A hive of industry, and busy as a bee – the work of the humble ‘bumble’ and ‘honey’ bee is extraordinary – their efforts providing honey and bees wax, highly coveted for candles in our colonial past. But more importantly, bees are integral to agriculture, and it was quickly recognised that in order for introduced crops to thrive in Australia, European bees were needed to pollination.

Join us in this video, made for Sydney Living Museum’s Spring Harvest Festival, where you can join us in the kitchen garden for a guided honey tasting with Doug Purdie from The Urban Beehive, who looks after the bee hives on the Vaucluse House Estate.

Noble intentions

Bees are often used symbolically (especially by the French) as is the domed skep (shown at the top of this page, and below) which acts as an inherent symbol for them, to represent ‘industry’ and productivity, a notion that directly relates to their association with agriculture and harvests. The first official government seal for the colonies of New South Wales depicted a traditional woven bee skep, which you can just make out in this wax impression from 1792 (below), to the left of ‘Industry’, seated on her bale of goods (below).

The original seal was described when it arrived in the colony:

On the obverse were the king’s arms, with the royal titles in the margin; on the reverse, a representation of convicts landing at Botany Bay, received by Industry, who, surrounded by her attributes, a bale of merchandise, a beehive, a pickaxe, and a shovel, is releasing them from their fetters, and pointing to oxen ploughing and a town rising on the summit of a hill, with a fort for its protection. The masts of a ship are seen in the bay. In the margin are the words Sigillum. Nov. Camb. Aust.; and for a motto “Sic fortis Etruria crevit.” The seal was of silver; its weight forty-six ounces, and the devices were very well executed.

David Collins 1792.

‘A hardy and thrifty set’

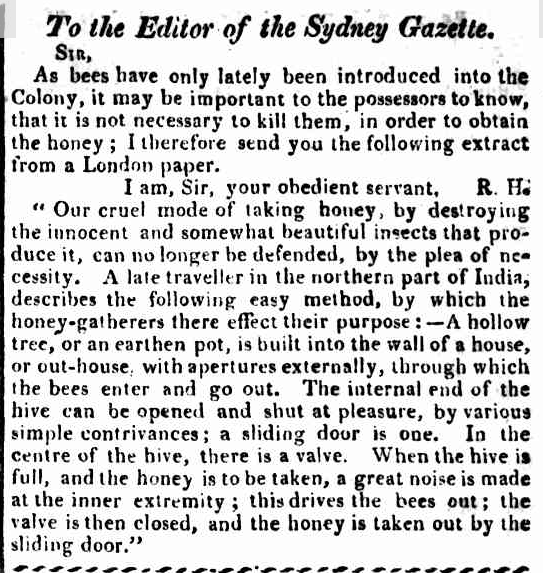

When you think that bees had to spend four months sea-voyaging across the equator, it is little wonder that the few that arrived on our shores found difficulties surviving in the settlers’ gardens. Some success was found in 1822,when ‘seven hives of bees – recently arrived from England’ were put up for auction by Simeon Lord [2]. Four of these were purchased by Mr Parr, of George Street, Sydney, and according to the Sydney Gazette and Advertiser, their inhabitants were ‘a hardy and thrifty set.’ The article paints a picture of delight as these new creatures adventured in their now locale:

As soon as the dawn appears, the little animals issue forth from the rest they have enjoyed during the night, and commence their aerial journey over their newly-acquired land; and one squadron no sooner returns heavily laden with spoil, than another troop may be viewed winging away for some favored spot that seems perfectly congenial to their prosperity and nature.

Sydney Gazette and Advertiser, Friday April 12, 1822. p.2

A sweet sensation

In 2016, Doug Purdie from the Urban Beehive installed hives in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House, and the honey harvested from the hives is sold at the gift shop at the museum or online. For our Spring Harvest Festival we filmed Doug in the kitchen garden, to take us through a guided honey tasting.

Lost romance

Much of the romance of bees seems to be lost (but none of their mystique – what does go on inside their hives?) with the advent of the more practical layered wooden box-hives in general use today, but the classic dome shape of the traditional skeps is retained in decorative honey pots, tea cosies and bee-hive ‘hair-dos’! Just like all the sugar loaf mountains, the historical nomenclature outlasts the actual namesake.

A sweet tooth

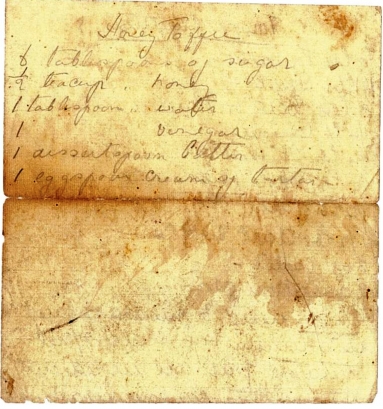

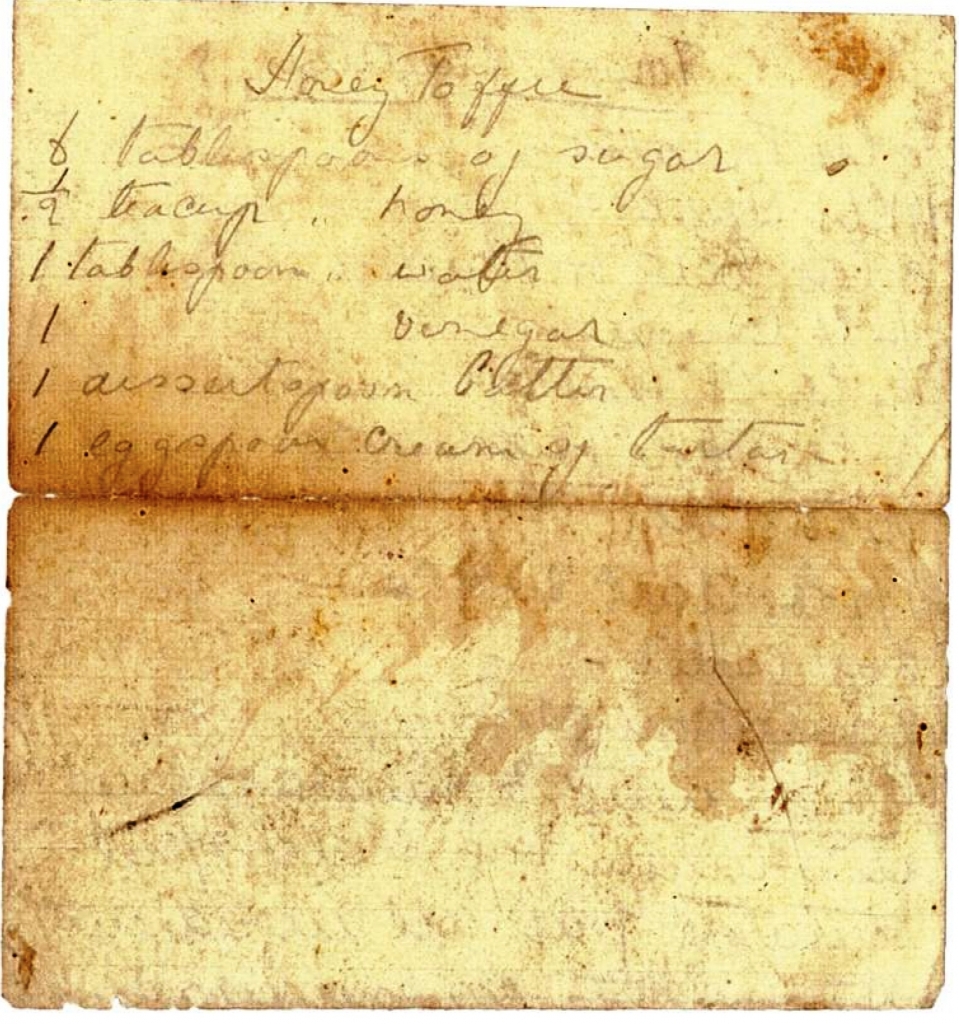

This Honey Toffee recipe, which is similar to a caramel or butterscotch lolly, was found inside a small children’s book that belonged to Kathleen Rouse of Rouse Hill House. Since it had no instructions for actually making the toffee, I’ve had to consult other recipes to come up with a workable method. It’s defining feature is the honey, having more character and piquancy than a sugar-based alternative.

Honey toffee

Ingredients

- 200ml honey

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 2 tablespoons water

- 2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

- 20g butter

- 1 teaspoon cream of tartar

- 15 mini silicone lined patty pans or baking paper

Note

This recipe, written on a slip of paper with youthful handwriting, was secreted inside a children's book belonging to Kathleen Rouse in the late 1800s Good things made, said and done for every home & household c 1885. It is a ‘butter toffee’ much like caramel or butterscotch. Like many manuscript recipes, no method is given, so I was guided by similar recipes to come up with a workable method. I have doubled the original quantities so there is more to share.

Directions

| Combine the honey, sugar, water and vinegar in a deep-sided saucepan and heat gently, swirling the pot now and then - do not stir it with a spoon - until the sugar has dissolved. Increase the heat, bringing the mixture to the boil, then let the mixture boil until it reaches 145° Celsius or 'soft-ball stage' (explained below). This may take 5–10 minutes, and be very careful – the mixture will bubble up in the pot. | |

| Once the required heat is reached, remove the pot from the heat immediately, add butter and cream of tartar, gently stirring with a metal spoon until fully incorporated. | |

| For individual toffees, spoon a tablespoon or so of the mixture into mini silicone-lined patty pans and refrigerate until set. Alternatively, pour the mixture into onto a baking sheet and refrigerate until it sets. Break the toffee into large pieces. Store the toffees in the fridge - they will soften and be difficult to manage if not kept cold. | |

| COOKS TIP: A candy thermometer will be useful for making this toffee, to determine when the required 145°C is reached. Otherwise, you can test whether the toffee has reached ‘soft ball’ stage by dropping a small amount into a glass of cold water, and pressing it gently to see that it holds a ball shape. | |

This post has been adapted from ‘All a-buzz in the kitchen garden’ published in October 2016.

Sources and further reading:

[1] Barrett, Peter. The immigrant bees 1788 to 1898 : a cyclopaedia on the introduction of European honeybees into Australia and New Zealand. 1995

[2] Sydney Gazette and Advertiser March 15, 1822 p.2

[3] Sydney Gazette and Advertiser 12 April 1822 p.2

[4] Collins, David (1756-1810). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]. 1798.

Print recipe

Print recipe