Kim Connor is currently undertaking an internship at Hyde Park barracks as part of her research project ‘Feeding the confined’ for her honours studies in archaeology at Sydney University. Kim’s particular interest is the diet of the women at Hyde Park barracks when it was the Immigration Depot and the Destitute Asylum between 1848 and 1886. Kim is our guest author this week, as with true gastronomic gusto, she not only reads about the types of food that the women ate, and how it was prepared, she attempts to recreate some of the food to support her thesis. What was the food like? Was it enough? And for today’s story – just how bad does bread and dripping taste?

A pound per day

The first thing that I needed to figure out was the bread because it was the eaten with every meal of the day. Each woman in the institutions received a pound of bread per day, or about 450g of bread. That’s roughly two thirds of a modern loaf of bread per person, per day!

Even though bread had been baked on-site during the convict period, it was bought in for the Asylum and the Depot. Fresh bread would have arrived at the barracks daily in two pound loaves, and each woman took a whole loaf every other day [1]. Even if that meant that your bread was a bit stale on the second day, I guess it meant that you could decide when and how you wanted to eat it.

In the early years of the Immigration Depot (which opened in 1848) the bread was probably wholemeal, because the doctor specifically ordered white loaves for people who were sick [2]. By the late 1860s, though, the Depot and the Destitute Asylum were only being provided with 1st quality bread which would have been white [3].

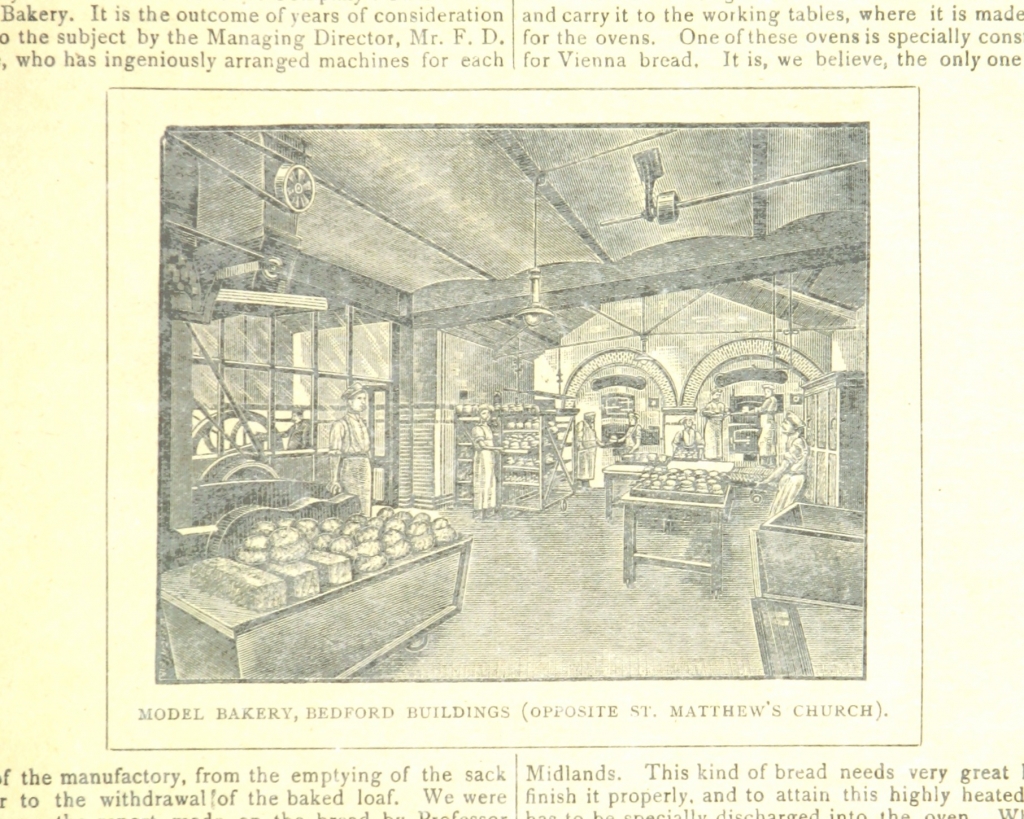

Model bakery, in “Where to Buy at Cheltenham. An Illustrated trades’ review, by the editor the “Agents’ Guide,” etc.’, 1890 p.37 by The British Library. Licensed under no known copyright restrictions.

Industrial versus home-made bread

At the beginning of the 19th century, baker’s bread was produced in much the same way as if you were making it at home, just on a larger scale. By the end of the century, though, the trade had undergone huge changes and industrialisation of the bread making process was well underway.

In the picture above you can see a large bakery in 1890 decked out with steam ovens on the back wall, and some bakeries would also have mechanical mixing machines. At the same time, the loaves on the table in the foreground are a mixture of the new square loaves, made in tins, and the more traditional cottage loaf which is shaped by hand.

Vienna Bread: Small Bakers and Hotels.

Quantities. – 2 ozs. yeast; 1 quart water; 1 quart milk; 1 oz. sugar; 1 oz. salt; and 9 lbs. finest Hungarian flour. Put in a sponge, with the milk and water at 90 degs. (Fahr.), yeast sugar, and flour to make a batter sponge. Let this rise and fall, and then make the dough. Powder the salt on to the sponge, and mix in with enough flour to make a light dough. It will be ready for moulding in an hour.

The Baker’s Guide and Practical Assistant (1899) [4]

In spite of that, even at the end of the century many of the recipes professional bakers used would have been recognisable to a home baker. You can see that the recipe above, from The Baker’s Guide and Practical Assistant (1899) isn’t that different from Eliza Acton’s domestic recipe:

Good Family Bread

Flour, a quartern, or half gallon (3 lbs.); solid brewer’s yeast, one tablespoonful; or German yeast, nearly one ounce; warm milk and water, or water only, one pint and a quarter to one pint and a half. When made by setting a sponge, to be left to rise for an hour, or more if needed, then made lightly into two loaves, sent to the oven from an hour to an hour and a quarter, or baked in one loaf from one hour and a half to two hours.

The English Bread-Book for Domestic Use (1857) [5]

The bread for the Destitute Asylum and the Immigration Depot was brought in from commercial bakers, but it was still a lot closer to home-made bread than the mass-produced, pre-sliced loaves that you can buy in the supermarket today.

Two-pound loaves made with an Eliza Acton recipe 1857 (recipe below). Photo © Kim Connors

But what is German yeast?

Before the invention of dried yeast in the early 20th century, bakers used a variety of different methods for leavening their bread. Sourdough bread, which used a starter made from wild yeasts is one of the oldest and most well-known methods, but bakers could also keep a bit of the dough for the next batch, which is called ‘old dough’, make their own mash from hops or potatoes, or use brewer’s yeast.

At the end of the 18th century, Dutch brewers and distillers began to sell the yeast left over from brewing in small, solid cakes, and the process soon spread to Germany where J.H Tebbenhoff was an early adopter [6]. By 1846 Australian newspapers were reporting that ‘German yeast’ was being imported into England from Rotterdam, and that it was becoming “a good deal used” [7]. Nowadays we call this fresh or compressed yeast, and you can buy it from good grocers.

Fresh yeast, referred to in the 19th-century as ‘German’ yeast. Photo © Kim Connors

Recreating 19th-century bread

I used Eliza Acton’s recipe for ‘Good Family Bread’ to make my bread (recipe below). It makes soft, delicious white bread that is perfect for sandwiches. You do have to add some salt, which has been forgotten in the original recipe and I’ve scaled it down to make two x 2 pound loaves, just like they had at Hyde Park Barracks. If you really want to enjoy it the way that the women did, try it with dripping and a well brewed cup of tea!

Breakfast and supper fare in the Immigration Depot and the Destitute Asylum (1848-1886): Bread with dripping (the fat skimmed from the soup) and tea. Photo © Kim Connors

Good family bread

Ingredients

- 1400g strong bread flour

- 24g fresh yeast

- 200ml milk, lukewarm

- 525ml water, lukewarm

- 27g salt

Note

This recipe is based on Eliza Acton’s ‘Good Family Bread’ (1857). It makes soft, delicious white bread that is perfect for sandwiches. You do have to add some salt, which has been forgotten in the original recipe.

Directions

[1] In response to Q2323-2324 NSWLAVP, Second Report of the Commission Appointed to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Working and Management of the Public Charities of the Colony (Sydney: Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1874), 75.

[2] For example, State Records NSW: NRS 5239, [9/6192] Item 49/1515.

[3] Frederic King, “Contracts for Bread, Meat, Groceries &c. For the Government Asylums at Sydney, Parramatta, Liverpool, and Port Macquarie,” NSW Government Gazette, October 27, 1868, No. 264 edition; Frederic King, “Contracts for Bread, Meat, and Groceries for the Government Asylum at Sydney,” New South Wales Government Gazette, February 18, 1870; State Records NSW: NRS 5239, Item 57/1891.

[4] John Blandy, The Bakers Guide And Practical Assistant To The Art Of Bread-Making In All Its Branches, 4th Ed. (London, 1899), 139, http://archive.org/details/TheBakersGuideAndPracticalAssistant.

[5] Eliza Acton, The English Bread-Book for Domestic Use (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, 1857), 134–35.

[6] J. Stewart Harrison, “Food and Fodder Yeasts,” in The Yeasts: Yeast Technology, ed. Anthony H. Rose and J. Stewart Harrison, 2nd ed. (London: Academic Press, 1993), 402.

[7] “Tropical Australia,” The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, June 20, 1846, 3.

Print recipe

Print recipe