One of the things that’s surprised me most about colonial gardens is just how exotic they were. I like to think of myself as relatively broad-palated, but when I stumbled across a list of fruits available in NSW in 1824 my jaw dropped. Apples, pears, peaches, nectarines, apricots, cherries and plums. So far so expected. But the Chilean cherimolia and alligator pear – what on earth were those?

I’m Helen Curran, an assistant curator at Sydney Living Museums, and I’ll be guest blogging on The Cook and the Curator while Jacqui’s taking a well-earned breather. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be examining the secret lives of some of the lesser-known fruits and vegetables growing in our kitchen gardens.

Deliciousness itself

Colonial botanist Charles Fraser, the first superintendent of Sydney’s Botanic Gardens, described it as ‘one of the finest fruits in the world’. For Mark Twain it was ‘the most delicious fruit known to men’.

The source of this enthusiastic 19th-century hyperbole was a fruit native to the Central Andes, the cherimoya. (This is the ‘cherimolia of Chili’ listed in the Sydney Gazette in 1824; it is also sometimes spelled chirimoya.) Its reputation as ‘deliciousness itself’ comes from its unique flavour, often described as a mixture of pineapple and banana. Some taste papaya, coconut, strawberry and mango too.

The cherimoya looks a bit like a smoother version of an artichoke. It yields a creamy, fragrant, ivory-coloured flesh, which gave rise to another of its common names, the custard apple. And here’s where things start to get confusing.

An early exchange

The custard apple tree (rear) in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House. You can find it on the opposite side of the shed to the beehives and water tank, by the pineapples and cherry guava. Photo Helen Curran © Sydney Living Museums

In October 1847, William Charles Wentworth sent a bearer the 7 or so kilometres from his estate at Vaucluse to the famous gardens at Elizabeth Bay House with a note requesting the custard apple that William Sharp Macleay, its owner, had been ‘good enough to promise’.

The cherimoya is one of several dozen species in the Annona genus, which have been cultivated for their fruit by the peoples of Central and South America since ancient times. Today, the genus is found throughout the tropics and subtropics, either by origin or introduction. ‘Custard apple’ is something of a catch-all name, applied to the cherimoya and any or all its cousins.

Throughout the 19th century, then, ‘custard apple’ and ‘cherimoya’ often described the same fruit. Interestingly, however, the Gazette lists each separately. So what was the custard apple Wentworth sent for? And is it the same as the custard apples we find at market stalls today?

Sweetsops and sugar-apples

In 1828, Charles Fraser listed Annona cherimola, the cherimoya, among the plants growing in Sydney’s Botanic Garden. But in the 1831 Australian Almanack, he writes that the ‘cherimoya of Peru’ had yet to flower in the colony. A second species in his 1828 list, Annona squamosa, is likely to be the Gazette’s custard apple, and perhaps Wentworth’s. Much lumpier than the cherimoya, it’s also known as the sweetsop, or sugar-apple.

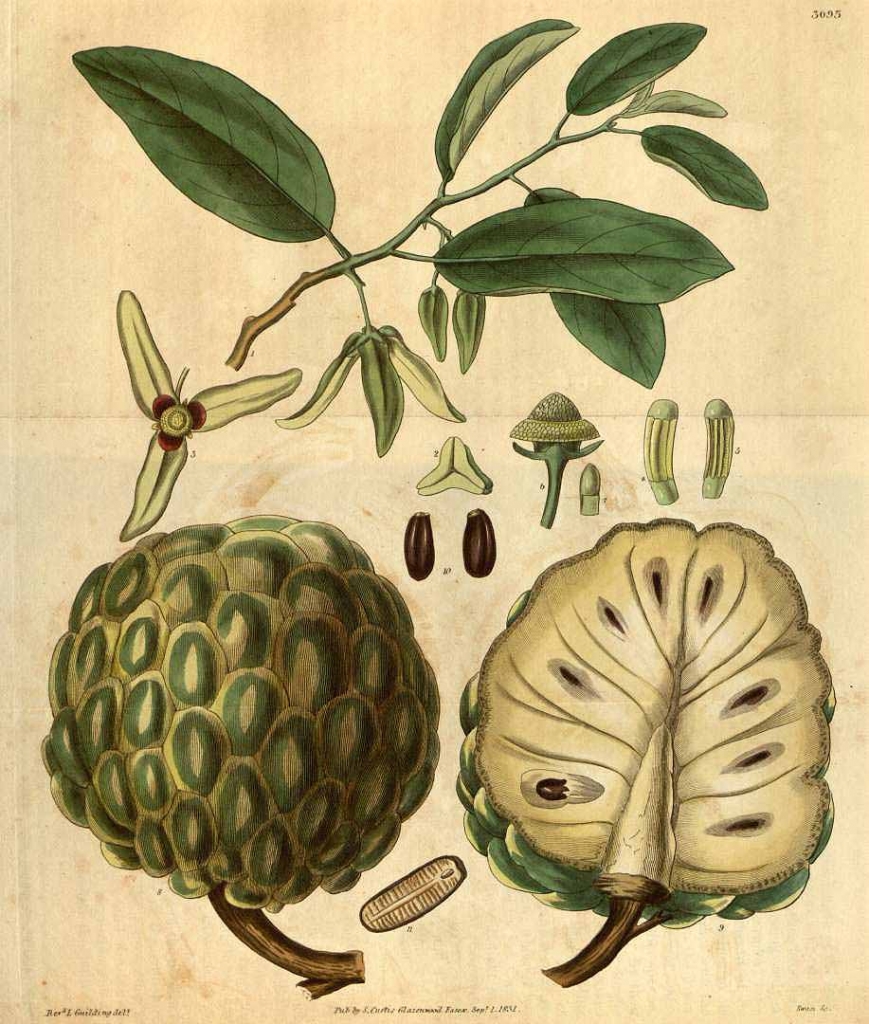

Colour plate of a sugar-apple or sweetsop (Annona squamosa) in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 1831. Image courtesy Missouri Botanical Garden

Though the cherimoya appears in 19th-century nursery lists from NSW, it does not seem to have flourished, even in the tropical north, where its relative the sugar-apple did so well.[1] A clue to this lies in its name, which comes from the Quechuan word chirimuya (literally, ‘cold seeds’); the cherimoya thrives in the high valleys of the Andes but not at lower elevations.

This unhappy fact led an American grower to cross the cherimoya with a sugar-apple in 1908 – combining the deliciousness of the first with the second’s ability to grow at sea level. According to Custard Apples Australia, today’s commercial varieties are likely to be the hybrid he produced: Annona × atemoya.

Chalk, cheese and cherimoyas

Despite the confusion, clued-up 19th-century writers were in no doubt about the superiority of the cherimoya over its relatives. Here’s the Geelong Advertiser setting matters straight in 1868:

We beg to inform our able contemporary the Australasian, that it is in error in stating ‘the cherimoya or custard apple is showing for flower.’ The chirimoya (not cherimoya), is as distinct from the West India custard apple as chalk is from cheese – it is a distinct fruit. The latter is nothing but a congeries [mass] of seeds, with a small quantity of pulp and juice, good in its way for lack of better; but the former, the chirimoya, is all throughout the most delicious pulp or soft flesh, melting in the mouth, and forcing the juice out so that a napkin is required almost to be held under the chin, and having sometimes one or two seeds in its centre, and often none … But it has not yet been raised in this colony.

All this makes it an intriguing question as to what, exactly, Godfrey Mundy sampled on his goggle-eyed visit to Sydney in 1846. Served a sumptuous meal at a private residence, Mundy feasted on local snapper, wallaby tail soup, kangaroo and wonga wonga pigeon. The menu then moved towards the exotic – ‘a dessert of plantains and loquots, guavas and mandarine oranges, pomegranates and cherimoyas’.

Forbidden fruit

Whatever Mundy sank his teeth into, a cherimoya or one of its relatives, his experience illustrates the fact that custard apples were a fruit reserved for the tables of the colonial elite.

Back, then, to William Charles Wentworth and the messenger entrusted with bringing him the custard apple from Elizabeth Bay. In all likelihood, Wentworth was after a seedling … but what if it had been a basket of fruit instead? Would the messenger have made the journey back to Vaucluse without succumbing to the tantalising fragrance of this most delicious of fruits? Or would he have taken the chance that his master, who was also fond of melons and pineapples, would not notice one of the missing delicacies?

I like to imagine him, this unnamed, unknown bearer, eating a custard apple by the water at one of the bays along the coast. He eats with curiosity, then abandon, as that delicious, illicit juice runs unheeded down his chin.

View of harbour from South Head shewing the entrance, Watsons Bay, and Vaucluse by Conrad Martens, 1848. Sydney Living Museums V88/572

[1] In 1875, a reader asked The Queenslander which ‘Custard Apple’ variety had done best, ‘the Sweetsop, Soursop [Annona muricata], or Chirimoya’. The newspaper responded: ‘Sweetsop has borne best here; the other varieties, so far as tried, have gained the reputation of being poor bearers; they need further and systematic trial.’