Purchasing receipts from 1822 tell us that curry powder was one of the many imported goods that the Macarthurs bought from Sydney grocers. By that time, curries were commonplace on finer tables.

In June 1822, Mr Macarthur Esq. ‘bought of V Jacob’ bulk quantities of calico, rice – 195 lbs, sugar – 331 lbs, 25 lbs coffee and 20 lbs of sago, and 5 bottles of curry powder @ 3 shillings each.

Curry for first course

Mrs E’s letter of menus and household advice sent to Maria Macarthur in 1812 suggests curries on no fewer than ten dinner menus – always in the first course, as was the accepted practice of the day. Curry of rabbit was a clear favourite, recommended on four menus; beef and veal appear twice each with two others unspecified. Rice was also recommended to go with each curry.

‘Currey the India Way’

Curries had been known in Britain for some time, as trade contact with India developed via British East India Company activity. The first published curry ‘receipt’, as recipes were then called, was in Hannah Glasse’s first edition of The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy in 1747. It was, in essence, a stew flavoured with basic spices roasted over a fire on a shovel.

To make a Currey the India Way.

Take two fowls or Rabbits, cut them into small Pieces and three of four small onions, peeled and cut very fmall, thirty Pepper Corns, and a large Spoonful of Rice, brown fome small Pieces, and three or four small Onions, peeled and cut very small, thirty Pepper Corns, and a large Spoonful of Rice, brown fome Coriander Seeds over the fire in a clean shovel, and beat them to Powder, take a Tea Spoonful of Salt, and mix all well together with the Meat, pout all together into a Sauce-pan or Stew-pan, with a Pint of Water, let it stew foftly till the Meat is enough, then put in in [sic] a Piece of Frefh Butter, about as big as a large Walnut, fhake it well together, and when it is fmooth and of a fine Thicknefs difh it up, and fend it to Table. If the Sauce be too thick, add a little more Water before it is done, and more Salt if it wants it. You are to obferve the Sauce muft be pretty thick.

Somehow Hannah must have obtained more knowledge of ‘currey’ and curry making over time, refining her receipt in time for the fourth edition published in 1751. Now titled ‘To make a Currey the Indian Way’, the recipe calls for chicken pieces to be cooked ‘Fricafey’ (fricasee) style – that is, blanched then browned in butter before onions, spices and stock are added. A very different mix of spices – salt, Turmerick (sic), Ginger and Pepper ‘beat very fine’ – is used and the dish is finished with lemon juice and cream. Though we might now expect a more complex flavour profile in the spicing, this curry recipe, now 260 years old, is perfectly acceptable for use today.

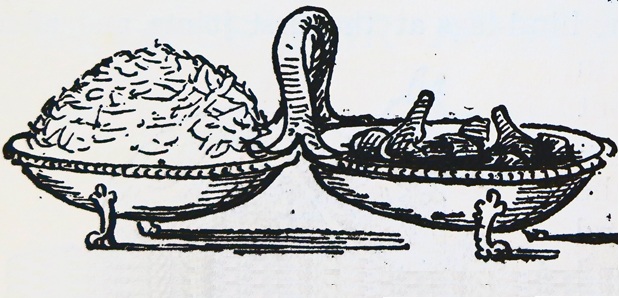

Curry and rice dish illustrated in Mrs Isabella Beeton, The book of household management, Ward, Lock & Co, London, 1890, p1260. Powerhouse Museum Research Library: 641.5942 BEE

‘To boil the Rice’

Invariably curries were served with rice, sometimes ‘answering’ each other in a balanced table arrangement. ‘Well of course’ we might say! But plain boiled rice was a culinary revelation to British cooks it seems.

Glasse’s 1751 edition included instructions ‘To boil the Rice’, which was served ‘dry’ and sent to table ‘in a Difh by itself’ – a novel option for most Britons. Traditionally, rice had been used to thicken soups and stews, or cooked into a pudding, absorbing as much liquid as possible (sweetened milk usually), sometimes cooked to a ‘paste’ or a ‘mammy’. But cooked the ‘Indian’ way, rice grains were meant to be plump yet remain separate and ‘distinct’. For another hundred years, cookery authors went to great lengths to describe how this effect could be achieved, which some of us have only mastered with the advent of the electric rice-cooker.

From exotic to commonplace

In the 1700s India herself was exotic and mysterious, experienced only by intrepid traders and gallant soldiers. But by the time of Victoria’s reign, India was fast becoming engulfed by the British colonial Empire, and curries and Anglo-Indian creations (or adaptations), such as rice kedgeree and mulligatawny soup, chutneys and piccalilli (mustard pickles), had become commonplace on British and, by natural progression, Australian tables. Rather than being revered, curries were relegated to ‘Cold meat cookery’ (aka leftovers) sections in cookbooks, often made to ‘authentic’ recipes with commercial curry pastes and powders.

Mulligatawny

| Region | Indian |

Ingredients

- 1 large onion (finely sliced)

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 500g chicken thigh fillets (trimmed of visible fat)

- 1 tablespoon Indian-style curry powder (eg Madras, or see Edward Abbott's curry powder on this blog)

- 2 tablespoons rice flour

- 1 large Granny Smith apple (peeled, cored and seeds removed, and grated)

- 1.5l (6 cups) chicken stock

- 1 cup cooked basmati rice (cook 1/3 cup of rice the day before and refrigerate)

- 1/4 cup coconut milk (optional)

- juice of 1 lemon

- cayenne pepper (or chilli powder), to taste

- chopped mint or parsley, and natural yoghurt (optional), to serve

Note

Mulligatawny is a curried soup. Rice was originally served on the side but, over time, ended up as an ingredient in the soup. Coconut cream can be added for a richer version.

Serves 4

Directions

| In a large saucepan sauté the onion in the butter over medium heat for 10–15 minutes until nicely browned. Be careful not to burn the butter. Add the chicken and cook gently, turning occasionally until the chicken starts to brown. | |

| Sprinkle the curry powder and rice flour over the onion and chicken. Stir briefly, then add the apple and chicken stock. Simmer for 20 minutes or until the chicken is cooked and the apple is soft, stirring occasionally to prevent the soup from sticking to the base of the pan. Remove the chicken fillets and shred the meat. | |

| Add the rice and cook gently for 10 minutes so that the rice absorbs some of the flavours. | |

| Return the chicken to the pan and add the coconut cream, if using, along with the lemon juice and cayenne pepper to taste. Add 125 ml (1/2 cup) or more of water for the desired consistency, and cook over low heat for a few more minutes. Ladle the soup into shallow bowls and serve with the herbs and a dollop of yoghurt, if using. | |

See also: Curry chemistry for the Kedgeree recipe.

Sources

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy. First edition 1747 & fourth edition 1751. Accessed via Gale, Eighteenth Century Collection Online

Print recipe

Print recipe