The houses in Susannah Place were designed with basement kitchens, with access to the rest of the house via a frighteningly steep and narrow external staircase. Each kitchen had an open fireplace which before long was fitted with a fuel cooking stove that would warm the living spaces above in winter, but add to the heat and discomfort in summer. Unsurprisingly, as technology allowed, the basement kitchens were abandoned in favour of internal kitchens on the same level as living areas. No. 58 was the exception, and its basement kitchen was in use from 1844 to 1974.

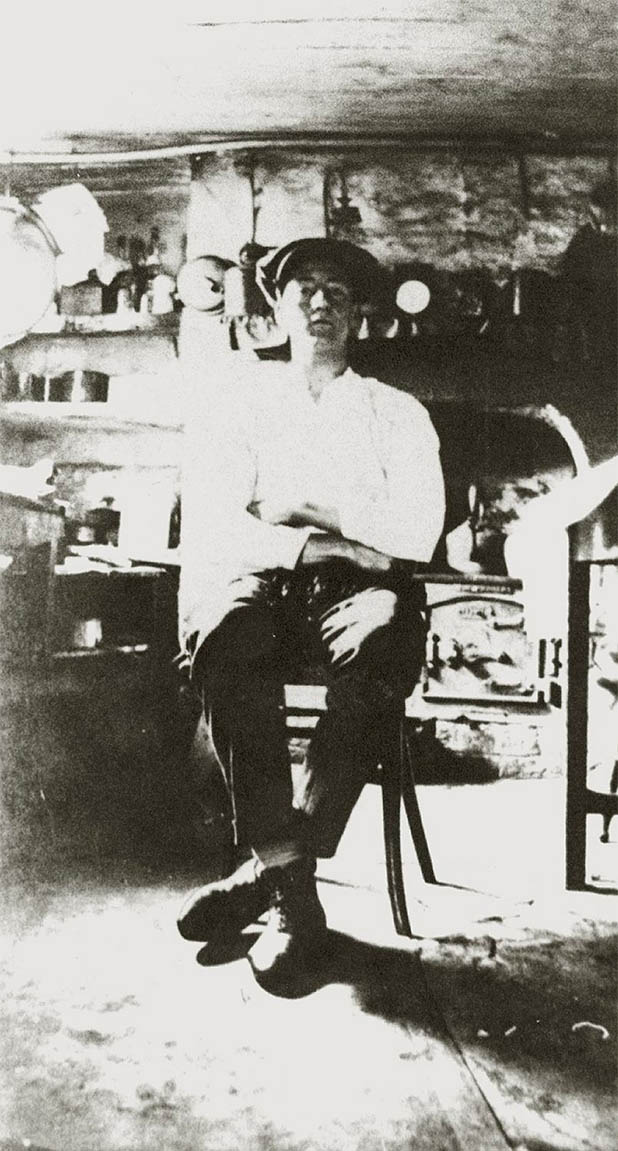

Fred Hughes in 58 Gloucester Street basement kitchen, c1920s. Courtesy Cleo Grayson and Karen Moffatt

Fred Hughes, pictured above, lived at #58 in the 1920s. The photograph captures the everyday details of the Hughes’ family kitchen: iron fuel stove, pots & pans, makeshift shelving. Fred provided an oral history record in 1994, explaining that the family would ‘live’ in the kitchen in the wintertime, taking advantage of the warmth from the fuel stove. They’d play cards around the kitchen table, with the aid of a kerosene lamp hanging on the wall. The kettle was always on the stove, and washing up was done in a dish – there was no sink or running water when he lived there. Fred’s memories evoke the scene and smells of in the kitchen at #58:

We had a lot of fish soup. Father would bring home fish he used to catch. There was always fish simmering in a pot on the stove.

The Hughes family vacated Susannah Place in 1931 for a better appointed house nearby, which had electricity, and understandably, according to Fred, the family ‘felt like kings!’

Girlie’s kitchen

Girlie Andersen had a long association with Susannah Place. Her parents had lived in number 58 since 1934, and Girlie and her husband Martin Andersen moved into number 64 (the shop was no longer operating) in 1937 to be closer to them. Number 64 had an upstairs kitchen and extra space with its balcony extension, which must have been a boon for a family with two young children, Ernie and Jack. But in 1949 when Girlie’s parents died, the Andersen’s took advantage of cheaper rent, and moved into 58, which then became home to various members of the extended family until 1974.

Although cooking ‘below stairs’, Girlie had the benefit of an electric light to work under, as the image above, taken in the 1950s, shows. The fuel stove from the Hughes’ time gave way to a gas cooker at some point, and although the cooker itself has gone, splatters and splodges on the walls and a changes in the paintwork create a silhouette of where it once stood!

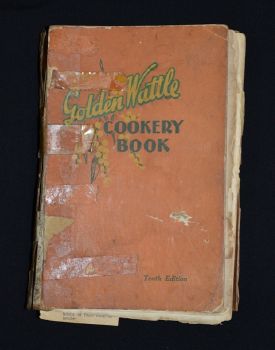

The Golden Wattle Cookery Book used by the Andersen family. Gift of Terri Williams, Historic Houses Trust

Girlie’s ‘go to’ text was a 1948 edition of the Golden Wattle Cookery Book, and it stayed in the house with Ernie who consulted it long after his mother had died. Its well thumbed pages give clues to the family’s favourite dishes, and cut-outs from newspapers and typed up snippets on pink paper slipped between the pages indicate that food and cookery was a constant interest. Testament to the popularity of curry powder as the home-cook’s secret weapon for adding pizzazz to a meal, the Kedgeree and Curry and Rice pages are shamelessly stained. A newspaper clipping of a Rabbit curry is similarly marked with tell-tale staining, and is a reminder of the leaner times when the ‘Rabbitoh’, or rabbit vendor, plied the streets with his catch to sell to local householders. Similarly, the fish croquettes page looks well visited, and a cluster of fish recipes slipped into the fish section of the book suggest that locally caught fish, the product of leisurely pursuits or necessity, might have been put to good use. Kangaroo tail soup and a Kangaroo steamer recipe suggest other frugal options for lower budget households.

Lemon fluff (basically a lemon delicious), was seemingly consulted, as was lemon tart (lemon meringue pie), with certain steps underlined with blue pen, and instructions for pastry making obviously followed carefully. Unlike many other family cook books I’ve studied, the savoury pages look more heavily used than sweet, and less than half the additional gleaned recipes were for cakes and desserts, the majority for boiled puddings and tarts. Perhaps the Andersen’s didn’t have sweet-tooth tastes, or perhaps there was too much to be done in a day to spend time on baked treats. Or with two sons, practical hearty fare took priority over dainties, and it was simply easier to buy biscuits or for a sugar hit, or bread and jam. We can only conjecture.

A number of sago recipes caught my eye in Girlie’s Golden Wattle Cookery Book. I’ve loved sago puddings as a summer treat since first trying gula melaca in Singapore many years ago but it’s an almost forgotten ingredient in modern Australian kitchens. Sago, or tapioca, was a popular standby well into the mid-twentieth century, so much so that old kitchen canister sets would often include one for sago. It was undoubtedly used readily in Susannah Place kitchens, as a regular stock item in #64’s corner shop records; it was inexpensive and a little bit goes a long way.

Sago snow

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup sago or seed tapioca

- 3 tablespoons sugar

- 2 lemons (rind of one, juice of 2)

- 2 egg whites (keep yolks for another use)

Note

Light, white and fluffy, 'snows' were popular even in the 16th century. They seem to have fallen from grace with the advent of the domestic freezer, when ice-cream became the ubiquitous summer treat.

This recipe is inspired by a recipe from Girlie Andersen's Golden wattle cookery book, published in 1948. Traditionally, custard would be made with the leftover egg yolks to make a complete dessert.

Directions

The Golden Wattle Cookery Book, compiled by Margaret A. Wylie, was first published in 1926 and can still be purchased today, in a metric 1993 version.

Print recipe

Print recipe