In keeping with British tradition, plum pudding was once ubiquitous for any celebratory occasion – not just Christmas. At the feast that was held to mark the opening of Hyde Park Barracks in 1819, Governor Macquarie served roast beef and plum pudding to 600 convicts.

Nineteenth century cookbooks abound with recipes for the many puddings that were a peculiarly British staple enjoyed across all classes. These were sweet or savoury batter puddings and suet puddings, made with oatmeal, dried peas, bread, rice, semolina – and sometimes enriched with eggs, spices and fruit; all of which were baked, steamed or boiled. Seemingly humble in origin, they were often named in honour or their creators, or famous devotees – such as Cabinet, Queen’s, Nesselrode’s or Herodotus’ pudding – and ranged from simple to highly complex concoctions.

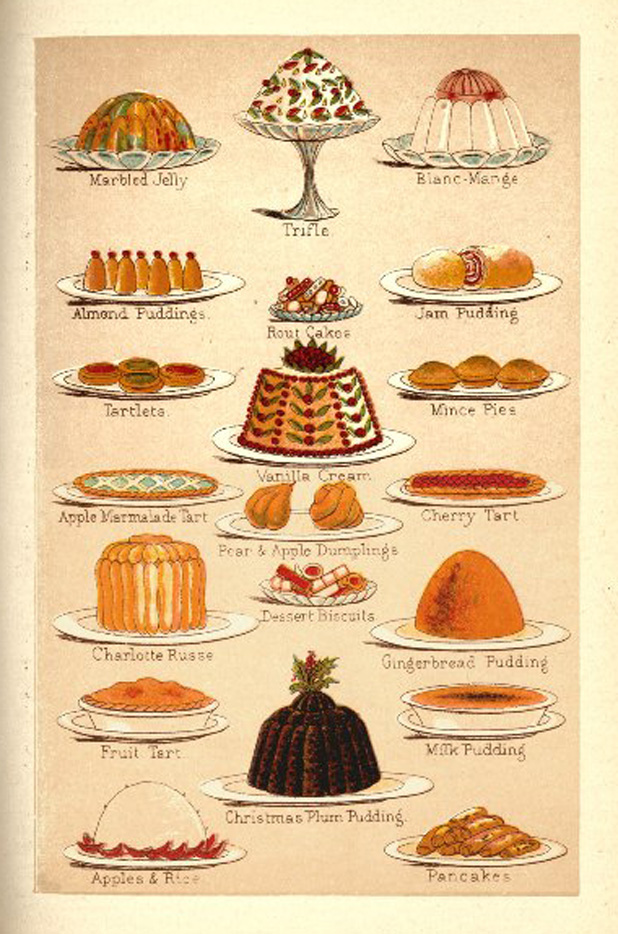

Colour plate in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s every-day cookery and housekeeping book, Ward, Lock & Co, London, 1895. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Historic Houses Trust

It’s generally thought that the word ‘pudding’ stems from boudin, the French word for sausage. Traditionally a pudding was made with any manner of meat, offal, cereals and seasoning, encased and cooked in an animal intestine or membrane. As well as the humble sausage, haggis and black or blood puddings are reminders of this once common practice.

The trouble with making puddings in natural skins was that the intestines or stomach linings were difficult to use, requiring a rigorous cleansing process, and were awkward to fill (but I still think real skin is what distinguishes a good quality sausage from an ordinary one). Plus you needed access to freshly slaughtered animals, which was not always possible.

A very democratic dish

The method of boiling the pudding mixture in a cloth was a revelation, and puddings came into general use across all classes from the 17th century onwards [1]. Even poor folk could afford a piece of cloth that, properly cleaned, could be reused repeatedly. The other benefit of a boiled pudding over bread and cakes was that not everybody had an oven to bake in. Only large or wealthier homes had baking ovens, but almost everyone would have had a boiling cauldron hanging in the domestic fireplace. Affording fuel was the difficulty in very poor areas, but there were often communal cooking fires with large cauldrons available for public use. This was certainly the case in the early Sydney settlement.

Remnants from these traditions are the now all-but-forgotten Aberdeen sausage, which still appears in Margaret Fulton’s Encyclopedia of Food & Cookery today with instructions to cook it in a calico cloth, and French style galantines (now cooked wrapped in cling film or cryovac parcels).

Celebration food

Dried fruit – currants especially – were used to sweeten breads and puddings before sugar became affordable. The English still have their ‘Spotted Dick’ and raisin toast shares similar origins. For the poorer classes, fruit-rich breads, cakes and plum puddings (plum was a general term for dried fruit) were reserved for special occasions; for example, Easter buns, wedding or ‘Bride’ cakes and the Christmas pudding.

As a winter festival food, the plum pudding was ideal; fresh fruit was limited but dried fruit stored well, bread was always at hand, and eggs might be the only challenge if hens weren’t laying. The use of alcohol and spices and the quantity and variety of fruit meant that the ‘rich’ plum pudding was deemed a special occasion food.

To cloth or not to cloth?

Eliza Acton (1845) advocated cloth bound puddings. According to her, batter puddings were:

much lighter when boiled in a cloth, and allowed full room to swell, [than] when confined to a mould. Plum-puddings, which it is customary to boil in moulds, are both lighter and less dry, when closely tied in stout cloths well buttered and floured. Cookery for Modern Families, 1845.

I have to admit that I’ve had little joy cooking plum puddings – homemade or purchased – in a cloth. They’ve either had an unsavoury floury paste adhering to the pud or, worse, to parts of it. Another reason for choosing a basin or mould over a cloth is that the cloths have an unpleasant odour, as Charles Dickens himself noted when his character Mr Cratchit describes his Christmas pudding experience in A Christmas Carol (see my ‘In December…’ post for the full quote). I’ve been offered lots of tips about the temperature and quantity of the cooking water, how much or little flour is required to line the cloth but I’m sorry, Eliza, I’ve sold out to the pudding basin!

‘A cannonball’

Today we may use silicone paper and tin foil, or heat-proof plastics, to save our puddings from drowning but the enduring Christmas pudding shape is, as Dickens described it, ‘a cannonball’. Decorative moulds like the ones illustrated above proved to be a Victorian fad. More modern alternatives – the ultimate being the tin can (how many of us grew up having puddings with the tell-tale ring marks from a tin can embedded into them?) – mean the fancy dessert mould has lost its place on twenty-first century tables. In true egalitarian style and with a yearning for tradition and authenticity, either the naturally spherical or basin shape has remained the universal Christmas pudding form.

[1] Kate Colquhoun Taste. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008.