Many Australians today have departed from the conventional trilogy of ham and turkey and plum pudding, in favour of seafood or barbecues with salad, and a cold dessert such as trifle or pavlova. But how ‘traditional’ is our perceived idea of Christmas fare?

Tastes, trends and titles

Christmas plum pudding certainly takes the cake (excuse the pun) as the stalwart hero dish at Christmas, as Christmas cake per se is a late entry. Until Victorian times, the rich fruit cake was reserved for Twelfth Night, on January 6. And until the 1840s ‘Christmas’ pudding was plain old ‘plum pudding’ served not only at Christmas, but throughout the winter months. Cookery author Elisa Acton is credited with ‘Christening’ it ‘Christmas plum pudding’ in her cook book, Modern cookery for Private Families in 1845.

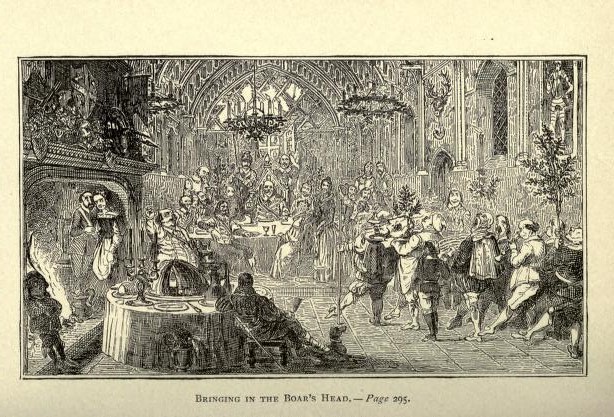

Similarly, ham and turkey were not limited to Christmas, served on many other celebratory occasions, and were alternatives or additions to a wider variety of options such as roast beef or pork with its coat of crackling, goose and various other fowl and game birds. And once upon a time, brawn made from a boar’s head was part of the festive repertoire.

‘Bringing in the boar’s head’ in The Book of Christmas (1888) by Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrated by Robert Seymour https://archive.org/details/bookofchristmas00herviala/page/n351

Whose Christmas?

It has been said that Charles Dickens ‘invented’ Christmas, which is of course a falsity (see discussions here, here and here), however many of the Christmas ‘traditions’ that dominate popular perception took shape in the Dickensian era.

Christmas Dinner, in ‘The book of Christmas’ frontispiece (1837). Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrations by Robert Seymour. Image source The British Library, B20070 97

‘A feathered phenomenon’

Dickens’ A Christmas Carol published in 1843, is one of the author’s best known works, and a favourite for the gastronomic historian, for the evocative description of the Cratchit family’s Christmas day dinner. It is interesting to note that goose prevailed as the festive bird on the Cratchit’s table. Goose may be seen as exotic today, but turkey carried more prestige at the time; the goose was a device used by Dickens to characterise the family’s impoverished means:

‘Master Peter, and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course—and in truth it was something very like it in that house…

Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by [sage and onion stuffing], apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family…’

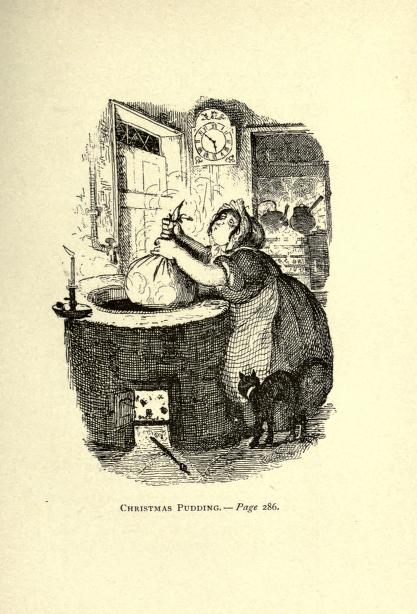

‘Christmas Pudding’ in The Book of Christmas (1888) by Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrated by Robert Seymour https://archive.org/details/bookofchristmas00herviala/page/n341

The proof in the pudding

Christmas plum pudding was of prime importance to the event, causing much angst for Mrs Cratchit:

‘Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose! … All sorts of horrors were supposed.

You can almost smell it cooking, from Dickens’ compelling commentary:

‘A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastry-cook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding!’

But all was well, for this poor but blessed family when:

‘Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.’

And her husband declared it ‘the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage’.

‘The Norfolk Coach’ in ‘The book of Christmas’ (1837). Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrations by Robert Seymour. Image source The British Library, B20070 93

Drawing from the past

Predating A Christmas Carol is The Book of Christmas by Hervey, Thomas Kibble first published in 1837. It gives far more comprehensive detail of the ‘customs, ceremonies, traditions, superstitions, fun, feeling and festivities of the Christmas season’, from St Thomas’s Day on December 21, through to St Distaff’s Day on January 7. It also describes ‘Old Christmas’ (pp. 46-47) with a ballad recalling times when,

‘the cooks shall be busied by day and by night, in roasting and boiling for taste and delight… Plum-pudding, goose, capon, minc’d pies and roast beef.’

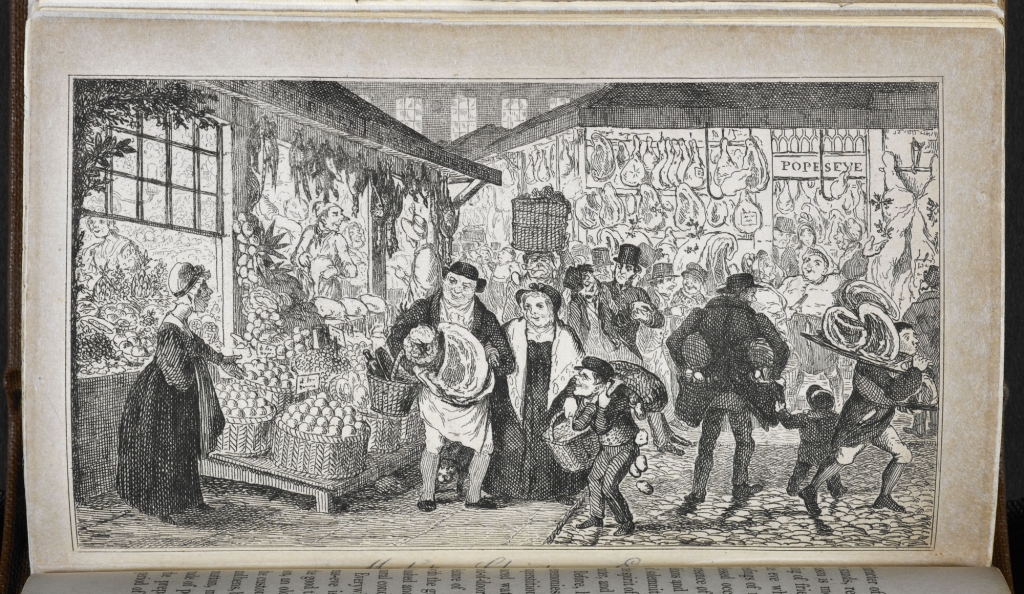

Kibble’s The Book of Christmas is richly illustrated with drawings by Robert Seymour, and food is central to many of the drawings throughout the book, many of which make strong statements about Christmas as a time of ‘cheer’. (Seymour also worked on Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, but sadly took his own life in 1838, before completing the commission).

‘Market – Christmas Eve’, in ‘The book of Christmas’ (1837). Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrations by Robert Seymour. Image source The British Library, B20070 96

‘Market – Christmas Eve’ perpetuates the notion of abundance and wealth, as we see well-fed customers tempted by a cornucopia of hams, fowls, fruit, potatoes and prized barons of beef. Interestingly there is no mention of ham as festive fare in A Christmas Carol or The Book of Christmas, but brawn survives in Scrooge’s ghostly fantasies. We can presume that the baskets of fruit are oranges, which were a luxury item in England in the 1800s, imported from Italy or Spain.

Gate of the “Old English Gentleman” in ‘The book of Christmas’ (1837). Hervey Thomas Kibble, illustrations by Robert Seymour. Image source The British Library, B20070 92

In stark contrast is the depiction of a paltry offerings for the poor and infirm gathering at the ‘Gate of the “Old English Gentleman”‘, reminding readers of the need for charity, particularly in the bleak wintertime.

It is little wonder that despite its convict associations, Australia was a place of wonder rather than dread, with local oranges, lemons, strawberries, apricots, plums, mulberries, cherries, loquats; fresh beans, peas, carrots, leeks and so on; ducks, geese, turkeys, fowls, pigeons; pork, mutton, beef and veal available from the Sydney markets (The Colonist, 14 December, 1839).