One of the dishes that features in the 1859 Macleay menu created quite a discussion this week – pate de pigeon. Its a prime example of how language changes, and how you can’t always take what’s written at face value.

Recipes for pigeon are found throughout 19th-century cookbooks. Those available here feature both imported and local birds. Edward Abbott’s ‘English and Australian Cookery Book’ (1864, our first locally authored cookbook) has three pigeon recipes: Pigeons compote (essentially pigeons stuffed with breadcrumbs, egg, chopped bacon, parsley, onion and nutmeg , larded and browned in a pan then simmered in stock which is later thickened into a gravy); stewed in a brown sauce (“excellent”) and, for wild pigeons (similarly stuffed, larded and served with a sauce), which he also recommends more simply grilled and served with butter and dusted with cayenne pepper.

Leucosarcia Picata (Wonga-wonga Pigeon), from Birds of Australia, John Gould, 1840-1848. National Library of Australia

We’ve often referred to a handwritten menu of a dinner given by William Sharp Macleay of Elizabeth Bay House in 1859. We used it when recreating the grand dinner setting you may have seen in the Eat Your History: A Shared Table exhibition. In the menu ‘pate de pigeon’ is listed as a savoury dish in the meal’s second course. Its a bit of a puzzle though…

Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book (6th edition, 1905) lists 5 recipes for pigeon – pigeon pie, pigeon and steak pie, braized or sauteed pigeon and the more fanciful ‘pigeons a la Neapolitana’ (but more of that later). By this time imported pigeon were readily available, and often kept domestically. She also includes a recipe for wild Wonga pigeon, which she stuffs with a simple breadcrumb and butter stuffing then roasts with lemon juice – basted frequently.

Pigeon it seems went the way of the rabbit, associated with depression food and wartime rations, and it fell from favour for many years. Today Pigeon is a slowly growing industry, starting to appear in cooking shows and recipe books as an alternative to quail. The pigeon used for the table isn’t the same that you see fluttering around your city streets (a misconception that certainly hasn’t helped the image of squab) but particular breeds kept for their plump meat – especially the Red Carneau and the White King. Today squab, or young pigeon, is ready for market when it reaches around 26-30 days old, just about to start flying, and weighs around half a kilo. Unlike many birds, both parents feed the young, which speeds up their growth rate significantly. But where do you keep your pigeons? Why in a pigeon cote of course!

A rustic penthouse a la Belgenny

Pigeon houses – or pigeon cotes – appear quite early in the colony, and you see them listed as assets in farm sale and lease notices. At Belgenny Farm, once the home farm of the Macarthur’s Camden Park estate, a rather charming rustic pigeon house still stands in front of the farm buildings. For many years it supported the belief that rapid communications between there and Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta was by carrier pigeon! In reality it’s an endearing but long-held myth, that we occasionally still hear from visitors at Elizabeth Farm today. Talking with Dr Cameron Archer, head of the Belgenny Farm Trust, he explains its very practical purpose – not for letters but for a far more prosaic vermin control. The long building you can see in the background of the photo is the granary, and the pigeons were used to clean up spilled grain that would otherwise attract rats and mice. And no doubt some of the pigeons also made their way to the kitchen.

Pigeon house at Belgenny Farm. Photo © Scott Hill

Pigeons a la Rouse

Side of the pigeon house with the pigeon door, at Rouse Hill. Photo Scott Hill © Sydney Living Museums

Just to the rear of Rouse Hill House a pigeon house was built against the wall of the ca.1860 wool-shed, probably by Edwin Stephen Rouse who also built a large fowl-house nearby for both decorative and table chickens. Edwin’s great-grandson John remembers “[his grandmother Bessie] used to call it the pigeon house even though we had fowls in here because Grandfather used to have pigeons there and many of the pigeons used to run wild down in the stables.” [1] It was later used for the chickens at night, making it far easier to find the eggs that were otherwise scattered through the garden. High on each side of the cote are the remains of the pigeon doors – arch-topped holes high off the ground (and away from the snakes!) and fitted with swinging flaps that allowed any late-returning pigeons in after dark, but not back out. (In this photo the center between two doors has fallen away). [2] We’re not sure if the pigeons were initially also used for meat or were simply a recreational passion. [3]

Pigeons a la Neapolitana (a la Maclurcan)

This recipe for stuffed pigeons by Mrs Maclurcan – a copy of which survives at Rouse Hill – is actually quite easy, think of it as a variation on stuffing used for chicken or quail. Squab, young pigeon, is found in specialty butchers, and occasionally even in large supermarkets these days. The recipe she provides was written for very ‘fresh’ pigeon indeed – likely fresh from the pigeon cote ‘out the back’. The squab you buy may not come with innards ready to be made into a pate, but you could substitute chicken livers from the butcher.

6 pigeons, black pepper, chopped parsley, 2 lbs. bread crumbs, 3 dozen oysters, salt, 2 tablesoonfuls butter, 1 egg.

Mode – Pluck and clean the pigeons, wash them in the vinegar and water; clean and wash the giblets; the liver and heart through a mincing machine, then mix them in the basin with the breadcrumbs, the parsley very finely chopped, a salt spoonful of black pepper and salt; mix all these together with the egg and half of the butter, then divide equally into six pieces, and add to each part six oysters; stuff each bird as full as possible with the forcemeat, and put into a baking dish, dust each with flour, place over them a buttered paper, and a bake half an hour.

We’d suggest baking at 180 degrees.

Recipes a la pigeon

For fashionable menus written at the turn of the century French was de rigeur. While ‘pigeon’ is self explanatory, ‘pigeonneaux’ are young pigeon – what we would call ‘squab’. In my copy of ‘Menus made easy – or how to order dinner and give the dishes their French names‘ (Nancy Lake, New York, 1903) there are these variations.

‘Pigeons a la Craupadine’ – breadcrumbed and broiled; served with a piquante sauce

‘… a l’Algerienne’ – are stewed and served with French plums [this suggests an origin as a tagine to me]

‘… a la Princesse’ are stuffed with foie gras and mushrooms, stewed, and served with Espagnole sauce

‘… auz petits pois’, or ‘a la St. Germain’ are stuffed and stewed with green peas.

‘… a la Nivernais’ they are served with mashed turnips. [yes I know, mashed turnip! Positively gourmet!]

Pigeon a la Macleay

And here we hit one of those snags in reading older manuscripts, and in relying on them being in grammatically correct, modern French: pate can mean ‘pie’. In William Sharp Macleay’s 1859 menu he lists ‘pate de pigeon‘. Both Jacqui and I actually read this as being a cold terrine (rather than a smooth pate, such as a liver-based pate), Jacqui noting that there’s a raised pie already in the first course so a pie in the second is less likely. ‘Menus made easy’ however lists Pate chaud de pigeons as “a hot pigeon pie”, and Pate de pigeon aux l’Anglaise – now without the chaux – as “a pigeon pie with collops of beef steak”. Quite possibly this means that the dish wasn’t a terrine encased in pastry but a pigeon pie after all. Even our resident – and very fluent – French speakers couldn’t definitively solve the riddle.

Penthouses a la Pigeon

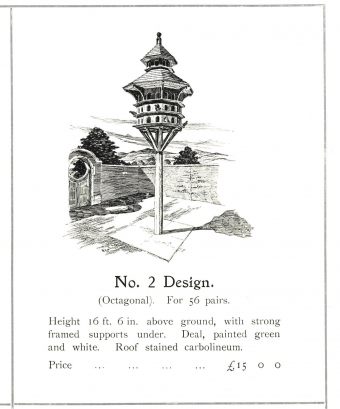

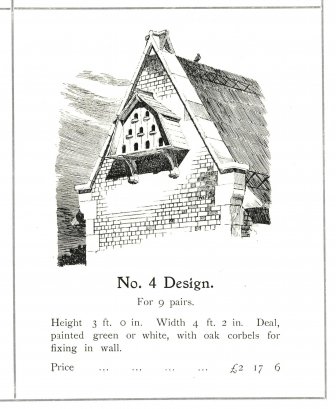

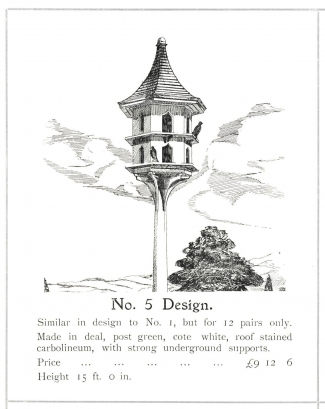

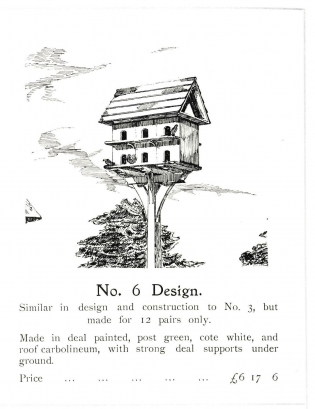

To finish, here are some pigeon houses so far removed from the farmyard ancestor you’d have to consider them pigeon apartments. They’re from The complete catalogue of garden furniture and garden ornament (London, John White, 1906). I suspect their residents were quite safe from a one-way trip to the kitchens:

Pigeon cote design no 2 in John P. White, Complete catalogue of garden furniture and ornament, The Pyghtle Works, Bedford, 1906. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TCQ 717 WHI

Pigeon cote design no4. in John P. White, Complete catalogue of garden furniture and ornament, The Pyghtle Works, Bedford, 1906. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TCQ 717 WHI

Pigeon cote design no 5 in John P. White, Complete catalogue of garden furniture and ornament, The Pyghtle Works, Bedford, 1906. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TCQ 717 WHI

Pigeon cote design no 6 in John P. White, Complete catalogue of garden furniture and ornament, The Pyghtle Works, Bedford, 1906. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TCQ 717 WHI

[1] Rouse Hill House oral histories: Dr John Terry. Tape 13, recorded 1st August, 1986.

[2] J C Loudon wrote: “The pigeon house or dovecote has been an appendage of the country house from the earliest ages; and nothing can be more simple or universally known that that its structure. The only essential requisite is, that it must be at some distance from the ground; because the pigeon is a bird that flies much higher than any of the domesticated fouls… The opening for the birds may be in the roof, or in the highest part of the side walls, with shelves before the holes for the birds to alight on; and the walls of the interior may be lined with boxes, divided into square holes for the birds to make their nests in; in short into pigeon-holes.

“(Encyclopaedia of cottage farm and villa architecture, 1846)

[3] Often mistaken for a pigeon cote – and today wired to prevent birds using it to enter the roof – the stables have a magnificent diamond-shaped ventilator incorporated into the brickwork at each end.