Most First Fleet or early settlement histories concentrate on rations and the eventual lack thereof when talking about food in the early years of the colony. But as a gastronomer, and for the purposes of this blog, I am curious about what the colonists did with their rations? In other words, what did they actually eat?

First Fleet foodies

Fortunately, several diarists and record keepers appear to have had a strong interest in food – I like to think of them as our First Fleet foodies.

Sadly, the convict class is all but voiceless, as the surviving material is almost exclusively from officers or upper-ranking marines. Their journals don’t give menus or recipes per se, but they do reveal a lot about what was eaten and give an idea of contemporary tastes. Contrary to popular belief, they also show how readily the Europeans experimented with native ingredients as potential foods and used them to supplement the rations brought out from England.

Convict of New Holland by Juan Ravenet in Felipe Bauza 1793. State Library of NSW call # SAFEDGD 2

The settlers’ larder

The colony’s food resources can be divided into three categories:

1. Salt rations – based on long-standing English naval practices, every colonist was entitled to receive a set quantity of rations each week:

‘Standard’ ration, per week per man:

Salted pork 4 lbs or beef 7 lbs (250g or 450g respectively, per day)

Flour or bread 7 lbs (450g per day)

Pease (dried peas) 3 pints (1 cup per day)

Rice ½ lb (30 g per day)

Butter (ghee) 6 oz (25g per day)

Although it seems quite basic, when evaluated with a modern understanding of nutrition, the set rations provided more calories than currently recommended for a labouring man. Women received three-quarters and children half the standard issue. The rations allocation was often reduced and articles substituted depending on availability (a bit like futures trading). Marines and officers received a daily quota of rum which convicts were not privileged with. Rations were doled out once a week but, to the authorities’ dismay, many convicts ate, traded (usually for rum) or gambled their week’s allocation within days, and spent half the week hungry, or stealing someone else’s food.

2. Wild food – it was expected that fresh food would be procured from the natural environment – fish, seafood, game birds and animals, edible fruit and greens. The colonists experimented extensively with an array of flora and fauna, fish and feathered species, from sting-rays to witchety-type grubs and anything that could fly. They also made efforts to discover what foods Aboriginal peoples ate. While the two communities did not necessarily share the same tastes and ingredients (it appears the local Aboriginal people refused to eat sting-rays or sharks), the local peoples’ pantry was significantly impacted by the increase in population, the intrusion of a permanent settlement and all the activity it entailed. The impact on fish stocks was particularly significant for the Sydney Harbour clans, especially in the winter months.

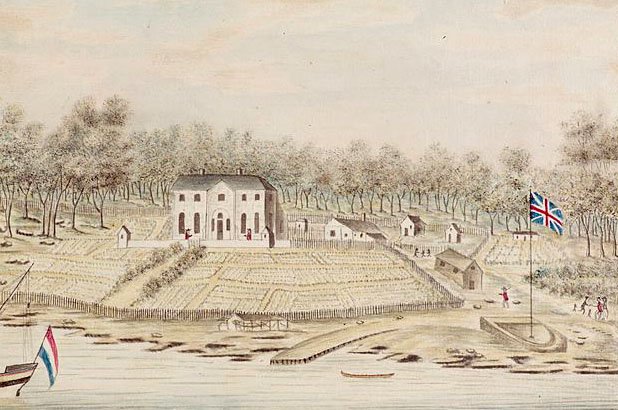

3. Farmed food – food gardens were integral to colonial life – a public garden was established in the area which is now Sydney’s Domain; convicts tended their own gardens; the hospital and the marines’ barracks had gardens and Garden Island (still used as a naval base) was reserved for the crews aboard the ships in harbour. Even the governor had his own garden, which was planted in the foreground of the old Government House, as the image above shows. The gardens in Sydney weren’t terribly productive as the coastal soil was ill-suited for introduced crops and, being a penal settlement, much of the produce was pilfered as it ripened. More fertile ground was found at Parramatta and in the Hawkesbury district where agriculture was more successful and some crops such as maize (corn) flourished.

The rations sound very basic and relentlessly monotonous to our palates but, for many of the recipients, would have been better than the diet they were used to in Britain. Colonists were remarkably adventurous and often creative with what was available to them. With rations alone, a variety of options were available. Salt meat could form the base of soups or stews, or be used to flavour rice gruel (congee style) or ‘pease’, as in pea and ham soup. Fresh greens, when available, would be added for flavour, variety and their nutritive quality. Pork was favoured over beef for its fatty layers which added flavour, helped keep meat from drying out and could be used to grease pans for frying or shortening pastry etc. Flour could be used for bread, damper (bread-cake cooked in campfire coals), while stale bread could be used to thicken or extend soups and stews. Flour could also be used for pastry, pies and puddings – ‘toad in the hole’ or Yorkshire pudding style.

Surgeon John White enjoyed a meal on a bush expedition in 1788. Having shot an assortment of wild birds,

We had our ducks picked, stuffed with some slices of salt beef, and roasted, and never did a repast seem more delicious; the salt beef, serving as a palatable substitute for the want of salt, gave it an agreeable relish.

April 24, 1788 White, John. Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales. 1790.

A maggotty start

Fresh food was always welcomed, but it wasn’t necessarily very practical. The ‘officers and gentlemen’ of the settlement attended a celebratory meal 225 years ago today – February 7, 1788 – after Governor Phillip read his Commissions to the people and thus ‘take possession of the colony in form’ (Tench). Avid diarist Lieutenant Ralph Clark (d.1794) wrote that:

… all the officers dinned with him on a cold collation but the Mutten which had been kild yesterday morning was full of maggots nothing will keep 24 hours in this country I find…

Clark, Ralph. The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-1792. February 7, 1788 (spelling & grammar remains unedited).

Clearly things improved for the next big celebration – the King’s birthday – fortunately occurring in winter, on June 4, 1788. Surgeon Worgan, something of a gourmand, detailed with great relish, the feast enjoyed at the Governor’s house

[At] about 2 o’Clock We sat down to a very good Entertainment, considering how far we are from Leaden-Hall Market, it consisted of Mutton, Pork, Ducks, Fowls, Fish, Kanguroo [sic], Sallads [sic], Pies & preserved Fruits… The Potables consisted of Port, Lisbon, Madeira, Teneriffe and good old English Porter, these went merrily round in Bumpers… We then gave three Huzza’s, as we had done indeed after every loyal Toast, The Band playing the whole Time… June 4, 1788

Worgan, George B. Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon. 1788.

Sources:

As cited above, plus:

Tench, Watkin (1759-1833). A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay. 1789. p65.