By 1788 the taking of tea, that very British ritual, was enjoyed universally, even in the poorest households. Although tea was available for sale in Sydney from at least 1792, it was not yet considered a ‘necessary’ and therefore not included in convicts rations for another 30 years. But rather than going without, the early colonists found their own alternative in a native sarsaparilla – testament to their resourcefulness.

We also found a plant which grew about the rocks & amongst the underwood entwined, the leaves, of which boiled made a pleasant drink & was used as Tea by our Ships Company: It has much the taste of Liquorish & serves both for Tea & Sugar & is recommended as a very wholesome drink.

Lieutenant Bradley October 1788.

The convicts’ brew

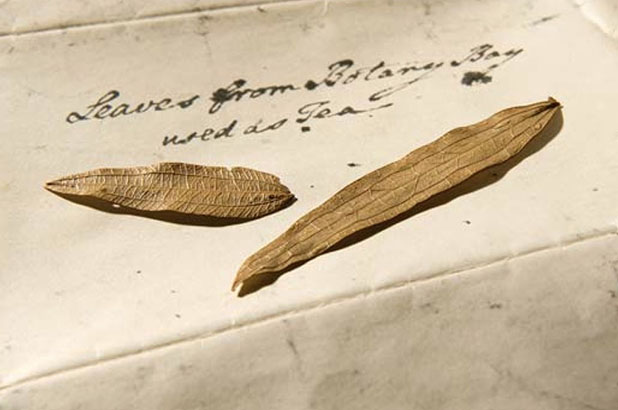

Convicts and lower order marines, neither of whom had access to tea or sugar, found the native alternative very appealing. When boiled and left to steep for several minutes, the leaves from this straggling native sarsaparilla vine, Smilax glyciphylla (the triple-ribbed spearhead shape leaves in the image below), produced a saccharine-sweet licorice-flavoured infusion which earned the name ‘sweet tea’ among the colonists.

When you see this plant growing in the bush, you really get a sense of how much experimentation there must have been to establish which plants might be useful or worth consuming. Smilax glyciphylla was used as a medicinal herb by local Aborigines and the colonists also valued it for its health-giving benefits. The surprising fecundity of female convicts at Port Jackson was attributed to drinking sweet tea and First Fleet naval surgeon Denis Considen claimed that sweet tea would cure scurvy. Perhaps this is why the colonists drank it with such avidity, or possibly they were just happy to have a warm and comforting drink, and partake in a ritual that reminded them of home. Before long, local supplies rapidly dwindled and colonists had to venture further and further afield to find any.

Export quality

Mariner and adventurer John Nichol was suitably impressed with the brew when he visited the colony in 1790 and took a quantity with him on his voyage home. He generously spared some of his stash to treat some fellow ship-mates who were suffering from scurvy, apparently with great success (?!). His ship stopped in China – to pick up a cargo of tea (!) – and, like sending coals to Newcastle, he sold the exotic herb to local Chinese merchants, making a tidy profit on the transaction. Australia’s first export product, perhaps?

Mary Bryant’s tea-leaves

The remarkable Mary Bryant took a quantity of sweet tea leaves on her escape from the colony in 1791, perhaps thinking it would ward off scurvy. Of course we now understand that this wasn’t the case, but the sweet tea may have helped Mary and her party of escapees (her husband William, two small children and seven other convicts) survive the 5237 km journey to Timor, even as a small comfort on the open seas.

Extraordinarily, a few of Mary’s tea-leaves ended up in the possession of renowned author and lawyer, James Boswell, who had taken a benevolent interest in Mary’s courageous attempt at freedom and her consequent criminal case. Two of those leaves are now part of the Collection in the State Library of New South Wales: call number R807 (see image above).

A thwarted effort

Lieutenant Ralph Clark was extremely fond of tea with milk and sugar, according to his journal. But his store of sugar was spent almost before he arrived in New South Wales and his stock of ‘real’ tea was well and truly expended by 1790 when he was transferred for duty on Norfolk Island. Ralph spent days combing bushland in the far reaches of the harbour trying to gather a store of the wild sweet tea leaves to take with him. Sadly for him, all his worldly possessions were lost when the Sirius was wrecked in rough seas on the rocky shores of Norfolk Island, including his cache of sweet tea. It was more than eight months before any new supplies arrived at Norfolk. Ralph and his cohort were reduced to imbibing burnt wheat (as a coffee substitute), so his first sip of tea – Chinese or native – must have been a great relief once the rescue ship arrived with fresh stores.

Post script

Smilax glyciphylla can still be found growing in bushland around Sydney, largely due to bush regeneration initiatives. It’s worth trying if you come across them – two or three leaves will yield a decent pot of tea, boiled for several minutes and allowed to steep for a while – a perfect billy-style brew. Make sure you can identify it correctly – here’s a page from the Royal Botanic Gardens PlantNET site which may help.

And what happened to Mary?

Mary Bryant was eventually pardoned, some six weeks after her original sentence would have expired. Having survived the extraordinary escape to Timor, William and her children died before reaching England. Find out more about Mary Bryant in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.