The curators at Sydney Living Museums have a phrase for it: ‘rabbit holing’, and at Rouse Hill House we’re particularly susceptible to it’s insidious power. You pick up an object, something catches your eye, and the next thing you know time has become abstract and you’re deep in 19th century newspapers unraveling connections. This week assistant curator Mel Flyte revisits the storeroom at Rouse Hill, and one of her favorite objects and the unexpected story it tells.

Tales from the storeroom

The opportunity to handle the objects in our collections is my favourite part of being a curator. I feel an enormous sense of privilege every time I hold an object. I like to refer to them as treasures, for often they are beautiful, rare, and valuable.

More commonly found in the Rouse Hill House collection stored in the old servant’s quarters, however, are objects of the everyday, the vernacular, the familiar, and the ordinary. Rusty farm equipment, boxes of nails, broken vases, empty jars, even tupperware. It may be tempting to see them as prosaic, but for me, these objects have their own poetic appeal, and often tell stories of enormous interest and importance.

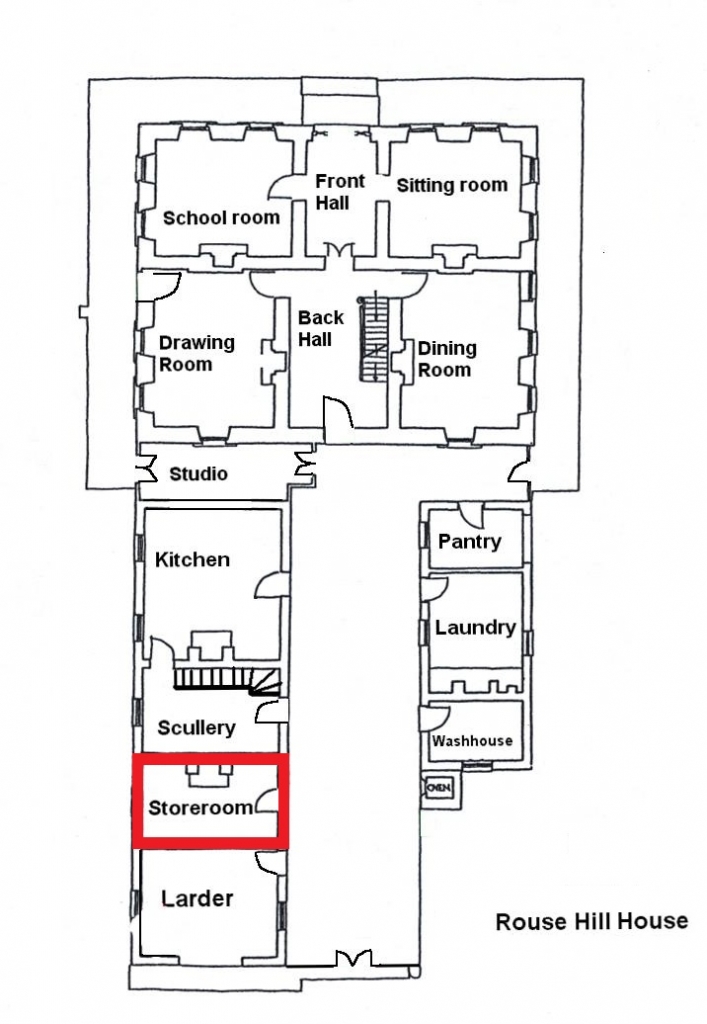

Plan of the ground floor of Rouse Hill House locating the storeroom in the main service wing

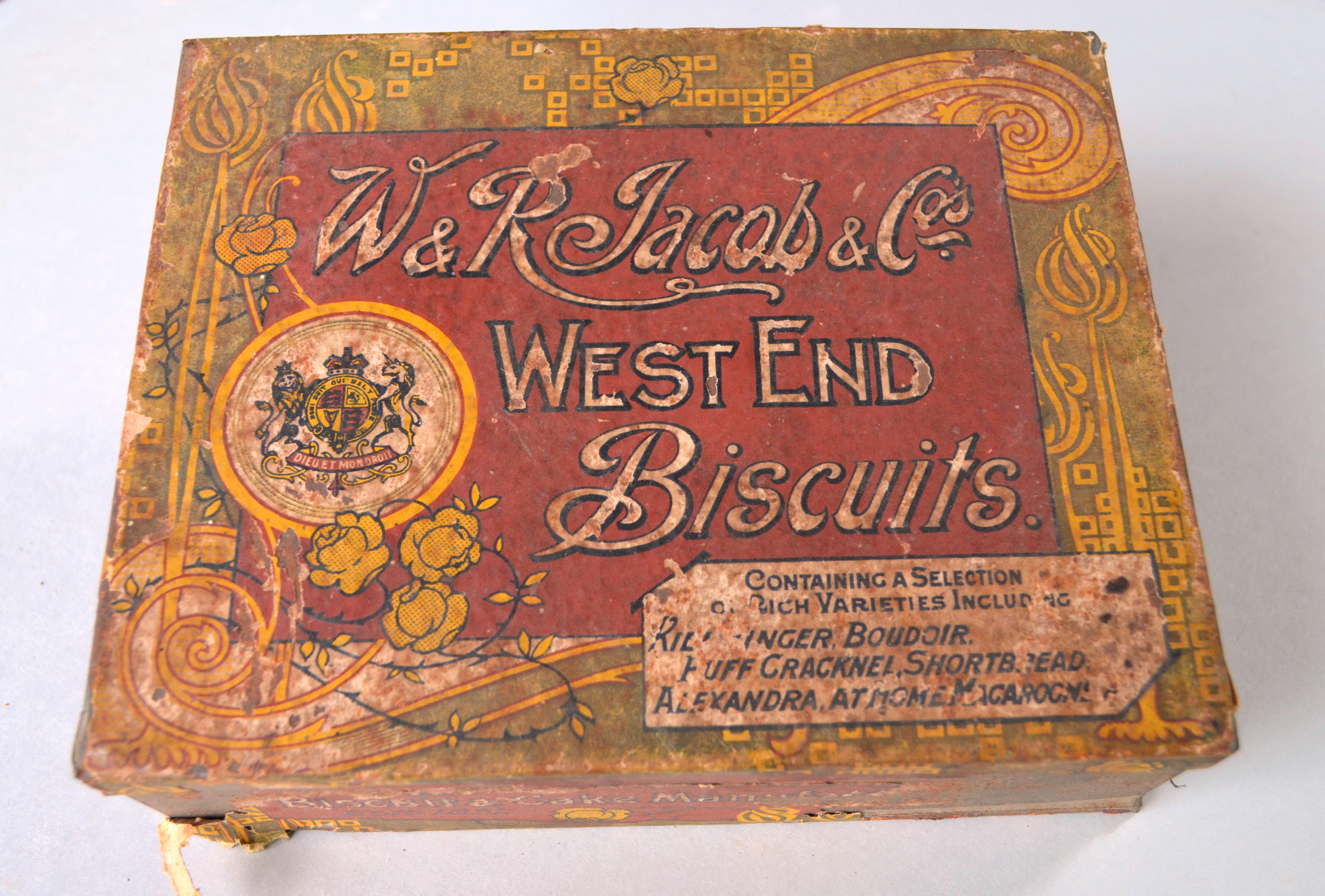

Take, for instance, this lovely little biscuit tin which caught my eye during a day of conservation cleaning in the storeroom, one of the rooms in the servant’s wing. Nestled in a larger cardboard box of miscellany, its glorious colours captured my attention.

W & R Jacob & Co. ‘West End Biscuits’ tin; Rouse Hill House collection. Photo © Mel Flyte for Sydney Living Museums

We rarely consider the wrappings in which our biscuits arrive today. We tear open the package and enjoy the contents with our tea. But this little box was a thing of beauty, an art-nouveau inspired treasure which once held an exotic range of ‘west end’ biscuits. I had to find out more!

A bit of research led me on an unexpected journey of discovery, with a surprising result – this little tin was linked to a momentous event in Irish history – the Easter Rising of 1916!

‘W & R Jacob, Biscuit and Cake manufacturer’

W & R Jacob, the maker of the biscuits, was an Irish biscuit-making firm based in Dublin. The Jacobs were Quakers who had fled England in the 17th century and settled in Ireland. Generations later, the Jacob family had established themselves as sea-biscuit producers, stocking the ships which sailed from Ireland with ‘hard tack’ – the staple diet of seafarers.

By 1851, brothers William Beale Jacob and Robert Jacob, inspired by the industrial revolution, decided to establish a “fancy” biscuit company in Co Waterford, which would produce a range of sweet, ‘shaped’ biscuits – a huge step up from hard-tack.

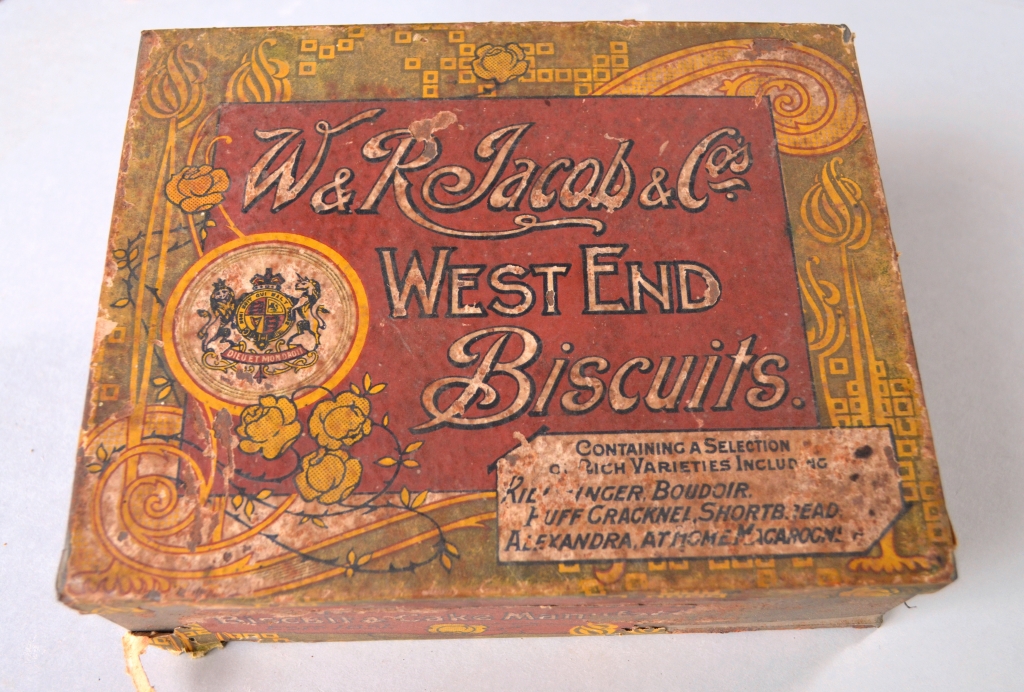

Detail of Jacobs Biscuits tin in the Rouse Hill House collection. Photo © Mel Flyte for Sydney Living Museums

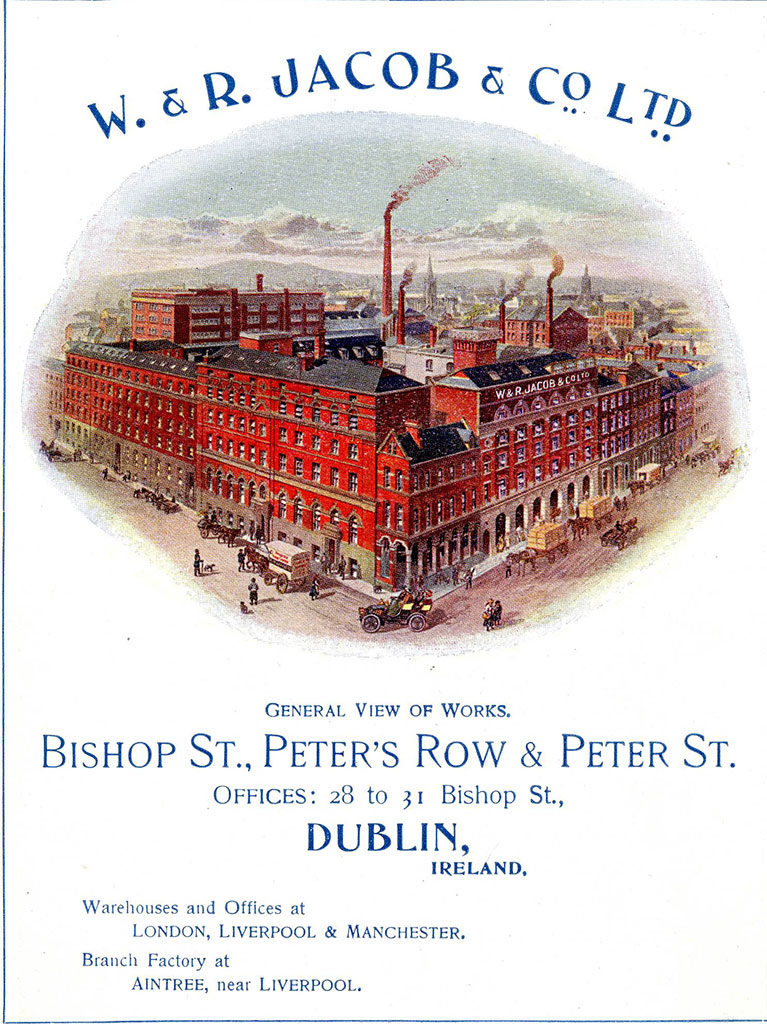

By 1853 the Jacob biscuit company was doing so well they relocated to Dublin, operating out of a factory in Peter’s Row, near The Liberties. The Liberties was a tenement area in Dublin where much of the workforce for the factory lived. The opening of the factory provided a good opportunity for work for many families in the area, as both men and women were employed. Within a few years, the factory had expanded to take up a whole city block.

The Jacobs factory in Dublin ca.1910, which covered an entire city block. Photo © Dublin City Council with permission

In fact, working for Jacob’s had many benefits. The company was known as a good employer, despite not having the highest wages for their staff. Within the factory, most of the workers were young women, known as ‘Jacob’s Girls’. Wages were paid based on age and length of service. Average wages in 1913 were as follows: older men were paid 28 shillings and 7 pence a week. Younger men and boys received 12 shillings and 2 pence. Bakehouse girls earned 8 shillings and 2 pence.[1] Boys could begin employment at age 14, but were usually let go by 19, however some men were kept on in positions such as drivers, cleaners, and factory caretakers.

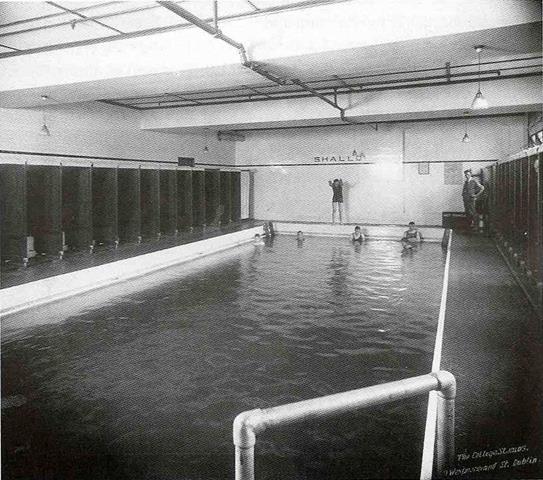

Working at the factory had other advantages – a canteen was located in the factory for worker’s lunches, with a good dinner costing only 2 pence. There was also a roof garden, swimming pool and recreation hall for games such as table tennis. An outdoor recreation field enabled workers to play cricket and football in factory teams. There was a factory choir, and classes offered in first aid, languages, sewing and handicrafts. Twice a year, employees could go on excursions organized by the Social and Entertainment Committee. To accommodate holidays for the staff, the factory shut down production for a two week period every August. Pension schemes were established, and ex-workers cared for. There was an on-site doctor and dentist, and a convalescent home for recovering workers to stay.

The factory played an important part in lives of many families in Dublin, and it was not uncommon for multiple generations of a family to all find employment at Jacob’s.

The pool for the workers at the Jacobs factory. Photo © www.jacobs1916.com

“West End” Selection

In terms of products, Jacobs produced around 60 varieties of biscuit, including their world renowned “Cream Cracker”, a unique invention introduced in 1885 and apparently a favourite of Prince Frederick Leopold of Prussia, who ordered 6 tins in 1893 [2].

Our lovely tin contained a mix of biscuits, including ‘Boudoir’, ‘Puff Cracknell’, shortbread, ‘Alexandra’, and the enigmatic ‘At Home Macaroons’. This particular mixed selection was named to associate it with the vibrant West End of London, evoking the glamour and prestige of that area.

The ‘West end’ biscuit selection. Detail of Jacobs biscuit tin in the Rouse Hill collection. Photo © Mel Flyte for Sydney Living Museums

Everyone loves a Puff Cracknell!

“JACOB AND CO’S. PUFF CRACKNELLS,which, by their extraordinary lightness and delicacy of texture, appeal to all connoisseurs,but are specially adapted for those who require the lightest and most easily digested food in an attractive and appetising form. Hobart agents W M Murdoch & Co. High class grocers.”

The Daily Post (Hobart), 3rd December 1908

Our new favourite biscuit names are the ‘At Home Macaroon’ and the ‘Puff Cracknell’. Another trip down the rabbit hole was in search of the latter. The general opinion is that that the light biscuit with the squeaky texture just doesn’t exist anymore. This description is by Betty Cross on a Scottish chatroom: “Puff cracknells were round in shape about 1″ thick and about 2″ in diameter. They must have consisted of only some sort of light flour or cornflour and water (they didn’t seem to have any fat in them) and when they were baked they like a crispy sort of compressed powder and had a depression in the centre which you filled with butter and lemon cheese. These were very much available after the war years but sadly these can’t be purchased now.” [3] Another writer – ‘Serabash’ – tells of his or her granny cutting them in half and filling them with mashed banana and dates. The Perth Sunday Times (18th December, 1932) also gives a quick recipe for a lemon filling:

New Lemon Filling For Puffed Cracknels.

The following filling can be quickly made for using in puff cracknels or baked pastry cases:- One tin of sweetened condensed milk (or one and one-third cups) half a cup of lemon juice, grated rind of one lemon.

Add lemon juice gradually to the milk and stir until combined, adding grated rind. Keep as cool as possible until used.

Biscuit tins themselves came about in 1861 after the passing of the Licensed Grocer’s Act [4]. This Act allowed groceries to be individually packaged and sold, rather than having to rely on your local grocer to package up your produce in the shop after he’d selected it and weighed in from bulk stock. The Act coincided with the removal of the duty on paper for printed labels, enabling decorative printed labels to be produced, like the one on our tin. The most exotic tin designs appeared in the early 20th century, but by the 1930s the production of most fancy tins had become too expensive, and so were reserved for the Christmas market (this trend continues to this day, especially with shortbreads).

Rebellion!

While Jacobs was providing a steady income for many workers, not everyone in Dublin was lucky enough to work in such good conditions. Growing unrest had been building in the city since 1911, when a series of lockouts had taken place as a result of workers attempting to unionise. Even Jacobs had taken part in locking out sections of its workforce who had refused to remove their union badges. Much of the push to unionise came from pro-republic groups. Opposition to British rule in Ireland was beginning to ferment.

By 1916, the situation was volatile. It was decided that a military uprising would take place to end British rule in Ireland during the Easter weekend. The rebellion was organized by members of the Irish Volunteers, the Irish Citizen Army, and the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

The Jacob’s factory, because of its size and strategic location, was chosen as a base for rebel action. On the 24th April – Easter Friday – when most of the 3000 strong Jacobs workforce had gone home for the weekend, a group of rebels stormed the building and took control, capturing the caretaker and the few staff left on site.

The rebels used sacks of biscuit-making flour to fortify their stronghold, and settled in for a drawn out guerilla-style confrontation with the British troops stationed in Dublin. The rebellion was not universally welcomed, however, and was viewed with ambivalence by the people of Dublin, particularly by many families employed at the factory. 388 Jacob’s workers were serving in the British Army in France at the time, and their families felt the rebellion was a disloyal act.

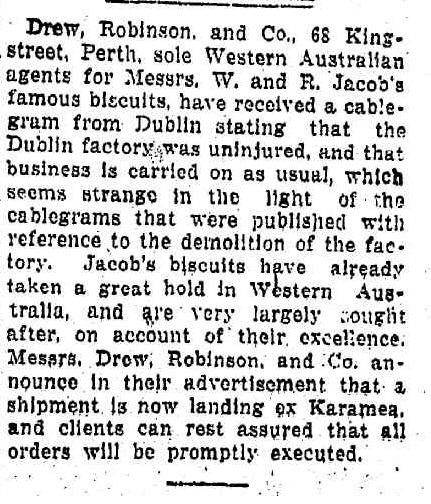

By April 29th, it was clear that the rebellion had failed. 64 rebels had been killed in the fighting, 134 British troops, and over 250 civilians. Much of Dublin had been damaged in the skirmishes. The rebels surrendered their hold on the factory and marched out to face their punishment. The leaders were executed and the uprising quashed. Within the factory, nearly 100 bombs had been left by the rebels, and needed to be dealt with before production could begin again. Despite reports the factory had been destroyed, biscuits were soon being produced again. [5]

Article relating to the Jacobs factory in the Perth Daily News, Saturday 3rd May, 1916, p.7

Life in Dublin went on again, but the Easter Rising was not forgotten. This year marks its centenary, and many commemorative events were held in Dublin. The rebellion was the largest uprising in Ireland since 1798, and began the long struggle for Irish independence from the British.

The Jacob’s factory remained a recognizable part of the Dublin skyline until the factory burned down in 1987. The National Archives of Ireland now stand on the site of the original factory. Another factory was built in the outer Dublin suburbs, but in 2009, after 156 years of biscuit production, Jacob’s biscuits closed its doors for good, ending a most significant chapter in Irish history.

I bet you never thought there’d be so much packed inside a little biscuit tin!

Further reading:

Further watching, dealing with the events of the Easter Rising is the Neflix Original series “Rebellion” (2016)

Notes

[1] www.jacobs1916.com

[2] www.jacobs1916.com

[3] http://discuss.glasgowguide.co.uk/lofiversion/index.php/t15611.html

[4] http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O22798/biscuit-tin-mcvitie-price/

[5] The GPO didn’t fare as well. It was almost completely destroyed by the British as they bombarded the rebels inside. By the end of the battle, only the façade still stood. Today the building has been rebuilt, and stands as a powerful symbol of Irish nationalism.