In these days of supermarkets, bakeries and bread makers we can easily forget how the simple act of baking bread has been a feature of life for thousands of years.

Long before Europeans arrived Indigenous peoples had used a range of native seeds, from grasses to shrubs and Bunya seeds, which were ground to a basic flour, usually to be baked on the coals. Some of these are finally being introduced to markets today, such as wattle seed. With the Europeans came domesticated wheat, rye, corn and other crops. In the early days of the colony when flour shortages were common invitations to dine at Government House apparently entailed diners bringing their own bread. One invitation however carried a further note –

“There will always be a roll for Mrs Macarthur”.

At Elizabeth Farm, first built in 1793 near Parramatta, bread was initially baked on site. With the establishment of local bakers it was soon a commodity bought in daily along with – perhaps surprisingly – eggs. The quantity bought in was considerable going by the household accounts, where over £7 a month (!!) was recorded in 1823. The description was likely for an order delivered daily, and included provisions for the estate workforce not just the family:

Paid [Richard] Longford’s for white bread biscuit and buns

2 brown bread from 6th march to april 1st – £7/10/5 ½Elizabeth Farm day book 1821 – 23 (SLNSW MP A3000) entry for April 5, 1823

The account lists both white and brown bread. Breakfast rolls were likely an exception, baked in small quantities before sunrise and served fresh and warm.

The dough box

In the kitchen at Elizabeth Farm is a distinctively-shaped, rustic table with deep, canted sides. It’s a reproduction of one of the earliest surviving pieces of colonial furniture, a ‘dough box’ from Camden Park. Though the original has long lost its central divider, it contained two deep compartments, one for holding dry flour, and one for the actual kneading the wet dough. The flat top provided a handy workspace. John Claudius Loudon describes these utilitarian boxes, which he terms a ‘kneading trough’, and as found in innumerable kitchens. Though the context for his description is for humble cottages, the ubiquitous dough box was found in the kitchens and bakeries of the very highest houses:

Design for a dough box, Fig 593 from J C Loudon, Encyclopaedia of Cottage Farm and Villa Architecture, 1842. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

One of the most economical of kitchen tables is that formed by the kneading trough… such tables are a good deal in use in the cottages and small farm houses in many parts of England. The cover, which, when on the trough, serves as a table or ironing board, either lifts off, or, being hinged, is placed so as went opened it may lean against a wall, when the trough is wanted to be used. Frequently a division is made in the centre of the trough, so that the dry flour can be kept in one compartment, and the dough made in the other. Sometimes there are three compartments, in order to keep separate two different kinds of flour or meal. The board forming the cover ought to be an inch and a half thick and always in one piece in order that neither dirt nor dust may drop through the joints.

They should never be painted, he added, as they were constantly being scoured clean after use, and if used for ironing the paint would quickly blister. In ‘The English Bread Book’ Eliza Acton writes of their use, emphasizing the paramount need for hygiene:

To make bread on a moderate scale, nothing further is required than a kneading-trough or tub, or a large earthenware pan, which is more easily than anything else kept clean and dry; a hair sieve for straining yeast occasionally, and one or two strong spoons. All wooden vessels used in preparing it, should be kept exclusively for the purpose, and be well scalded [in boiling water], dried thoroughly, and set away in a well ventilated, and not in a damp place, after every baking. They should also be wiped free from dust when again brought out for use.

The kneading-tub or pan should be of sufficient size and depth to contain the quantity of flour required for bread without being much more than half filled, as there should be space enough to knead the dough freely, without danger of throwing the flour over the edges, and also to allow for its rising.

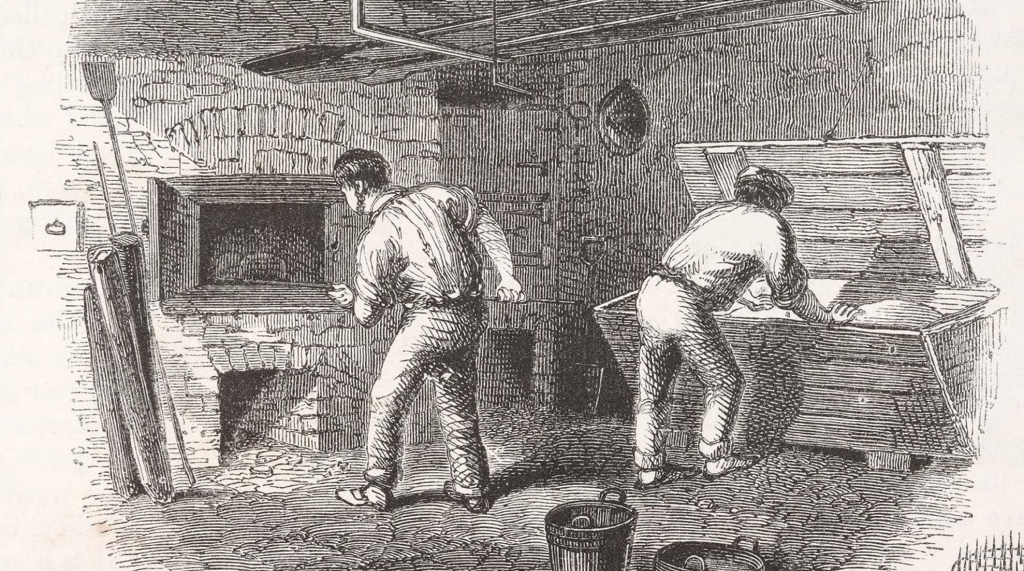

In this 1857 image you can see a (particularly deep) dough box in use to the right:

‘Baking oven and kneading trough’ (detail) from Charles Tomlinson, Illustrations of useful arts, manufactures, and trades, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, [1858]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums RB 331.76 TOM

Single compartment dough box in the cook house at Brickenden, Tasmania. Photo © Scott Hill

Dough box at Woolmers, Tasmania, with its lid closed. Photo © Scott Hill

Dough box at Woolmers Tasmania. Photo © Scott Hill

While this whopper (almost coffin-like in proportion) from Richmond Gaol, Tasmania (without its legs), could be used by 2 or 3 prisoners at once in preparing the gaol’s daily bread allocations:

Long dough box at Richmond Gaol, Tasmania. Photo © Scott Hill

All of these examples have detachable, rather than hinged lids. In 1835 when James and William Macarthur moved into Camden Park house, around an hour and a half South-west of Sydney, buying locally baked bread wasn’t an option so large quantities were baked there daily for many years, along with cakes and biscuits. In my next post I’ll look at the next stage in the baking process – and the very specific design of bread ovens.

“Bread to strengthen mans heart”, frontispiece in Eliza Acton, The English bread-book for domestic use, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, London, 1857. Google Books

A second serve

Eliza Acton The English Bread Book for domestic use adapted to families of every grade. London, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts. 1857

Read The English bread book online here.

J C Loudon An encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture. London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. 1842

Read the 1842 edition of the Encyclopaedia online here