Through most of the nineteenth century, Rouse Hill House was the social hub of the district and the Rouse family regularly played host to formal society dinners, long luncheons and sociable tea parties, plus major family events to celebrate birthdays, weddings and Christmas.

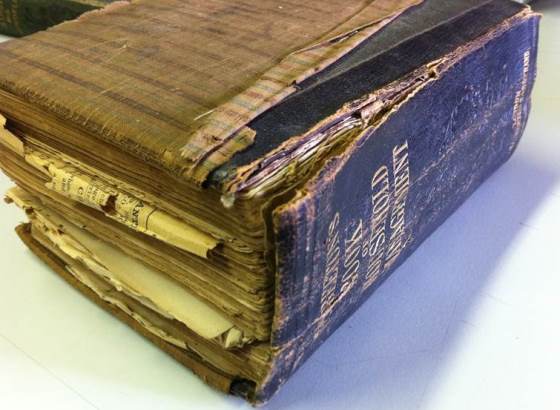

The family’s surviving cookery books, in various states of repair, date between the 1850s and the 1950s. While each is of interest in itself, as a collection they stand testament to the social and cultural changes that this family, and indeed, Sydney itself underwent in that 100 year period.

Members of the Rouse family and guests at the house by Major Thomas Wingate, 1859. State Library of NSW A 3804 PXA 780

Due to the nature and fragility of the house and its collection within, public access to the interior spaces is limited – especially to the kitchen. But through the family’s cookbooks’ tattered and splattered pages we have the ability to recreate some of their recipes in our own kitchens, giving us an intimate glimpse into lives past, literally giving us a taste of their history.

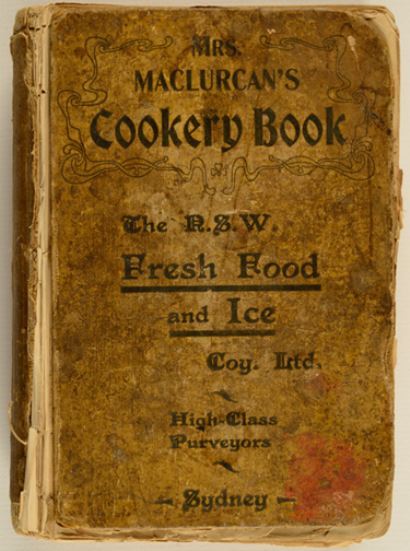

The books demonstrate the shift from a reliance on English cookery texts like Warne’s Model Cookery, Mrs Beeton’s and Alexis Soyer to locally authored – Australian Cookery for the people (1894) and Mrs Maclurcan’s cookery book (1903) which feature recipes with native and localised ingredients such as kangaroo tail soup, jugged wallaby, curried bananas, rosella jam and prickly pear jelly. You can take a peek inside some of these books and see some of their recipes here.

Mrs Maclurcan’s cookery book, c1903. Sydney Living Museums R89/70

Some of these books were in use for over 60 years– evident from 1950s newspaper page-markers in texts from that were published in the 1880s and 1890s. As a collection they illustrate generational change in terms of lifestyle, domestic organisation and relationships, a decline of wealth and the role of servants, and changing culinary technologies.

Hidden stories

They speak of many generations of Rouses: of Emma Rouse, whose godmother felt that she could learn the art of domestic management from Mrs Beeton, in 1863; of Bessie Rouse, matriarch of Rouse Hill house from the 1870s to the mid-1920s, her daughter Nina (who married George Terry of Box Hill, just next door) and of Kate Joyce, the Rouse’s long-standing cook. Kate Joyce ‘reigned supreme in the kitchen’ cooking for the family for over 30 years, only retiring when Bessie died in 1923. In fact prior to joining Bessie’s household in 1890, Kate Joyce had cooked for Bessie’s mother for almost twenty years, so she spent over 50 years of her lifetime cooking for Bessie’s family.

Manuscript recipes, secreted within the books, add to the strength and relevance of the collection, and bring a very personal element to it, reinforcing the social and familial connections that food provides through acts of sharing and exchange. Sharing or taking note of a recipe from a friend or distant family member acted as memento of times spent together, of shared tastes and experiences; handwriting just a small remnant of old friendships and family bonds.

Emma Rouse, c1855. Sydney Living Museums R86/513-4

The ‘beaten up Beeton’

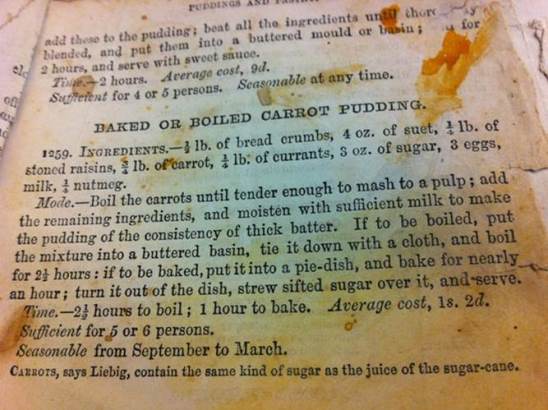

The very well worn book shown at the top of this post is a third edition, Beeton’s book of Household Management published in 1863. It was given to to Emma Rouse by her aunt in 1865, when Emma was 22. We call it ‘the beaten up Beeton’ due to its tattered state, but it would have taken pride of place on her bookcase when it was new. Emma left the colony in 1871 to join her husband in England, leaving the book behind. It’s battered state indicates that it was subsequently well used, whether by household staff or family members. Local newspaper snippets used as page markers date to 1909 suggesting that it was being used at least 40 years after publication – perhaps by Kate Joyce. My favourite page is the one with a carrot pudding recipe on it – with clear evidence of the recipe being tried at least once! I’ve made the baked version many a time, substituting butter for suet. It’s easy and quite delicious!

Mrs Beeton’s carrot pudding, Beeton’s book of household management, 1863. Photo Jacqui Newling © Sydney Living Museums

Carrot pudding

Ingredients

- 350g carrots (peeled and trimmed)

- 250g (4 cups) fresh breadcrumbs (made from 2-day-old white bread, crusts removed)

- 120g butter (or suet), diced

- 100g sultanas

- 100g currants

- 80g (1/3 cup) white granulated sugar

- 3 eggs (beaten)

- 1/4 teaspoon ground nutmeg or ground cinnamon

- milk (optional)

Note

Carrot puddings have been made for centuries in Britain and Europe. Be sure to use homemade breadcrumbs, as prepackaged alternatives will not give the required light texture. The carrot-coloured splotches on the recipe page in Emma Rouse's 1863 edition of The book of household management suggest it was a family favourite. It is delicious served warm with ice-cream, or cold as a light alternative to fruitcake.

Serves 8

Directions

| Grease a 23-cm pie dish. | |

| Boil or steam the carrots until very tender. Drain them and allow them to cool. Transfer them to a bowl and mash them to a pulp. | |

| Preheat the oven to 180ºC (160ºC fan-forced). | |

| Combine the mashed carrot with all the other ingredients and mix well. Ideally the mixture should be the consistency of thick batter, but add milk if it seems heavy and dry. Transfer the mixture to the pie dish and bake for 45–50 minutes, or until a skewer inserted in the centre of the pudding comes away clean. Allow to cool a little before serving. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe