While we all ‘holiday at home’ this April, why not try baking your own hot cross buns?

Who can resist diving into that (Easter) rabbit hole that is Trove! We just love that priceless archive of Australian newspapers provided by the National Library (NLA) – and have been having a look at celebrated food traditions at discussed in Easter-time articles. All make the point that these traditions have transcended time and cultures, most of them pre-Christian and even pagan or heathen in origin – and that many have invented ‘questionable’ attributions. They include Simnel cakes, and Tansy cakes – which are a kind of spinach pie made with bitter greens bound with eggs and ground almonds, and with honey added to neutralise the bitter flavour. Both are now obscure in the Easter repertoire and many will never have heard of them at all.

More enduring are Easter eggs – which were, until relatively recently, real eggs, hard boiled and decorated which children would play with, rolling them in ‘boules’-style competitions with their friends, and of course Hot Cross buns.

Old traditions & modern tastes

Tastes and food fashions change. In 1902 the Queensland Figaro lamented “The buns of the present day are not like the buns of our youth. They lack the spice, the crispness, and everything else to which our tender palates were accustomed” [Wednesday, March 26th, 1902]. Three decades later the Queensland Times reported that the traditional Easter bun was “not now quite so popular as it was even a decade ago“. That seems almost impossible to believe now, when packs of buns appear on supermarket shelves on Boxing Day (to outraged protestations) or in bakeries that run them all through the year in place of the conventional, plainly finished fruit bun.

Though the same newspaper claimed ‘Enshrined by traditions like a gem in a finely-wrought setting … [throughout] the changing ages Easter has never allowed itself to become “modernised“‘ [Queensland Times, Sunday April 11, 1936], we can hardly make the claim nearly a century later. Not only have chocolate eggs become the norm – themselves a late 19th century innovation – but Hot Cross buns are now available studded with chocolate rather than dried fruit, and there are totally fruitless versions, being merely a sugar-and-spice bun, marked with a flour-paste cross on top… tradition has well and truly fallen by the wayside.

If at first you don’t succeed …

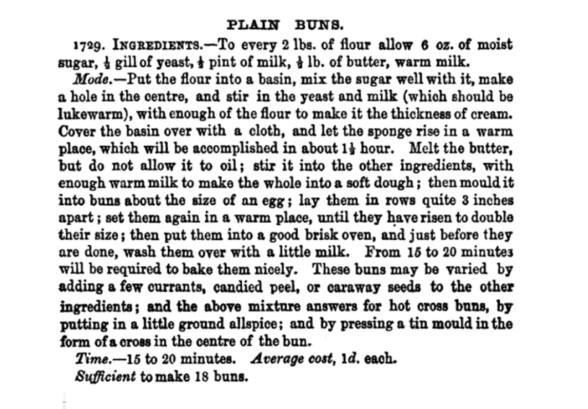

As a family we’re often away at Easter so I buy a few packs of buns – but 2020 is the year we’ll remember as the one when we all stayed home. A few years ago I gave a recipe a try for curiosity’s sake, and as we all ‘holiday at home’ this April I’m doing the same. Back in 2016 I was unable to find a mention of them by my favourite C19th century cooking writers – Maria Rundell and Eliza Acton – so I turned to Mrs Beeton’s ‘Book of household management’ (the trusty 1861 first edn.). While Beeton didn’t have a dedicated recipe for them, a footnote to her ‘Plain Buns’ recipe explains that with currants and candied peel added to the ingredients list, ‘the mixture answers for hot cross buns, by putting in a little ground allspice; and by pressing a tin mould in the form of a cross in the centre of each bun.’

The addition of spice is important, harking back to times when spices were an expensive, imported luxury in Britain and Europe, for many reserved for special occasions, and as what distinguished a ‘plain’ cake or pudding from a ‘rich’ one. Mrs Beeton had a definite leaning towards allspice but the more traditional English-style ‘mixed spice’ is the accepted fruit bun flavour we recognise today.

It is an inexpensive spice, and is considered more mild and innocent than most other spices; consequently, it is much used for domestic purposes, combining a very agreeable variety of flavours.

Mrs Beeton on ‘allspice’ in 1861.

Sugar & Allspice

Despite its name, allspice has a single source – the dried berry of the Jamaican ‘bayberry’ or ‘pimento’ tree, Pimenta dioica. 18th-century recipes often confusingly refer to it as ‘Jamaican pepper’ not for its taste but because it resembles a round peppercorn, though with a smoother surface. It earned the name ‘allspice’ as its flavour has dominant notes of clove with hints of cinnamon and nutmeg. It is relatively pungent and used in both sweet and savoury recipes.

But back to the oven…

The first time I tried Beeton’s recipe the buns came out more like rock cakes! (Which is fine if you ARE baking rock cakes, but not when you’re expecting soft fluffy buns!) The dough was very dry, brought about perhaps by messing up the yeast quantity – the specified ‘1/2 gill of yeast’ doesn’t equate to the way we buy yeast now – dried in sachets or in a plasticine-like block.

Take 2!

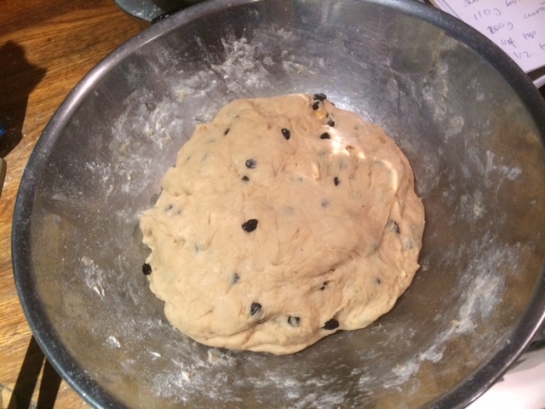

I scoured more cookbooks for clues as to the correct fermenting process. A later, turn-of-the-century Mrs Beeton’s All about cookery features a ‘Buns, Hot Cross’ recipe that made more sense, following the same procedure as the 1861 version but with double the volume of warmed milk, and into which the yeast is added. I took the plunge, and that time was rather pleased with the result – not as soft and bread-like as the (dare I say pappy?!) commercially made varieties, and having a pleasant ‘toothsomeness’ about them. I also prefer the effect of the simple cut-through cross on the top of the bun rather than the flour paste addition – of which I’ve never been a fan.

As everyone’s looking for activities while we’re self-isolating, why not give this a go, and let us know how you get on… and if you’re unsure about the yeast process, I’ve included step by step images below.

Chag Sameach!

Of course this weekend is the Jewish Passover, so if you’ve never tried it have a go at making Matzah brei (there are various spellings) – a simple, traditional breakfast dish of Ashkenazi Jewish origin made from matso and eggs. This is one of those recipes that each family has their variation of (some cook it scrambled for example, some in one piece like a thick pancake which is then sliced) , so a quick online search will find you several to try. A sweet version is sprinkled with sugar.

[This is a revised version of a post first released by Jacqui Newling on March 24th, 2016.]

Hot cross buns, Mrs Beeton’s way

Ingredients

- 450g (2.5 cups) plain flour, sifted

- 100g (scant 1/2 cup) soft brown sugar

- 1/2 cup currants

- 3 tablespoons mixed peel

- 1 teaspoon mixed spice or ground allspice

- pinch salt

- 7g (1 sachet) dried yeast

- 250ml (1 cup) milk, warmed

- 110g butter, melted

- 2 tablespoons sugar, for glaze

Note

Hot cross buns are traditionally served on a Good Friday. This recipe is based on Mrs Beeton's original recipe, published in 1861, which used allspice, and a later turn-of-the-century version which uses the now accepted English-style mixed spice blend.

Print recipe

Print recipe