This April Fools Day I’m departing from tradition and not telling a whopper, but I’m still talking about fools – the dessert that is.

Soft, pale, creamy untroubled, the English fruit fool is the most frail and insubstantial of English Summer dishes.

Elizabeth David, ‘A taste of the sun’

In essence, a fool is a dessert made by folding pureed fruit through cream, or sometimes custard. Yes, it really is that simple. The delight in a really good fool is therefore in the quality of its ingredients and its presentation.

The original Elizabethan recipes for fools (or ‘fooles’) involve adding egg to cream, to make a custard-like mix through which fruit was folded with pounded (i.e. fine) sugar. If you think of the richness of Elizabethan food, and the very high value on imported spices like nutmeg and cinnamon, you quickly see the status of these dishes. The original concept evolved and become simpler over the following centuries. Looking through books by Beeton, Acton and Raffald, there are several recipes for what we would now call fools, though many go by the simpler name ‘creams’. They are part of a range of related recipes that include tansey and blancmange. The great Elizabeth David wrote of the evolution of the recipe:

Two hundred years ago it was those recipes listed under the heading of creams which were more like the fruit fools of today. Evidently at some stage, it came to be appreciated that the eggs and the extra flavourings were unnecessary, that they even distort the fresh flavour of the fruit. This is especially true of berry fruits and apricots. Gradually the delicacy now regarded as the traditional English fruit fool came to be appreciated as a puree of fruit, plus sugar, fresh thick cream, and nothing more. [1]

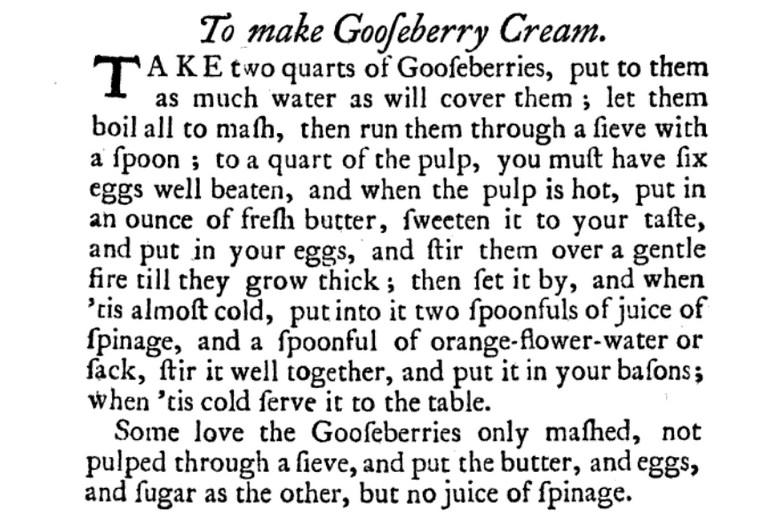

Almost 250 years earlier, Eliza Smith’s The compleat housewife: or, Accomplished gentlewoman’s companion [2] gave a recipe for a classic fool which she called, simply, a ‘Gooseberry cream’:

Gooseberry cream recipe from The Compleat Housewife, 1839 edition. Source: Google Books

Mmmm, ‘juice of spinage’. You just don’t see it any more.

An evolving recipe

Jump forward to the Regency and in her 1806 ‘The Compleat Houfewife” Eliza Rundell gives 3 recipes that sit at the point where the recipe is becoming simpler, with the eggs typically omitted and in its recognisable modern form. From here on, as David notes, they’re far more often termed ‘creams’ – though those made with gooseberries, rhubarb and sometimes apple are always, it seems, known as a Fool. Just to mess up my terminology though, in Rundell’s recipe for an ‘orange fool’ – which is also in Smiths earlier work, though called a ‘cream’ [3] – egg is still included:

Orange Fool

Mix the [strained] juice of three Seville oranges, three eggs well beaten, a pint of cream, a little nutmeg and cinnamon, and sweeten it to taste. Set the whole over a slow fire, and stir till it becomes as thick as good melted butter, but it must not be boiled [or the egg would set hard]; then pour it into a dish for eating cold. [4]

In her accompanying recipe for a gooseberry fool however, Rundell has an either/or approach to the egg: “…have ready a sufficient quantity of new milk [ie unseperated from the cream], and a tea cup of raw cream, boiled together, or an egg instead of the latter.” A “sufficient quantity”? Yep, there’s that frustrating lack of quantities again. For an apple fool her recipe was effectively the same: “stew apples… and then peel and pulp them. Prepare the milk, &c. and mix as before” (though again she frustratingly omits the quantity of fruit…)

A century later, Cassell’s 1909 ‘Household cookery’ gives several recipes for creams, yet retains the term ‘fool’ for the big three: gooseberries, rhubarb and apple:

Gooseberry fool:

Take the tops and stalks from a pound of green gooseberries, and boil them with three quarters of a pound of sugar and a gill of water. When quite soft, press them through a coarse sieve and mix with them, very gradually , a pint of milk; or cream, if a richer dish is required. Serve when cold. This old-fashioned dish is wholesome and inexpensive, and, when well-made, very agreeable. Time, about twenty minutes. [5]

Likewise, the recipe for ‘rhubarb fool’, where the author adds: “…although a departure from the usual custom, we think this dish is much richer if the fruit be allowed to cool before the cream is added; and it is certainly nicer if if the cream be whipped; the bulk is also increased thereby.”

For me a fool today is simply pureed fruit folded evenly through cream, though using a tart fruit works best as its gives the dish a contrast of flavours. This is why gooseberries, raspberries, apples and citrus work especially well. An important note is that you need to be careful preparing your fruit: strawberries for example should be pressed through a sieve uncooked, or their lovely colour will be lost.

If you look at modern recipes you’ll often see mascarpone, even tangy Greek yoghurt being added or substituted for t cream. Here’s one example.

Cook’s tips, and my favourite fool

I use whipping – also called ‘pouring’ – cream (not pre-whipped or thickened), as I think this gives the best result in terms of appearance and texture, and really with a recipe this simple its worth a bit of effort. Avoid double cream – its way too thick even when the fruit is added. Plus it’s cheating. I usually go by proportion when making a fool, about 1/4 fruit to 3/4 cream. Any more and you risk a too runny fool, and having the fruit overwhelm the cream, and be careful about adding very liquid puree as this can make the fool separate in the glass.

A particular favourite of mine is a custard apple fool; for that mash the flesh of the custard apple with a fork then pass through a sieve to puree, and quickly mix with a splash of lime juice to stop it going brown. Turn through the cream quickly as this will also stop the fruit browning as it is exposed to the air.

Fools and creams are best served individually, in fine glasses, though you could use a decorative porcelain bowl or glass comport.

A short cut?

Some of you are probably thinking if you could fold a good (home-made) jam through cream to make a fool. Several recipes I’ve seen, even early 19th century, say to fold in the ‘preserves’, namely jam or a puree made from preserved fruits, though a thick jam would have trouble blending and you may need to warm it slightly and work it with a spoon beforehand. You could also use ready-made pureed fruit (admit it, you were already thinking ‘baby food’ weren’t you). The catch is that a raspberry or strawberry jam will still have the seeds, so you will still have to use a fine mesh sieve to achieve a completely smooth cream.

A Raspberry Fool

A raspberry fool is especially easy to make, and has the lovely contrast between the sweetness of the cream and the tartness of the raspberries. The only real technique is to press the raspberries through a fine wire mesh sieve. If you were using custard apple you could use a more open sieve or even a strainer, or simply mash the fruit in a bowl with a fork.

Using Smith as a guide Ive also tried making a fool using an egg, whisking it in to the cream using a bain-marie to heat the mix, but find it won’t whip later and is far more akin to a cream consistency – as the name suggests. It does give the dish a subtle custard-taste, and you can sip it or dip a biscuit in. Definitely best served in a glass.

Ingredients: I use a cup and a half of raspberries (frozen is fine), 3 tablespoons of fine sugar, and 600 mls of cream.

Method: Start by pureeing the raspberries:

Mashing the raspberries through a fine sieve. (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Here you can see the fine puree coming through the sieve. It has the consistency of olive oil and a wonderful vivid colour:

The smooth raspberry puree. (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

A smooth raspberry puree. (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

What you’ll be left with is a coarse residue full of seeds – discard this:

Coarse seed pulp left after mashing the raspberries. (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Reserving a few tablespoons, turn the puree into into the whipped cream along with the sugar, and fold through till even. It will go a nice pale pink colour.

Turn carefully into a large compote, or individual glasses. Place into the refrigerator, and chill. When ready to serve, drizzle a little of the reserved puree on top of each. For a pretty effect, as Mrs B would say, layer the puree and the cream so crimson stripes show through the glass. If you were feeling really ambitious, layer white and pink cream with the puree.

Serve with crunchy wafers (and champagne).

Raspberry fool ready to serve. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Happy April Fools Day!

Notes

[1] Elizabeth David, A Taste of the Sun. First published Penguin, London, 1969.

[2] 9th edition, London, 1739. Online at Google books

[3] Smith’s recipe: “To make Orange Cream – Take a pint of the juice of Sevil oranges, put to it the yolks of six eggs, the whites of four; beat the eggs very well, and strain them and the juice together; add to it a pound of double-refin’d sugar beaten and sifted ; set all these together on a soft fire, and put the peel of half an orange into it, keep it stirring all the while, and when ’tis almost ready to boil, take out the orange-peel, and pour out the cream into Glaffes or China dishes.”

[4] Eliza Rundell, ‘A new system of domestic cookery’, London, John Murray, 1816 (6th edition). Reprinted with a preface by Janet Morgan, London, Persephone Books, 2009

[5] Lizzie Heritage, ‘Cassell’s Guide to Household Cookery’, Cassell & Co., Melbourne, 1909. p1123