With the temperature dipping out at Rouse Hill we’re all rugging up and have started lighting the fire in the mornings to take the chill out of the office. Which naturally brings us to a discussion about ice, and a strawberry blancmange for dessert!

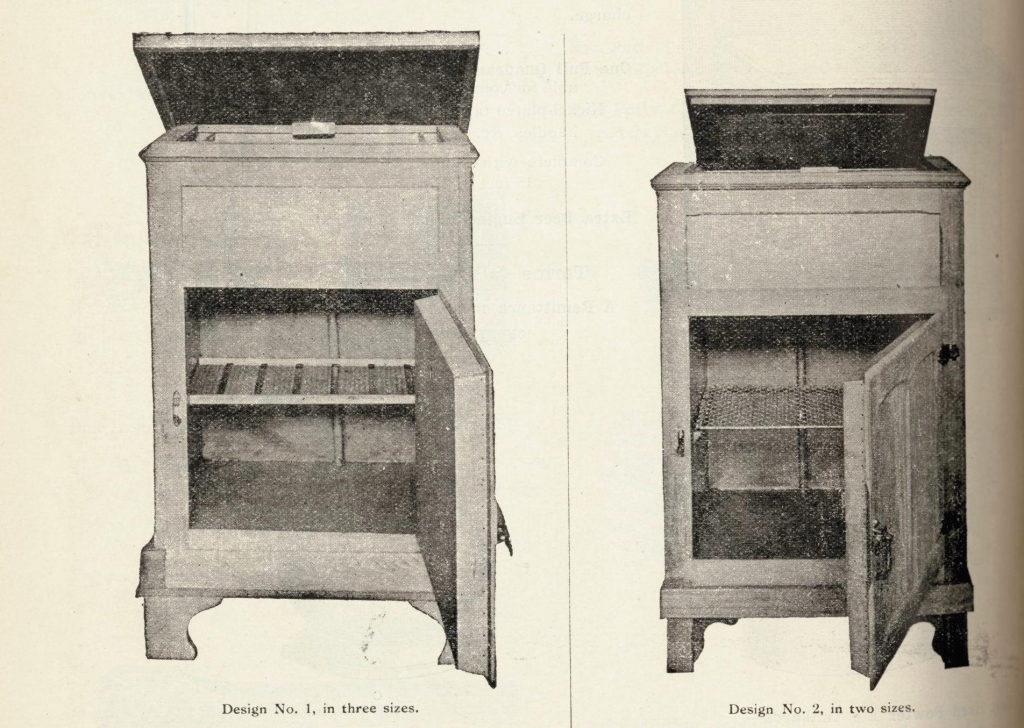

I’ve talked before about the first imported ice arriving in Sydney in 1839 (hooray! Cocktails!) and Jacqui’s discussed ice deliveries at Susannah Place – with local kids clamoring for the ice chips. By the late 1800s ice deliveries were routine to many houses, and certainly by the early 1900s it was common as ice chests (also called ice safes) became a domestic fixture. Closer to Rouse Hill, ice works were established at both Richmond and Windsor. Catalogues published by retail emporium par excellance Anthony Hordern & Sons illustrate ‘Chilcott refrigerators’, as manufactured at their Redfern factory. Of various sizes and containing one to multiple compartments these were designated for home or commercial use. A typical feature of these 1907 examples, retailed by Anthony Hordern & Sons, is the top-loaded ice compartment, accessed by a lid and with wire shelving:

Chilcott refrigerator: Design no.1 and Design no.2, advertised in Anthony Hordern and Sons’ household catalogue, Anthony Hordern & Sons, Sydney, July 1907. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TC658.871 HOR/2

Chilcott refrigerator Design no.5 Size G, advertised in Anthony Hordern and Sons’ household catalogue, Anthony Hordern & Sons, Sydney, July 1907. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TC658.871 HOR/2

The ice should be wrapped in a piece of clean sacking or cloth, as this helps to protect it from the effects of the rush of heated air when the lid is opened.

Harmwsorth’s Household Encyclopaedia , London, 1926

Down the stairs

In the cellar at Rouse Hill house is a large and quite unusual – and much earlier – chest. Held within a large wooden case is the expected zinc box, though here it is cylindrical, not the more familiar rectangular shape. It is also a double cabinet, with both inner and outer doors for extra insulation. Placed in the top compartment the ice block sent cold air downwards. As it slowly melted iced water dripped down and around the curved surface and was collected at the base in a drip tray (a larger tray has been placed under the whole box to catch any leaks). An interesting detail is the oak graining on both the outer panels and inner doors. With no manufacturers details or stamp, it’s thought to date to between 1860 and 1880.

Ice chest in the cellar at Rouse Hill with outer doors open revealing the insulated compartment within. Sydney Living Musuems R82/22

Ice chest at Rouse Hill fully open to reveal the circular compartment within, and with the lid to the ice compartment open. Sydney Living Museums R82/22

Gerald Terry, the house’s last permanent occupant, recalled 2 ice chests being kept in the house. One – this chest – was located in the first cellar room, where foodstuffs were stored (the second being a wine cellar). With an eye to practicality the second was kept in the back hall, to save running up and down the stairs. Given that the cellar stairs aren’t the most ‘ergonomic’ in the world it must have been a trial lugging fresh blocks of ice down them each week. Knowing just how hot it can get at Rouse Hill in high summer, an ice chest must have been a highly valued acquisition. Having access to ice made all sorts of exotic dishes possible, as well as preserving fresh food such as meats for a few extra days. A cover-less book in the Rouse Hill collection, originally from the Terry’s nearby Box Hill property and inscribed ‘N[ina] B[eatrice] Terry’ [1] has this advice for making ice cream:

How to freeze without a machine

Ice and coarse saltMode – Break up the ice into small pieces, and put it into the outer vessel in alternate layers with the salt – say for instance a bucket; put the mixture [what it is you want to freeze] into a billycan or anything that would do as well; cover it well with the ice and salt; keep stirring and shaking it until the mixture is set; if wanted for a cream, it will then be ready for use, but if wanted for iced puddings you must turn it into a mould and place it back into the ice, but do not stir it any more; when it is required turn it out onto a glass dish. Of course, where people have ice cream machines it is very simple.

The term ‘iced’, often seen in recipe books, refers to a recipe made with the assistance of ice for chilling or setting.

Ding dong dell, dessert is down the well!

The oral histories of Rouse Hill House also discuss an alternative to the icebox that we also know from Meroogal. Miriam Hamilton remembers her grandmother Nina Terry (nee Rouse) lowering a dessert mould into the cistern to where it just rested on the cold water, outside the kitchen wing in order to set a pink blancmange when the ice had run out. Nina was taught to cook by Kate Joyce, who worked for the family for 50 years. Caroline Thornton describes her grandmother’s hearty cooking:

These days hostesses go to great lengths to make their dishes ‘look’ appetizing and to create exotic dishes. Granny did neither of these things. She used the materials which she had and brought out their flavour in a most delicious way.” [2]

In the Rouse Hill collection is a cover-less cookbook with a recipe for a pink strawberry blancmange. Over the years it has collected the loose board of a Mrs Maclurcan’s cookbook, but is actually ‘Warne’s every-day cookery’, possibly dated 1872 [3]. ‘Isinglass’ is used as an alternative to gelatine, and is made from the swim bladder of a fish such as cod or sturgeon. While simply adding a few drops of red cochineal colouring to a basic blancmange mix would give a pink colour, this recipe has the flavour of strawberries:

Notes

[1] Nina Rouse (1875-1968) married George Terry of adjacent Box Hill in 1895. They lived there till George’s bankruptcy forced them to move in with Nina’s father Edwin Stephen Rouse (1849-1931) at Rouse Hill in 1824, following the death of her mother Bessie (1843-1924).

[2] Caroline Thornton, Rouse Hill House and the Rouses, the author, Nedlands W.A., 1988. p180.

[3] Mary Jewry, Warne’s every day Cookey, containing one thousand eight hundred and fifty eight distinct receipts. London, F. Warne, [1872?].