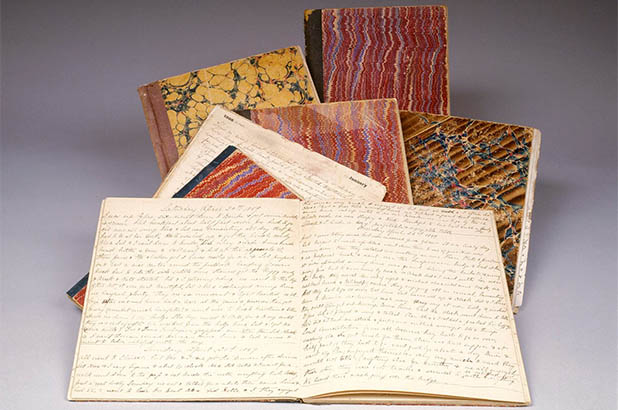

Kennina Fanny McKenzie Thorburn, or as we know her, Auntie Tottie or Tot, was the youngest of the eight Thorburn children. Thankfully for us, Tottie kept diaries and the ones written between 1888 and 1896 provide us with a wonderful record of daily life in the late nineteenth century. They are rich with references to food and cooking, and reading them, you really get the rhythm of the daily domestic rituals of a young woman whose life centered around the home.

June Wallace described her great aunt Tottie as

very lively and sparkling…she had the very best of dispositions; I found a song and a smile in her voice… attractive in her youth, and indeed she was charming in old age.

Tottie spent many years caring for her elderly grandfather, and when he died, she returned to live with her mother and sisters at Meroogal in 1892. There is much to discover about Tottie’s life and her diaries but of course I’m interested in what they reveal about food in her times. Many of the family’s most treasured recipes relate to Tottie’s time at Meroogal, and she was responsible for much of the cooking.

All in a day’s work

Tottie and her sisters were not afraid of hard work, often rising at 4am to get their household chores done – cleaning, washing, baking or making jams or preserves. On May 24, 1888, Tottie recorded, ‘Making jam from six o’clock in the morning until six at night’. Her repertoire was wide-ranging, drawing on seasonal fruit from the garden and local orchards. Melon jam was clearly a favourite, sometimes jazzed up with ginger, gooseberries or pineapple; quinces, apples, gooseberries, oranges, tomatoes, peaches, mandarins and even grapes found their way into jars as jams, jellies and preserved fruit for gifts and for the pantry. You can imagine disappointment mixed with resignation in her mind as she recorded one Saturday in October 1889, ‘Apricots a failure’. Given that apricots are summer fruit, the forming crop must have been looking pretty sad.

The Thorburn family at Meroogal, Nowra, in 1891: standing at the back, left to right: Kate Thorburn, Mary Susan Thorburn, Belle Thorburn and Tom Thorburn; seated front, left to right: Robert Taylor Thorburn, Bruce Stafford, Georgie Thorburn, Tot Thorburn and their mother Mrs Jessie Catherine Thorburn. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection, Historic Houses Trust

Breakfast, dinner and tea

The wood-stove in the kitchen was the ‘pivot’ of the daily routine and it was the sole source for any hot water for the household. ‘The Younger’ stove (below), made by Fletcher & Co, a Sydney foundry, remains in the kitchen and is a handsome piece; it sports an embossed emblem of a crown flanked by a kangaroo and an emu and imprinted below, ‘Advance Australia’, indicating that it dates from around 1908 – or perhaps our readers might be able to tell us more accurately? In summertime it would be lit in the very early morning so that any baking could be completed before the heat of the day. If all the chores were done, breakfast could be quite leisurely, around 9am, but the fire would stay lit until ‘dinner’, the main meal taken at noon, was prepared. The evening meal or ‘tea’ was a much lighter affair. Rather than entertain at dinner, visitors would be received on a regular basis, for a catered ‘At Home’ tea, which we’ll talk more about later this month.

The ‘roogal bounty

Tottie’s diaries give us a good picture of domestic fare in the late 1800s. In addition to all the jams and preserves, Tot made a myriad of biscuits, cakes, pies, tarts and scones (batches of which were made several times a week). She was renowned for the lemon biscuits that she was ‘constantly’ baking in the wood-stove and for wedding cakes which her niece Helen would ice and decorate. Sweet treats outweighed savoury dishes immeasurably, but her diaries mention fish and oysters, beef steak, tongue, homemade cheese and soda breads. Feathered game is recorded only in the early years – cockatoo, pigeon and parrots, and the occasional fowl. The family kept chooks, enjoying a good supply of eggs and George, a Chinese immigrant who tended the orchard and established a kitchen garden, kept the household well stocked with fresh produce. George was with the family for 25 years, returning to his homeland quite regularly, returning with oriental gifts for the family.

Although the house now only occupies a suburban block, Meroogal still has productive fruit trees. When I visited today tiny apples were beginning to form on the tree beyond the verandah, the last of the pretty pink berries from the lilli pilli tree dotted the pathway behind the kitchen and we’re still enjoying the grapefruit marmalade from last year’s bounty (recipe below).

Grapefruit and ginger marmalade

Ingredients

- 1kg grapefruits (about three)

- 2 lemons

- 1kg caster sugar

- 100g crystallised ginger

Note

Note: this recipe needs to be started the day before, to soak the fruit. Soaking helps to prevent pieces of fruit from rising in the jar, producing an uneven mix.

If you don’t have crystallised ginger, try finely chopping or grating a thumb-sized knob of fresh ginger, skin and all, and boiling it in water to transfer the flavour. You could also use 1 or 2 tablespoons of bottled minced ginger – stir it into hot water and allow it to infuse for an hour or two. Strain then discard the ginger and use the flavoured water in the recipe.

Directions

| Peel the rind from the grapefruits and lemons. Shred the rind. Trim the layer of pith from the flesh and put to one side. Slice and chop the flesh, removing the seeds and keeping them to one side with the pith. Wrap the reserved pith and seeds in a muslin ball and tie securely with string – they contain pectin and will help the marmalade set, but will be removed later in the cooling process. | |

| Place the chopped flesh, shredded rind and muslin bundle into 1.5 litres of water in a large, heavy-based saucepan and soak overnight. | |

| Next day, bring the mixture to a gentle boil and cook for about 15 minutes or until the rind is tender. Reduce the heat and add the sugar, stirring constantly until the sugar has dissolved. | |

| Add the crystallised ginger and increase the heat to medium. Boil for about an hour or until the jam reaches its ‘gel point’. Supervise well – make sure the mixture doesn't bubble up and boil over, and stir occasionally to ensure the mixture doesn't burn or stick to the pan. You will have to stir almost constantly as the mix nears completion. Remove the muslin bag and discard. | |

| Transfer the jam to hot sterilised jars, and secure lids while the jam is still hot. Enjoy! | |

Sources and notes

Janet K. Ramsay, ‘The Women of Meroogal’, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 1988.

J. Wallace, ‘Memories of Four Great Aunts’, unpublished manuscript, 1986, held by Historic Houses Trust of NSW.

Special thanks to our volunteer researcher Bethany Leyshan for her contribution in this project.

Print recipe

Print recipe