brown Soda Bread' from West of Ireland Summers (Orion Publishing Group, 1999).

Directions

| Preheat the oven to 230ºC. Grease a 20 cm cake tin or 23 cm loaf tin and line with baking paper, or for a free-form loaf, use a flat baking tray. Mix the flours, soda, salt and sugar together, and lightly rub in the butter until there are no detectable pieces. Make a well in the centre of the flour mixture and add 2 cups (500 ml) of the buttermilk, reserving the rest. Use a knife to mix from the centre of the well, slowly gathering the surrounding dry mixture into the buttermilk to make a soft, wet dough. If the dough is dry (which may depend on the flour itself and seasonal or ambient conditions), add extra buttermilk in small increments to make a tacky dough, and shape a loaf according to your preferred tin or tray – you may have to smooth over the surface if it looks rough. Transfer the dough into the lined tin, and if following Irish tradition, cut a 1 or 2cm deep criss-cross into the dough, which helps the centre cook through. Bake for 30–40 minutes, until it starts to brown on top and smell fragrant. Cover the top with baking paper and continue cooking for 15 minutes, until the loaf sounds hollow when tapped and a skewer inserted into the centre comes out clean. Rest for 5 minutes before turning out onto a wire rack to cool; wrap in a clean tea towel if you want a softer crust. Allow to cool before slicing and cool to room temperature before storing. The bread should last a few days in an airtight container, or can be sliced and then frozen, ready for use – it makes excellent toast. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe