Unappetising as it might seem today, tongue was regarded a delicacy in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Tongue was on the menu at formal dinners, sociable breakfasts and wedding banquets, and at the gala ball held at Government House for the Prince of Wales, Edward VIII (who later abdicated the throne to marry divorcee, Wallace Simpson) when he visited Sydney in 1920. If you look carefully on the image above, you will see the tongue sticking out behind the syllabub (the creamy substance piled high on the pedestal dish) on the Supper Table image from 1895.

Rich tastes

Tongue is a very rich meat, and like many types of offal, known to aggravate gout, a constant source of complaint for those afflicted with the condition. The prevalence of gout among wealthier colonists may partly be because boiled tongue was often, according to Mrs Beeton in 1861, served instead of ham ‘and is, by many persons, preferred.’

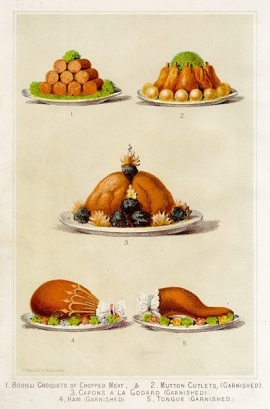

Colour plate showing ‘Tongue garnished’ (bottom right) in Mrs Beeton’s book of household management, 1895. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection © Sydney Living Museums

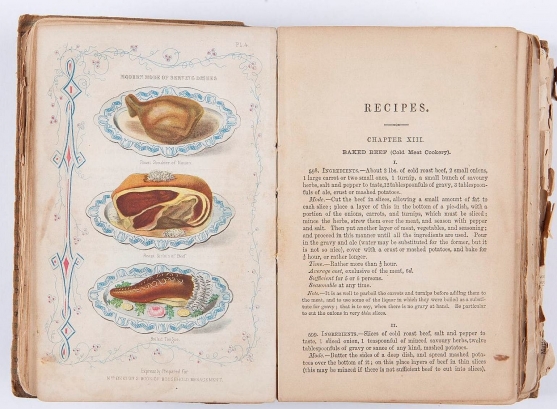

Ox tongue was the most prestigious, however sheep’s or lambs’ tongues were also popular, especially in Australia. Before being cooked, tongues are generally cured, pickled in a similar fashion to corned beef, and sometimes there were smoked. They are somewhat fiddly to prepare – which may contributed to their demise; even if purchased ready-pickled they need to be soaked for a few hours. Contemporary recipes invariably say ‘boiled’ however boiling renders the tongue-meat hard, whereas ideally it should be quite softly textured, with a smooth consistency. Poaching is a better method.

Grandma’s slippers

The tongue then has to be peeled, to remove its leathery external ‘skin’. This is relatively easy to do, just by running your thumb beneath the skin to release it from the flesh beneath. As the skin toughens as it cooks, the tongue’s shape distorts, to resemble a wedge-heeled shoe, prompting a family friend’s nickname for lambs’ tongues as ‘grandma’s slippers’.

Colour plate from Emma Rouse’s copy of Mrs Beeton’s book of household management, 1863. Rouse Hill House collection. © Sydney Living Museums

Tongue-tied

Once cooked, the tongue could be served whole, either hot or cold, to be carved at the table. Colour plates in period cookbooks invariably show tongue adorned with a paper ruffle to hide the rather unsightly ‘roots’. Mrs Beeton gives a graphic description of her method of taming a tongue:

‘If to serve cold, peel it, fasten it down to a piece of board by sticking a fork through the root, and another through the top, to straighten it. When cold, glaze it, and put a paper ruche [ruffle] round the root, and garnish with tufts of parsley.’

Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s book of household management, 1861

Beeton suggests tongue be garnished with ‘tufts of cauliflower and Brussels sprouts’, whereas William Sharp Macleay, who lived at Elizabeth Bay House in the mid-1800s, liked his served with ‘sauce piquante’ a rich gravy flavoured with pepper, cayenne (chilli) and red wine vinegar. Leftover tongue could be potted as a breakfast or supper dish, or ‘hashed’ and made into croquettes or similar. Alternatively, tongue could be packed into a loaf tin or decorative mould with the poaching liquid added and left to cool. Once cold, the poaching liquid sets into an aspic or jelly, and the tongue was sliced, brawn style.

Languishing in popularity

Tongue lost its place on Australian tables after the Second World War. It had little export value, and, like other offal and organ meats, was not rationed. Once the War was over, prime cuts that had been hard to get during the war years became the heroes, and this once highly fashionable food found itself languishing in popularity. That they are time consuming to prepare probably added to their demise. Today you are most likely to find fresh tongues being sold in Asian-style butchers’ shops, and some traditional ‘old school’ butchers will cure them to order. Pressed or jellied tongue can be still found in delicatessens, locally produced by continental butchers, or in tins imported from Europe and Britain, where they have stood the test of time. Adventurous chefs are making attempts to revive tongue on modern menus, but most admit that the market is still very limited – people finding the texture disagreeable, or the concept of eating something that once resided in an animals mouth disagreeable.

Sliced veal tongue. Photo © Jacqui Newling for Sydney Living Museums