Currently on show at the Museum of Sydney, ‘Demolished Sydney’ showcases the fate of several of Sydney’s iconic buildings. For eight decades one of these ruled among the most fashionable places to dine in the country for which it was named – the Australia Hotel.

To quote from the exhibition text, the hotel was one of Sydney’s major social and physical landmarks “for 80 years. When it opened on Castlereagh Street in 1891, its Belle Epoque opulence matched that of the best hotels in Europe and America. An Art Deco refurbishment and extension on Martin Place in 1936 ensured it remained the place to see and be seen until the end of the 1960s.”

Detail of Luncheons and Private Functions menu from the Hotel Australia, Sydney, circa 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection Sydney Living Museums

Location is everything!

The hotel was built in a prime location: near the Theatre Royal and the lively Rowe Street laneway, popular with Sydney’s theatre and Bohemian set. When opened its lavish style certainly impressed its clientele:

The grand staircase leading to the first floor is of marble, the steps of white Sicilian, and that used for the handrail and balusters of deep Rouge and Dove, from the Belgian quarries. By it we reach the main corridor, 16 foot wide, massive with Doric columns, and richly lighted, like the staircases, by windows of stained-glass. This corridor gives access to the principal dining hall, 100×40×25 foot. Here the columns are Corinthian, fluted and gracefully carved, and setting off the proportions and height of the apartment. Remarkable taste and judgement are displayed in the magnificent appointments of this dining hall – the mirrors, fitted at the centre with sprays of electric light, that line the walls, the appropriate chairs and tables and luxurious carpeting; but, most of all, the imposing carved screen, like a cathedral reredos, which supports which separates the wine and plate stores from the hall proper. This screen is stained Walnut, in the style of the Italian Renaissance.

The ladies’ drawing room also opens of the main corridor. It is 50 x 24 ft., but so subdivided by screens as to practically form three apartments. The furniture and decorations are exceedingly light and delicate, the style being that of Louis Sezie [sic]. There is a daintiness about the upholstering and furnishing here that seems in exquisite taste and keeping with the purpose to which this room is to be devoted. Other rooms here are the ladies’ tearoom music room, and private writing room, besides two private dining rooms which are fitted with skillful and harmonious effect.

‘THE AUSTRALIA HOTEL’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday June 20th, 1891

And on it went. In the 1930s these dining and reception rooms were remodeled in the very different Art Deco style.

The exhibition contains several menu cards from the Hotel’s various dining and reception rooms, and cocktail bars “which were updated in the 1960s to compete with the American-style hotels of the postwar building boom.” The revamp included “the Bevery, a snack bar serving deluxe hamburgers.”

The full menu

Cover for the full menu for The Hotel Australia, Sydney, circa 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Full menu for The Hotel Australia, Sydney, circa 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

…and the cocktail and buffet menus

Cover for the Cocktail Buffet Menu from The Hotel Australia, Sydney, ca.1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Cocktail buffet menu from The Hotel Australia, Sydney, ca1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

But lets join Frank and Patricia over in the Amethyst Room…

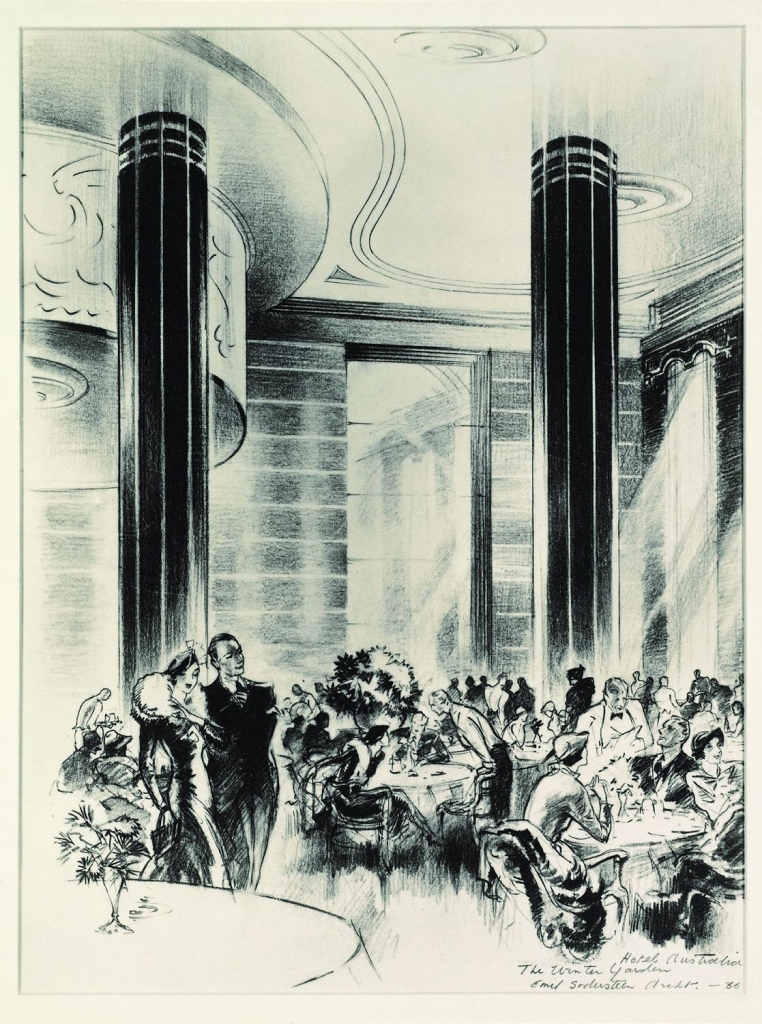

The Wintergarden at the Hotel Australia. Robert Emerson, ca1934. State Library of NSW PXD 499, F14

Given a major refit in the Art Deco style and renamed ‘The Amethyst Room’ – along with the geologically inclined Jade, Sapphire, Carnelian and Opal rooms – the Wintergarden was one of several reception rooms at the hotel. One function held there was the 1963 celebrity wedding of TV’s ‘Pick-a-box’ winner and Victoria Cross recipient Frank Partridge to Patricia Dunlop:

The reception for 256 guests was at the Australia Hotel, in the Amethyst Room, fondly remembered as the Wintergarden by millions of Australians. A small ornamental fountain played in front of the bridal table, picturesque with silver candelabra. Three shallow steps led from the fountain on to the dance floor where the magnificent three-tiered wedding cake stood. It was made by the bride’s mother.

Rich fare

The menu was Hors d’oeuvre a la Russe, Fruit Cocktail, Chicken Maréchale (chicken crumbed, fried, and served hot with ham, asparagus, peas, beans,and potatoes), Pavlova Chantilly with crushed nuts and ice-cream, coffee, and after-dinner mints. Such a mammoth function was a trifle to the bride’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. R. S. Dunlop, of Turramurra, N.S.W.‘Crowds flock to TV wedding’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, Wed 6 Mar 1963

The dishes can be seen in the various menus printed only a few years later. Reading these menus today its hard not to think of them today as being, well, less than special. Still, even cocktail frankfurts had to start somewhere….

Cover of the Luncheons and Private Functions menu from the Hotel Australia, Sydney, circa 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Luncheons and Private Functions menu from the Hotel Australia, Sydney, circa 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums.

‘Chicken Maréchale’ ($2.75, and defined for the reader as served with asparagus tips, potato croquettes and peas) for example has a long history in French haute cuisine but suffers somewhat when described as ‘crumbed fried chicken’. What was once a dish served on very high tables – think also of the Russian chicken Kiev – sounds today uncomfortably like fast food straight from the supermarket freezer…

To start: Hors d’oeuvres a la Russe

Frank and Patricia’s many guests also enjoyed a seafood entree – ‘hors d’oeuvres a la Russe‘. This was a flamboyant seafood dish, defined in this 1930s article:

MIDNIGHT SUPPER PARTIES – Climax of a Festive Evening

Perhaps the most important of the cold hors d’oeuvres is the one called hors d’oeuvres a la Russe. This is a combination of caviar, lobster, shrimp, crabmeat, and anchovy, with anything added to these one’s fancy suggests. It is necessary that this dish be extremely well chilled. It should therefore be served on an ice platter or tray, if possible.

Put shaved ice inside the tray, and in the centre pack a glass bowl large enough to hold the required amount of caviar. This is kept steady in its place by the shaved ice, tightly packed. At each end of the platter set a small dish in the shaved ice. Fill one with mayonnaise and the other with horseradish, or with a cocktail sauce, if preferred. Cover the surface of the shaved ice with crisp lettuce leaves. Around the centre make nests of finely shredded lettuce, and in these nests, in separate groups, put anchovies and marinated lobster, shrimp, and crabmeat. Arranging them with care. Decorate the edge of the platter with black and green olives, lemon quarters and radishes, placing them in alternate groups.

‘Homecraft’ section, The Mail (Adelaide), Sat 8th November, 1930

Caviar certainly gives it its Russian air. What aren’t mentioned are small toasts to eat the individual meats on. I have to suspect that this dish with its shredded lettuce nests lurks somewhere in the mixed DNA of the modern prawn cocktail, whose ancestor with its tomato-based sauce appeared way back in the late 1800s.

The end of an era

Well the exhibition isn’t called ‘Demolished Sydney’ for nothing!

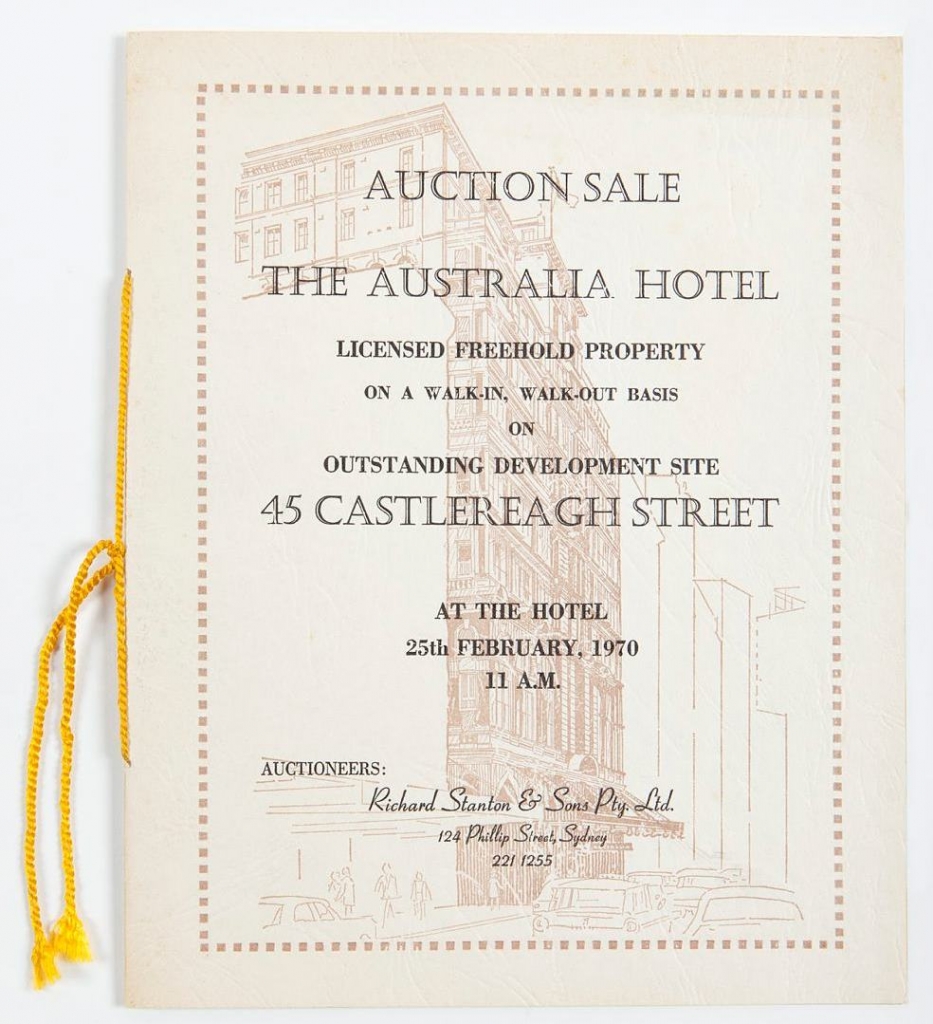

The Hotel Australia’s days were numbered, and it was put up for auction and the site’s redevelopment, with a cord-bound sale catalogue that looks all the world like a classy hotel menu: “…as new city hotels were constructed in the 1960s, the Hotel Australia went into decline, unable to compete with international ‘jet set’ standards. The last guests checked out in June 1971, and most of the buildings on the block were demolished to make way for Harry Seidler’s award-winning MLC centre.” Ironically, many of the dishes on the hotels menus survive and are served to lunchtime dinners in the food court. As the focus of Sydney’s night life continued to migrate to Kings Cross with its restaurants, bars and nightclubs, the city CBD instead became a zone dedicated to business – an issue that planners and councilors battle to this day.

Hotel Australia auction catalogue. Richard Stanton & Sons (auctioneers), 25th February 1970. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Come and visit

Curated by Dr Nicola Teffler, ‘Demolished Sydney’ is on at the Museum of Sydney until April 17th, 2017. Full details are here, and there is a newly announced series of talks.