If I was going to do a ‘Julie and Julia’, the book I’d want to work through is Modern cookery for private families, first published 1845 by Eliza Acton’s (1799-1859). It is written with eloquence and grace, and with practical descriptions of mid-1800s English cookery.

It was sold in bookshops in the colony, and was the ‘go to’ cook book for prospector William Howitt, in the Ballarat goldfields in 1853.

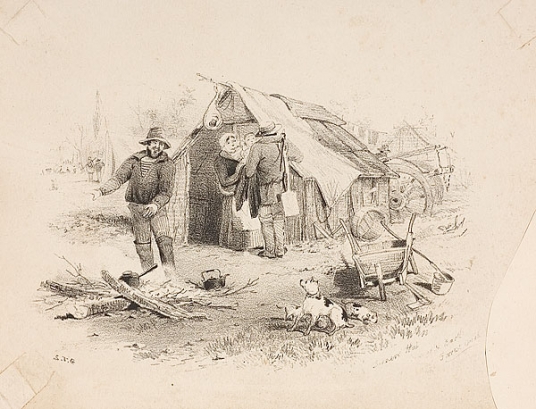

‘Zealous Gold Diggers, Bendigo, 1852’. S.T.Gill National Library Australia Call Number PIC S143

A colonial presence

We know Acton’s Modern Cookery was used in the Australian colonies – it was advertised for sale in bookshops and recorded on household bankruptcy inventories in the 1850s. But the author was bound to be surprised that it found its way onto the Ballarat goldfields, where fossicker William Howitt took great delight in trying to reproduce her dishes with somewhat compromised resources. Howitt was somewhat biased in his choice of cookbook. He was a friend of Eliza’s, and brought a copy with him to Australia. He wrote her a letter about his experiences at the diggings, providing wonderful descriptions of daily fare and how he adapted English recipes to local ingredients. The letter has been transcribed and published into a small book titled ‘First catch your kangaroo’ [2], a play on the old English adage, ‘first catch your hare’ (which has its own controversies in culinary circles but I’ll leave that for another blogger to debate).

S. T. Gill, Diggers hut, canvas and bark, Forrest Creek 1852, ink and paper, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 2005

Producing wonders

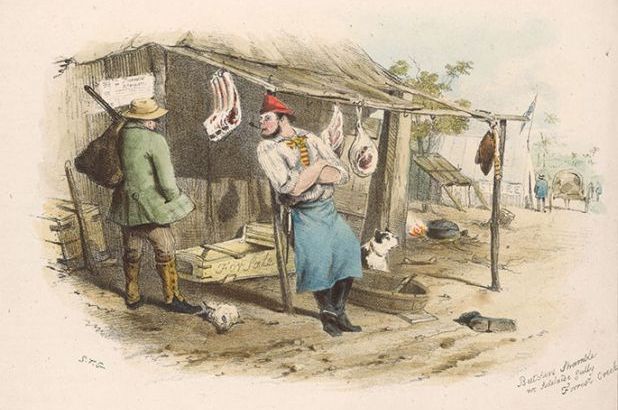

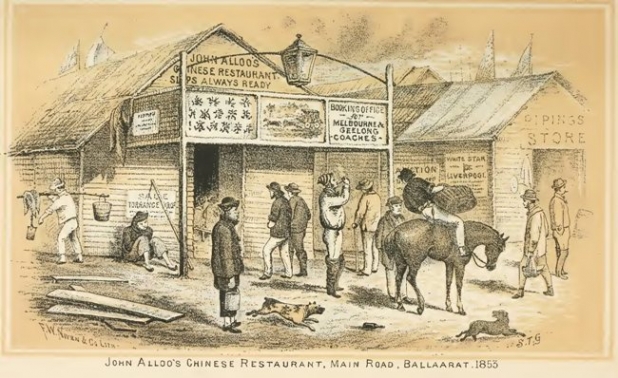

William’s letter explains that milk and butter were luxuries, but that many families kept a milch-goat and fowls so that eggs were on hand. Suet, bacon or pork fat was used in place of butter; people kept stores of dried peas and legumes, jam, sago, dried fruit, sugar and spices, and according to William you could ‘produce wonders out of them’. He waxed lyrical about plum and suet puddings, apple-puddings from dried apples and jam roly poly style desserts. Potatoes were cheap and meat could be bought from tent-stalls, as the S. T Gill ‘Butcher’s Shambles’ illustrates (at the top of this post), and Chinese gardeners kept a ready supply of fresh vegetables and merchant-traders supplied dry-goods and tea. There was a Chinese restaurant at the diggings (shown above), though it is likely it sold western style food rather than oriental.

‘John Alloo’s Chinese restaurant, Main Road, Ballaarat, 1853’ / F.W. Niven & Co.; S.T.Gill. National Library Australia NK3770/8.

Damper and tea

Damper, much improved with a little bicarb soda and tartaric acid (ie baking powder) was gold miner’s staple – a ‘bushie’s’ version of soda bread without the buttermilk. The Bicarb soda was boon – eliminating the need for yeast or a sourdough culture, and needed no time waiting for the loaf to prove. William Howitt was pretty pleased with the result:

We make famous bread, however, far superior to any that the bakers turn out … No bread can rise better than this does, it often lifts off the lid on the camp oven to look about it, it is so much puffed up with itself

Another variation was ‘Leather-Jackets’ – made the same way but fairly flat and baked on a frypan – perhaps a bit like a think pizza crust, hence the ‘leather jacket’ exterior. Fry the dough in fat and they became ‘fat-cakes’.

Invariably whichever of these was on the menu de jour, they were washed down with Bush tea – drunk from ‘panikins’ without milk or sugar, but Howitt assures Eliza that

One gets to like it very well here. The true bush way to make it is to put the tea & sugar, strong brown sugar, one gets to like none else here, into the tea-kettle and boil them, yes, boil them up together. the people here make it very sweet. It is in fact, tea syrup.

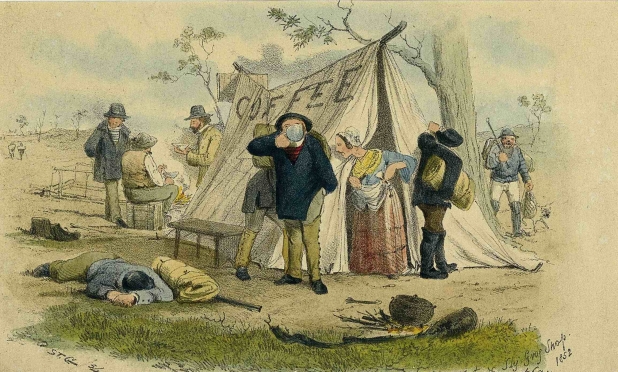

We presume that it was actually tea in Howitt’s panikin – S.T. Gill’s image below suggests this may not always be the case for less reputable fossikers!

S. T. Gill, Coffee tent and sly grog shop. Diggers breakfast 1852. 1854, paper lithograph, hand-coloured in watercolour, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 1986

An unrequited love

Eliza Acton aspired to be a poet, but was persuaded by her publisher to compile a cookbook. Her love for poetic language, and an obvious interest in culinary arts, resulted in a thoughtful and eloquently composed text – and the odd poetic recipe, including Mother Eve’s pudding

References:

[1] Acton, Eliza. Modern cookery for private families. 1855 facsimile edition with introduction by Elizabeth Ray. Southover Press, London.

[2] First catch your kangaroo. A letter about food written from the Bendigo goldfields in 1853 / by William Howitt to Eliza Acton ; introduction by Valmai Hankel ; foreword by Michael Symons. Adelaide : Libraries Board of South Australia, 1990.