So blow me down ye son of a biscuit eater! Here be a tale of pirates at that den of infamy, Parramatta! – and a curious recipe for ‘Pirate’s delight‘! Arrrr!

You may remember Thomas Mitchell’s description of the Macarthurs’ gardens at Elizabeth Farm, and the enigmatic reference to ‘Greek pirates’ working the vine:

I observed convict Greek pirates— “acti fatis”—at work in that garden of the antipodes, training the vines to trellices, made after the fashion of those in the Peloponnesus.

Hang on – ‘Greek pirates’? In Parramatta?? Shiver me timbers!

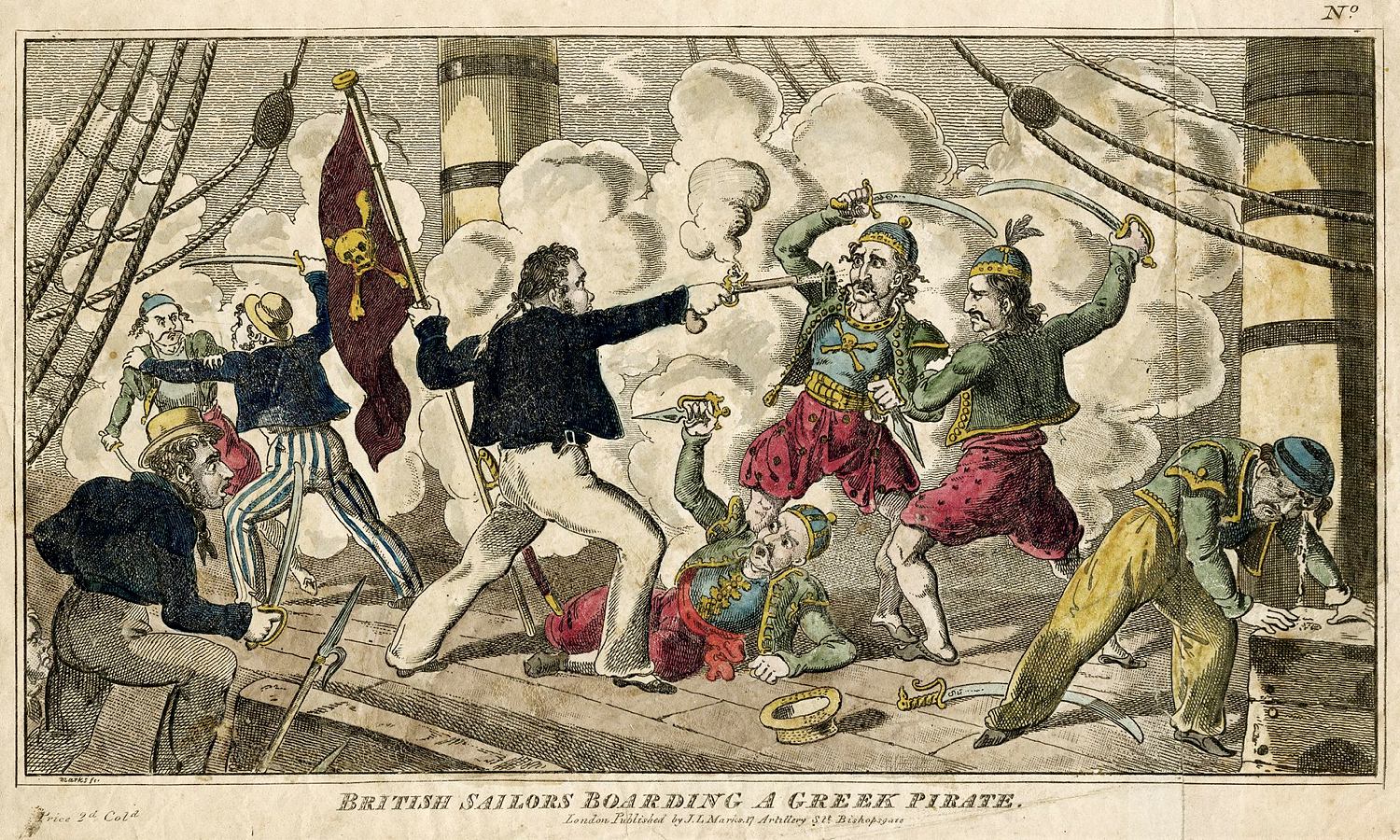

Drama on the high seas!

The Mediterranean in the 1820s was an unpredictable, often unsafe place: the Barbary Pirates – the infamous Corsairs – were still active along the African coast, and to the east the Greek war of Independence against the Ottomans made the Aegean hazardous. The British navy patrolled the waters, providing escorts to their and their allies’ merchant ships. Even the New South Wales’ colonial press reported on the numbers of Greek ships that had turned to ‘piracy’. Expressed in terms of 19th century literature it was all very picturesque and romantic – albeit deadly and with little chance of humming the tunes on the way out after the curtain call. Just as today, with pirates off the coast of Somalia an ever present danger to shipping, the danger of international piracy was an issue to the colony. Governor Arthur Philip was empowered by George III to act with the powers of a Vice Admiralty Court in trying “acts of piracy in waters adjoining the territory of New South Wales.”

One such ship was seized by the British off the Libyan coast. Amongst the prisoners were 7 described evocatively as ‘Greek Pirates’. Jane Kelso, Sydney Living Museum’s historian, has looked into their fate and that of one ‘pirate’ in particular: “Mariner Androni Tu Malonis, a native of the Isle of Hydra, just off the North-east coast of the Peloponnese. Malonis was tried with nine of his countrymen in Malta in February 1828 for an act of piracy committed the previous year. Seven were found guilty and sentenced to death, four with a recommendation for mercy. Eventually all sentences were commuted to transportation, with Manolis – also spelled Malonis – one of three sentenced to life.”

“In August 1829 these Greek pirates arrived from England aboard the Norfolk. Andonis Manolis was 22, single, literate and Protestant. He was described as 5ft 4¾, with dark brown hair and eyes, a dark ruddy complexion and a perpendicular scar on his nose. It was also noted that the pupil of his left eye was small, with a scar at the corner. He was assigned to William Macarthur [the youngest son of John and Elizabeth Macarthur] at Camden, and was presumably one of the ‘convict Greeks’ Thomas Mitchell observed working on the vines in the Elizabeth Farm garden in November 1831.”

But what had they actually done to be apprehended and sentenced for ‘piracy’? They had been on a vessel that stopped the Alceste, a British-owned Maltese ship which was en route to Alexandria and ‘replenished’ their own supplies from its cargo. This wasn’t a straightforward case of skullduggery, pillaging and colourful language; they claimed at their trial that they weren’t actual pirates but part of the Greek independence cause, which justified their raiding a ship bound for an Ottoman (and hence enemy) controlled port. And why Malta? The island of Malta was actually a British colony, having been declared a Protectorate in 1800, before being upgraded to full colonial status in 1814.

Stow-away!

One of the Elizabeth Farm Greeks, either Malonis or his compatriot Nicholas Papendross who had also been assigned to William Macarthur, may have tried to escape the colony. The Gazette reported:

One of the Greek pirates who were transported to this Colony some time back for their atrocities in the Archipelago, was found stowed away on board the brig Wellington when getting under-weigh, and handed over by Mr. Oliver to the constables. He is in the service of Mr. M’Arthur, and on being called upon to account for his attempt at escape, said he went on board to see a friend, with whom he was taking a glass of grog and a cigar, when the ship began to move, and was taking him away against his will.

6 years later however their lives changed dramatically. The new Greek government had petitioned its British counterpart for their release, and it was agreed that all would receive an absolute pardon and be provided with free passage back to England. Colonial secretary Edward Deas Thomspon wrote to the Principal Superintendent of Convicts:

‘With reference to my letter of the December [sic] respecting the Convict Greeks named in the Margin [named as Andrini Tu Manolis, Damianos Ninas, Jorghis Vassilachis, Ghicas Bulgaris, Jorghis Larrenzou, Nicholas Paperndross and Costandis Strombolis] being furnished with a free passage to England as authorised by His Majesty’s Government I do myself the honor to inform you that such of these men as prefer to receive a Gratuity of Twelve pounds to purchase Clothes in lieu of a free passage as before offered will be permitted to do so; and to request that you will enquire and report as early as possible the indulgence as above mentioned which each prefers. The money will be placed in the hands of the Ships with whom being all Sailors they engage.’ (25 February 1837 )

In other words some had found employment as paid sailors for the trip back. Two however elected to stay: Manolis and Ghikas Boulgaris – who had been assigned to another landowner with a strong interest in viticulture, the one-time Colonial Secretary, Alexander Macleay. We can safely assume that, apart from picking their brains as to Greek techniques of training grape vines on trellises, the horticulturally-minded Macarthurs and Macleays also found out all they could from the two about the production of that other Greek icon – the olive. Grapes and olives had formed part of Macarthur’s plea to be allowed to return to the colony after his long post-Bligh exile. Writing to Earl Bathurst, secretary of state for the colonies, he called them “[t]hose two great sources of human enjoyment and wealth” [1 August 1816] . Bathurst then stressed to his under-secretary Henry Goulburn (are you recognising some NSW town names here?) that Macarthur had been collecting vine and olive tree specimens in France and Switzerland ready to take them to the colony, where they would undoubtedly prove most beneficial.

Jane continues with Manolis’ story: “In February 1854 a certificate of naturalization was issued [by Governor Charles Fitzroy] in the name of ‘Antoni Manlis’, said to be the first naturalised Australian Greek. Described as a 47 year old sailor and labourer, native to Athens, Greece, and now residing in Upper Picton [South-west of Sydney], the certificate was issued for a common reason – so that Manolis could obtain legal title to land he had purchased. Manolis remained in the Picton area, where he died in 1880 and was buried in a local Anglican cemetery.”

Pirates Delight!

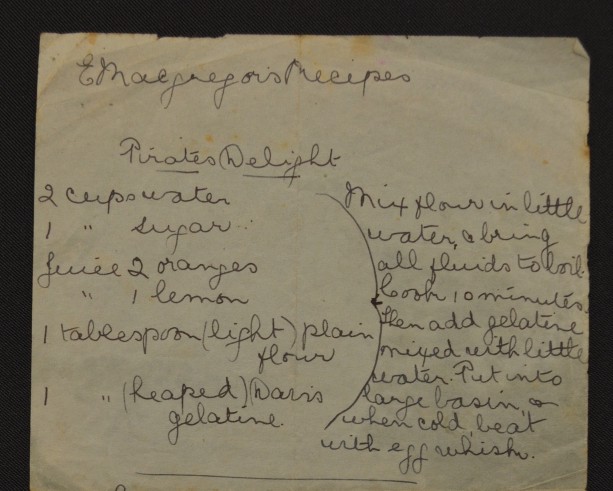

So in memory of the ‘Greek Pirates’ here’s a recipe for Talk Like a Pirate Day, a little treat found tucked away in the Meroogal manuscripts and likely from Elgin Macgregor’s kitchen repertoire: ‘Pirates delight’. In appearance and texture it’s very similar to lemon curd – completely different to any jelly you’d have had before. Before they owned a refrigerator the Meroogal ladies lowered their jellies into the cold cistern just outside their back door to help them set – a common 19th century practice. The citrus juice is obviously to prevent scurvy while raiding the Caribbean, or that other den of piratical infamy the Shoalhaven! Enjoy with a bumper of rum and eat to the tune of “A rollicking band of pirates we” from The Pirates of Penzance. Yo ho ho!

Pirates delight manuscript recipe, E Macgregor. June Wallace Papers, Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Pirates delight

Ingredients

- juice of 2 oranges

- juice of 1 lemon

- pulp from 6 passionfruit, optional

- 1 cup sugar

- 3 teaspoons plain flour, sifted

- 1 heaped tablespoon unflavoured powdered gelatine

Note

This rather curious recipe was found amongst papers relating to Meroogal, a historic home at Nowra, south of Sydney. It's name must come, we think, from its citrus flavour, but we've found another recipe for it that includes passionfruit, so add them too, if you like. It's quite delicious, tasting rather like a light or 'mock' version of lemon butter or curd - perfect for dieters!

Directions

Place juice into a saucepan, add sugar, and two cups of water. Stir on a gentle heat until sugar dissolves.

Mix the flour into two tablespoons of water and blend until smooth. Add to the juice and bring gently to the boil. Reduce heat to a simmer and cook for ten minutes.Pour 2 tablespoons warm water into a small bowl, add a little of the hot juice, add gelatine and stir to dissolve. Pour the dissolved mixture back into the pot and mix until completely incorporated.

Pour into a large bowl and allow to set in the fridge. Once set, beat with an egg whisk, to lighten the texture and add volume.Enjoy over ice-cream or dolloped onto chilled custard, or as a tangy layer in a trifle (not so dieter friendly after all!)

Makes about three cups.

A fruitier variant of this recipe comes from the Northern Star newspaper:

PIRATE’S DELIGHT

Ingredients—2 large cups of water, 1 large cup of sugar, juice of 2 oranges and 1 lemon, 6 passion fruit, 1 heaped tablespoon of flour, 1 heaped tablespoon of gelatine.

Method.—Soak gelatine in a little cold water and stir till dissolved, Boil water, sugar, flour, orange and lemon juice together for 10 minutes, add gelatin. When cool whisk for 20 minutes- then add [fold in] juice and pulp of 6 passion fruit. Serve with cream or custard.Northern Star (Lismore), Wednesday 8 August 1928

Mathew Stephens from the Caroline Simpson Library did point out that ‘Piracy’ isn’t a collection strength per-se, but still found this gem to end on:

Captain Kidd and his victim’ in Professor Hoffmann, Drawing-room amusements and evening party entertainments, George Routledge & Sons, London, 1883. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

Arr landlubbers! Got a taste for more?

At the Hyde Park Barracks Museum you can search the convict database, as well as learning all about convict life in Sydney. Manolis features in the new Barracks interactive Lags & swells on level 3 of the museum. The spelling of the names of the piratical ‘Hydra 7’ vary from document to document. In the database they are given as Androni Tu Malonis, Ghicas Bulgaris, Jorghis Larizzos, Jorghis Vassilachis, Damianos Ninis, Nicholas Papendros and Costandis Strombolis.

The Dictionary of Sydney has an entry on the Greek community in Sydney including the ‘Pirates’. See http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/greeks

Jan Ross, Antonios Manolis: the first Greek and Athenian born settler in New South Wales, published by the Picton and District Historical & Family History Society Inc, Picton, NSW, 1991.

Print recipe

Print recipe